I Remember by Joe Brainard is the first poem I think about when I think about list poems. It’s a book-length poem consisting of a series of statements, all of which begin with the refrain ‘I remember’.

Here’s an example:

I remember planning to tear page 48 out of every book I read from the Boston Library, but soon losing an interest.

I remember Bickford’s.

I remember the day Marilyn Monroe died.

I remember the first time I met Frank O’Hara. He was walking down Second Avenue. It was a cool early Spring evening but he was wearing only a white shirt with the sleeves rolled up to his elbows. And blue jeans. And moccasins. I remember that he seemed very sissy to me. Very theatrical. Decadent. I remember that I liked him immediately.

Brainard’s poem goes on for around 130 pages. The scale of the poem could become tedious if it weren’t for the swerves in line length, the unexpected order of the statements, and the variations in tone. As the above example begins to illustrate, there are massive changes in pace from short, simple sentences to long, complex passages. The element of surprise is the crux of any list poem; Brainard’s poem is fabulously funny one moment and then terribly sad the next. In the words of poet and critic Larry Fagin, a list poem ‘must have a poetic bump in the road’.

I’m not sure if we could say that Brainard invented the ‘statement to be filled in’ list poem. Perhaps it derives from Whitman or Ginsberg but, in any case, it certainly is a form that is commonly utilised. Close in spirit to Brainard’s poem are Georges Perec’s homage I Remember, Perec’s fellow Oulipian Jacques Bens’ J’ai Oublié (which means ‘I’ve forgotten’ in French), and poems such as Emily Berry’s ‘Some Fears’, which uses prose as its form.

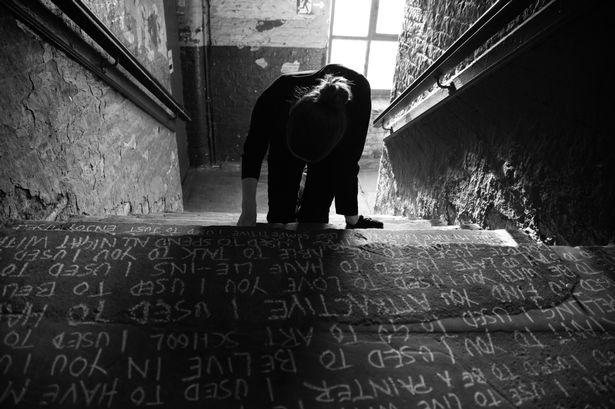

In another medium, artist Sarah Sanders’ live writing list piece, I Used To, does not have an arbitrary amount of lines like the poems listed above. Sanders limits her ‘I used to’ phrases to the steps available within the buildings in which the live writing takes place.

The list poem, then, is known as much for its power to work within, and examine, constraints as it is for its ability to convey a sense of excess. List poems can also be extremely comical, for instance Ron Padgett’s sonnet ‘Nothing In That Drawer’, which consists of fourteen lines, all of which say: ‘Nothing in that drawer’. Try saying it out loud fourteen times and you will start to see the possibilities – what at first glance look like straightforward repetition can become a mantra or be read in fourteen different voices.

Just as the sonnet is a great form for the list (see Shakespeare’s ‘Sonnet 66’ or John Clare’s sonnets for more), other poets have set themselves different constraints. Matthew Welton’s complex, but not complicated, poem ‘Two Hands’ uses the clock and its twelve numbers as titles for twelve stanzas, each of which builds up in line length as a sort of hybrid sestina. Here’s the beginning:

Noon

The dizzy girl walked quickly down the beach

1.05

The roads were slow. The fields were full of fruit.

The smiling boy drove up beside the beach

There are many other dynamics to the list poem which I had planned on writing about through poems such as Benjamin Zephaniah’s ‘Vegan Delight’, Harryette Mullen’s ‘We Are Not Responsible’, Ceri Buck’s ‘Characters In Their Thousands’ and Tom Jenks’s ’99 Names for Small Dogs’. But for now, as the saying goes: ‘the list goes on’. If you want to discover more, you’ll have to come on the course to find out how these and other poems might influence your own writing.

Book here for James Davies’ one-day workshop This Goes There, That Comes After: List Poems, running as part of our Spring Term 2020.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.