We’ve asked the five poets shortlisted for this year’s Forward Prize for Best First Collection to write about the process behind their award-nominated work. Over the weeks leading up to the award ceremony on 21st September, look out for ‘How I Did It’ articles from Maria Apichella, Nick Makoha, Eric Langley, Richard Georges and Ocean Vuong. This week, Richard Georges discusses his poem ‘Griot’.

Most of the poems in Make Us All Islands began as part of the creative component of my doctoral thesis at Sussex. While the collection is focused on the sea in its assorted manifestations – vault of many histories, graveyard for genocides, transformative portal – one of my parallel preoccupations while writing was to commit the British Virgin Islands and its underwritten landscape to the page. I realised rather quickly that this sort of endeavour can quickly become a burden and therefore many of the poems went through torturously obsessive revisions. One poem that avoided this process is ‘Griot’, the first poem of the book, which more closely follows my usual writing practice.

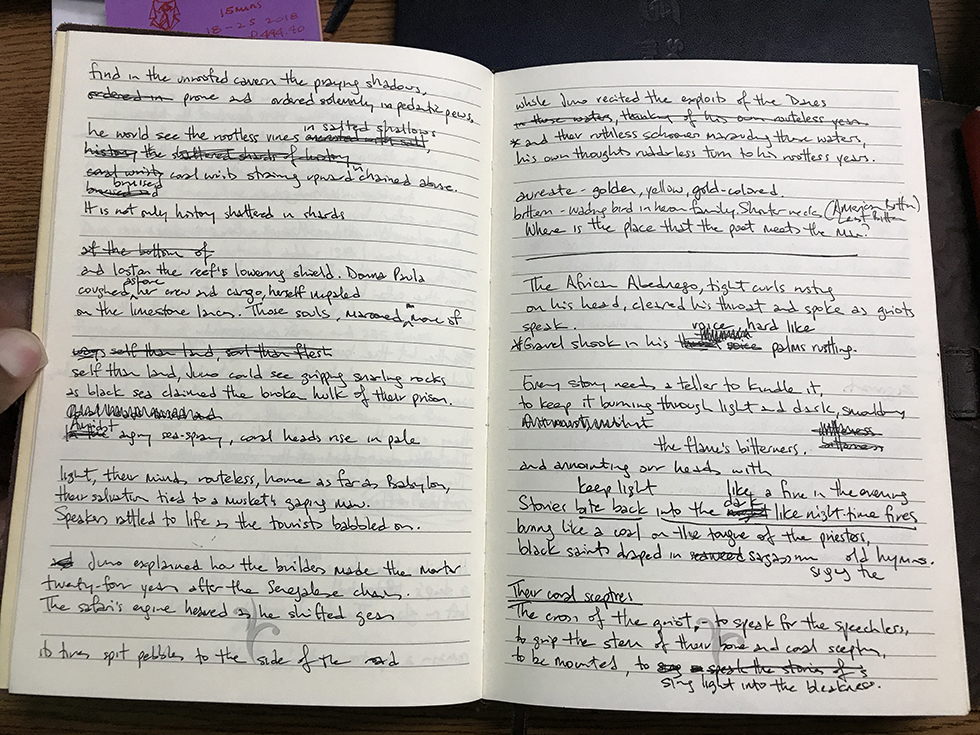

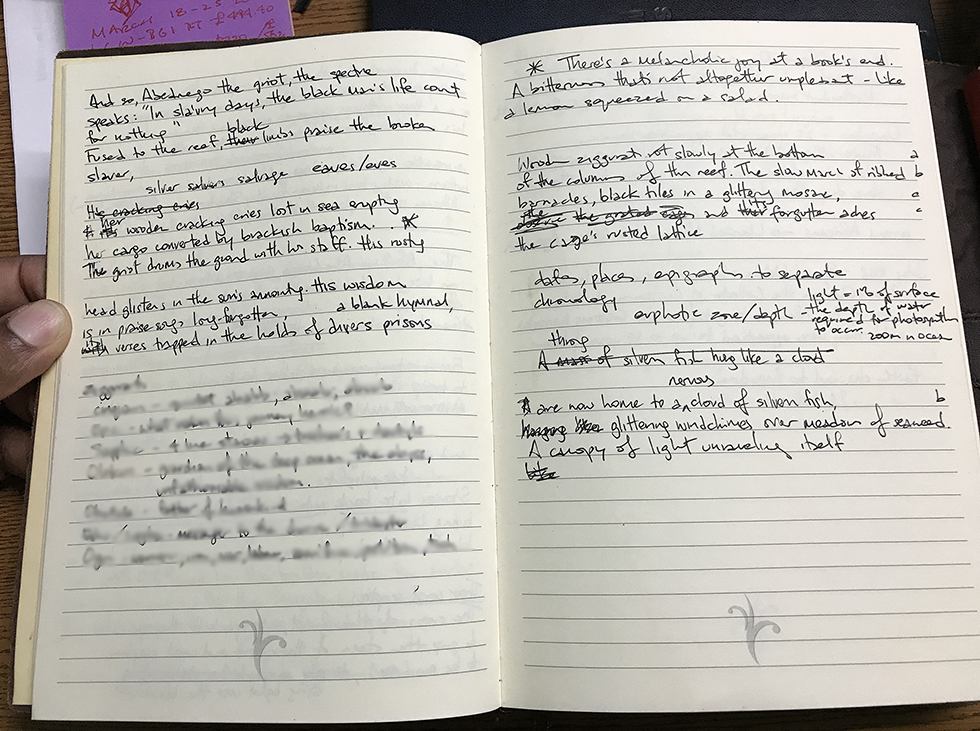

Like most of my work, this poem started as a scribbling in my notebook sometime in 2013 consisting of observations, loose descriptions, and the quote from the mysterious Abednego that I lifted from the epigraph of The Hanging of Arthur Hodge (John Andrews’ self-published book on the infamous slave owner and sociopath who was hanged for murdering the enslaved man Prosper): “In slav’ry days, the black man’s life count for nothing.’ That line ending up being the main provocation for the final draft. I started thinking about who Abednego was, the biblical history of the name, the easy allusion of the prophet unburnt in the furnace, until the troubling thought of who has recorded his reflection. That way of thinking about things gnawed at me, how much Abednego’s story was no longer his, but instead co-opted and exoticised even in this one line. This is when the title and the approach the piece required manifested itself.

At the time of writing, I was experimenting with different forms and ‘Griot’ is one of 7 or 8 written as a relaxed tercet. As such, I transcribed my notes into the word processor and began the working/writing of the poem. With those thoughts of the sovereignty of Abednego’s voice very much at the forefront of my mind, the first lines came easily:

The African Abednego, tight curls rusting

on his head, cleared his throat and spoke as griots speak.

Gravel shook in his voice like palm fronds rustling.

The poem stalled here. I went back to my journal later and edited a few times, and you can see the lines I crossed out as well as how the final draft came to be. I think it is important for the poet to trust that first voice that a poem appears in, insomuch as that first voice often contains a several different possibilities that cannot all be explored. Now, I may try to split that voice and discover more than one poem, but more often than not, it is a process of whittling away and discarding to find the right direction and emotion that I need to capture.

It is tempting to frame writing through the prism of inspiration – of divine or supernatural intervention if you will – and while there is an element of the ensnaring of the subconscious, a lot of what I do is work. I draft poems in notebooks in cafes or at my desk, I draft them on my phone on my daily commute. I transcribe them, and in that process of transcription I begin editing. I shuffle lines and phrases around. I shift in and out of forms, always searching for the right vehicle to deliver the message.

Griot

The African Abednego, tight curls rusting

on his head, cleared his throat and spoke as griots speak.

Gravel shook in his voice like palm fronds rustling.

Every story needs a teller to kindle it,

to keep it burning through light and dark, smouldering

and anointing our heads with the flame’s bitterness.

Stories keep light like a fire in the evening,

burning like coal on the tongue of the priestess,

while black saints draped in sargassum sign the old hymns.

The cross of the griot – to speak for the speechless,

to grip the stem of the bone and coral sceptre,

to be mounted, to sing light into the bleakness.

And so, Abednego the griot, the spectre

speaks: In slav’ry days, the black man’s life count for nothing.

Black limbs fused to the reef praise the breaking slaver,

her wooden cracking cries lost in sea erupting,

her cargo converted by brackish baptism.

The griot drums the ground with his staff. His rusting

head glistens with the sun’s anointing. His wisdom

is in long forgotten praise songs, a blank hymnal,

its verses trapped in the holds of divers prisons.

Richard Georges is a writer and educator in the British Virgin Islands. His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Prelude, Smartish Pace, The Puritan, WILDNESS, The Caribbean Writer, The Rusty Toque, Wasafiri, and elsewhere. He is the author of Make Us All Islands (Shearsman, 2017), which is shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection, and the forthcoming GIANT (Platypus Press, 2018).

Richard Georges is a writer and educator in the British Virgin Islands. His poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Prelude, Smartish Pace, The Puritan, WILDNESS, The Caribbean Writer, The Rusty Toque, Wasafiri, and elsewhere. He is the author of Make Us All Islands (Shearsman, 2017), which is shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection, and the forthcoming GIANT (Platypus Press, 2018).

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.