How does visual poetry make space for multiplicity?

£45.00 *

£45.00 *

£45.00 *

£45.00 *

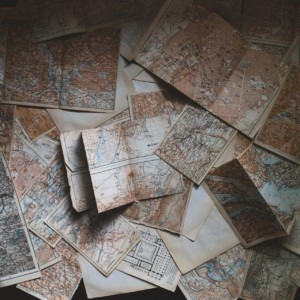

How does visual poetry make space for multiplicity?

£45.00 *

£45.00 *

How do we translate the pain of losing love into poetry?

£210.00 *

£210.00 *

Fissile material; experiment with scientific stanzas and supercharge your poetic skills.

£126.00 *

£126.00 *

Alternate art; busting open the poem to embrace new and experimental forms.

The 2022 Ginkgo Prize Ecopoetry Anthology contains all the winning and highly commended poems from this year’s awards, judged by renowned poet ecopoet and memoirist Seán Hewitt, and ecopoet, writer, and editor Karen McCarthy Woolf.

The winning poets were Anthony Lawrence, Cath Drake, Yvonne Reddick and the AONB Best Poem of UK Landscape was written by David Canning.

Here’s Laura Scott on her upcoming course, Poems & Houses; House & home; poetics of our storied buildings. My house and the ghost of a doorway In my house there’s the ghost of a doorway. I can’t remember when I first noticed it, but I do remember the gentle shock of running my hand over…

Read More

Here’s Mario Petrucci on his upcoming course, Science & Poetry: The Laboratory of Verse; Fissile material; experiment with scientific stanzas and supercharge your poetic skills. Science as a metaphor As someone versed in quantum physics, I’m fascinated by metaphor, the way everything (as in the quantum world) can become everything else. That’s the engine-room of my…

Read More

Are you a published writer? Do you love nature writing and want to inspire audiences to connect with the National Landscapes of England? Do you have a meaningful connection to one of these six regions: Nature Calling is a ground-breaking national project, that will commission an exceptional, diverse range of artists to explore and celebrate…

Read More

Nicola Healey reads the new poetry collection by Peter Wallis: Half Other, ‘a reminder of the significance of lateral relations in our lives’ whole’. ‘I was not born alone’: Twinhood and Illness Peter Wallis’s first full collection, Half Other, takes inspiration from his life as a twin, focusing on the lengthy ill health and hospital…

Read More

In addition to our Summer programme this year, we are running a series of exciting courses tutored by fresh voices from The New Poets Collective. Have a look at the below quick guide to this fantastic line up and make sure you book your place quickly to avoid disappointment! In-Person Courses Poems as Constellations with…

Read More