The Poetry School asked the five poets shortlisted for this year’s Forward Prize for Best First Collection to write about the process behind their award-nominated work. Over the weeks leading up to the award ceremony on 21st September, we’ve published ‘How I Did It’ articles by Maria Apichella, Nick Makoha, Eric Langley, and Richard Georges. In this final instalment, on the day of the Forward Prizes, Ocean Vuong writes about his poem ‘Seventh Circle of Earth’.

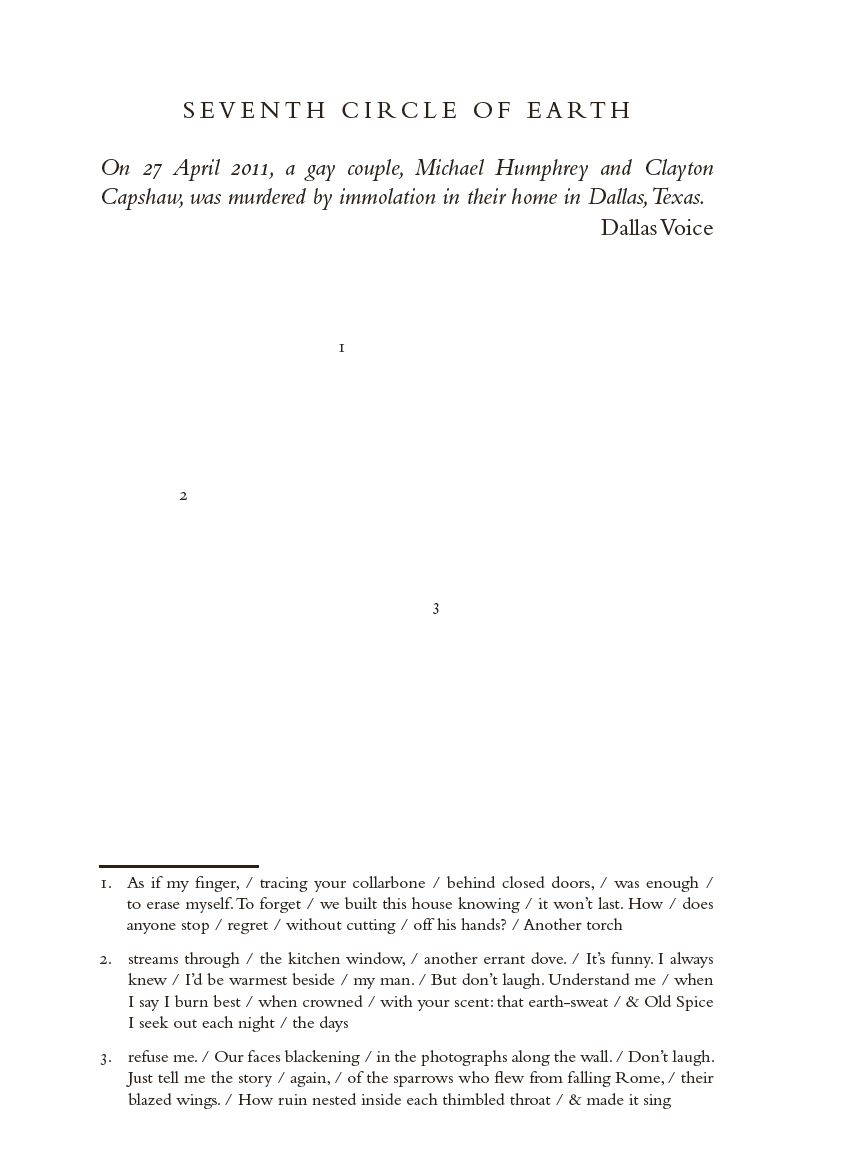

I wrote “Seventh Circle of Earth” shortly after hearing the news of two gay men being murdered by immolation in Dallas, TX. I originally wrote the poem in tercets, echoing Dante’s terza rima format. In the Inferno, the stanzas work as a network of rooms the speaker moves through as he descends through the circles of hell. In “Seventh Circle of Earth”, however, this grouping felt off, even fraudulent, to me. A persona poem at its core, it takes on the voice of one of the men speaking to his partner. And in the midst of that fraught position, a poem in tercets, or, in other words, a “traditional” poem, felt like a diluted, forced recasting of a horrific event. I ultimately abandoned the poem.

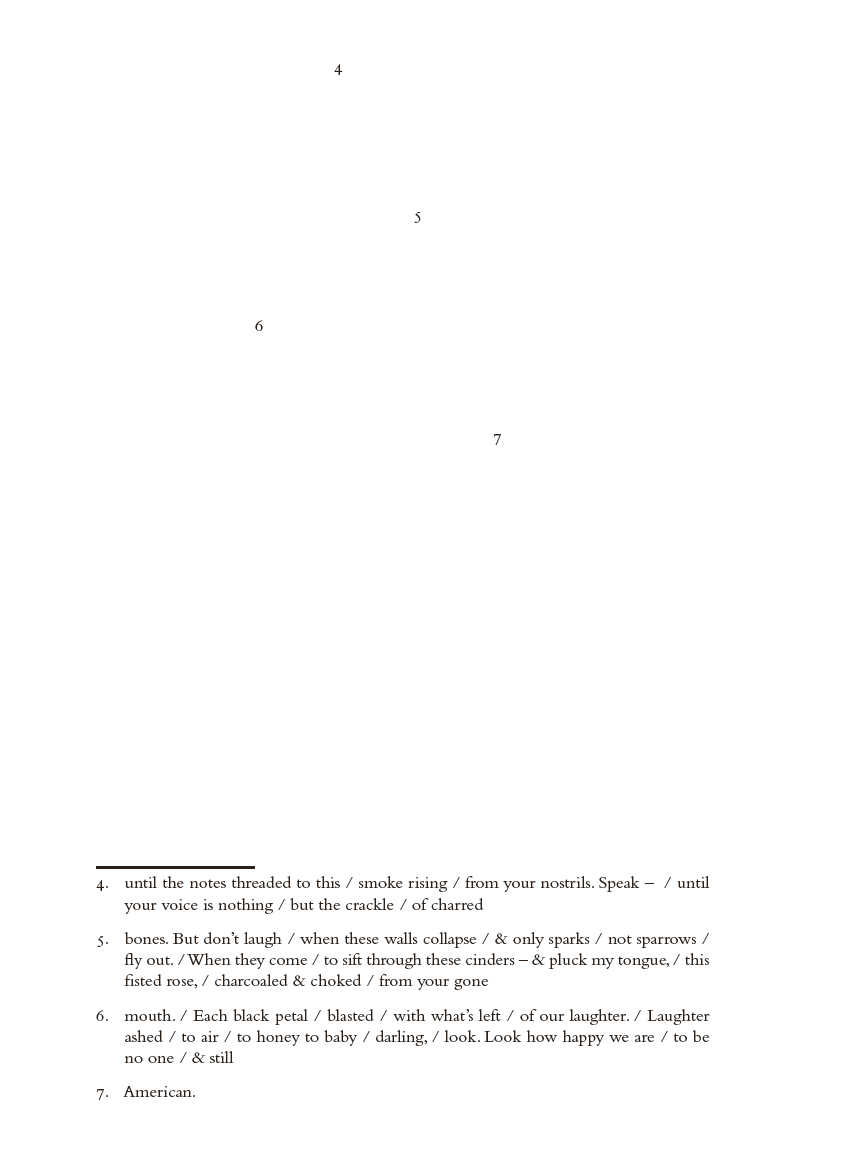

It was not until three years later, while reading a critical work on violence and scholarship, did I see, more clearly, the footnotes on the bottom of the page. I found myself slipping right to the notes as I progressed, reading them first. They possessed, in that reading, an urgency that began to stitch itself into a fabric of broken utterances fused together by parataxis. It was, in a way, found poetry. That gave me the idea to re-work “Seventh Circle of Earth” into a piece written entirely in the footnote. This time, the vast and utter emptiness one confronts on the page felt more faithful to the violent erasure of the two murdered men. It felt right to begin the poem with its own vanishing.

The words appear as a collapsed speech, something that was once “somewhere else,” fallen. But I hope that the form speaks, enacts, also, that for those in the margins who are perennially silenced, the footnote can be a place one gets to tell one’s story. That because the main stage has been obliterated does not mean all hope of speech is lost. And perhaps taking over the primary space is not the only method, and that changing or charging the forgotten space, the after-thought, with new power is also a subversive possibility.

I learned writing this piece that perhaps there is no such thing as complete abandonment of our work, but only a waiting, a collecting, a quiet harnessing of possibilities. That a poem might not fail so clearly as we think it does — but has only yet to find the right bones to stand in, or, in my case, to fall away from.

Poet and essayist Ocean Vuong is the author of Night Sky With Exit Wounds, winner of the Whiting Award, finalist for the Kate Tufts Discovery Award, and a New York Times Top 10 Book of 2016. A Ruth Lilly fellow from the Poetry Foundation, Vuong has received honors from the Lannan Foundation, the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, The Elizabeth George Foundation, The Academy of American Poets, and the Pushcart Prize. His writings have been featured in The Atlantic, The Nation, New Republic, The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Village Voice, and American Poetry Review, which awarded him the Stanley Kunitz Prize for Younger Poets. Born in Saigon, Vietnam, he immigrated to the US at the age of two as a child refugee. He lives in Western Massachusetts and teaches at UMass Amherst’s MFA for Poets & Writers program.

Poet and essayist Ocean Vuong is the author of Night Sky With Exit Wounds, winner of the Whiting Award, finalist for the Kate Tufts Discovery Award, and a New York Times Top 10 Book of 2016. A Ruth Lilly fellow from the Poetry Foundation, Vuong has received honors from the Lannan Foundation, the Civitella Ranieri Foundation, The Elizabeth George Foundation, The Academy of American Poets, and the Pushcart Prize. His writings have been featured in The Atlantic, The Nation, New Republic, The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Village Voice, and American Poetry Review, which awarded him the Stanley Kunitz Prize for Younger Poets. Born in Saigon, Vietnam, he immigrated to the US at the age of two as a child refugee. He lives in Western Massachusetts and teaches at UMass Amherst’s MFA for Poets & Writers program.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.