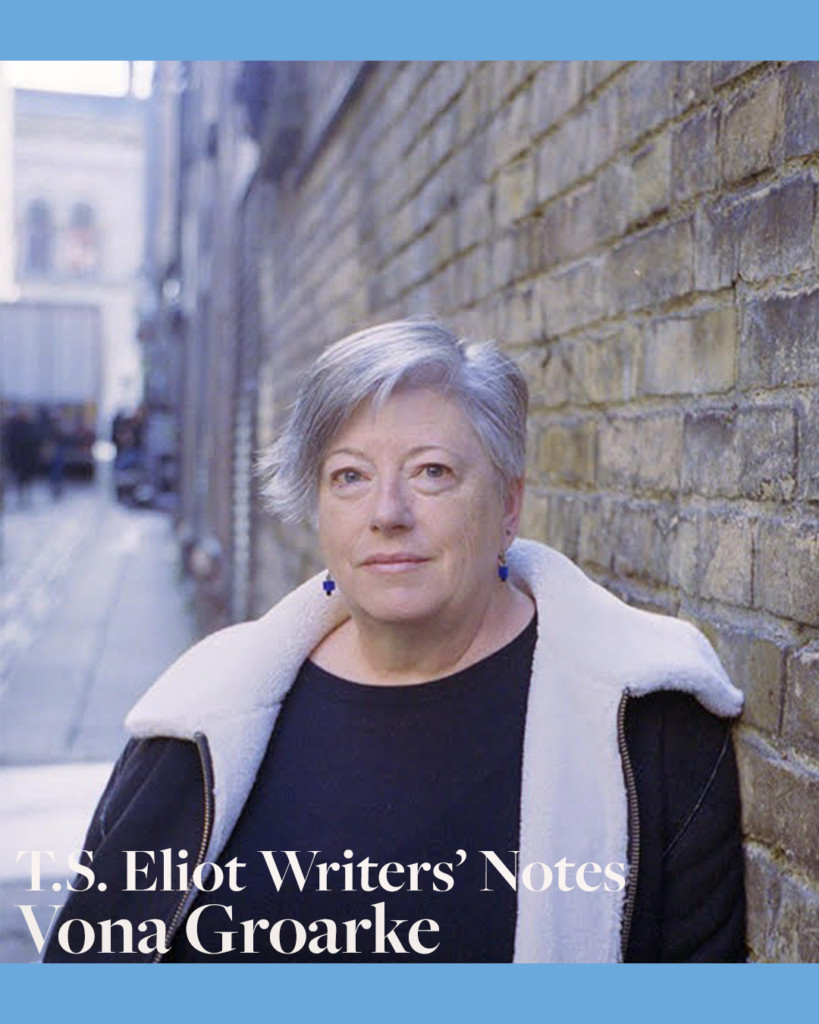

Welcome to our Writers’ Notes for the 2025 T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist. These are educational resources for poets looking to develop their practice and learn from some of contemporary poetry’s most exciting and accomplished voices. Here’s Vona Groarke on her collection Infinity Pool.

Floaters & Flashes

I’m deeply suspicious of the term ‘my practice’ when used by poets: to my ears it smacks of the funding application. I think it’s a charlatan giveaway phrase: it allows people to, as my mother would have said, ‘give themselves airs’, to take themselves more seriously than they probably should for the good of what they write. When a poet talks about ‘their practice’, I can’t help it, I think: Oh, grow up. I don’t have a practice: I’m neither a doctor or a nun. I just write poems whenever and however I can. And when I’m not writing, I think poems. I see them flickering in the corner of my eye, like those floaters and flashes we’re warned about. I might be conversing with someone on the road about nothing or everything, my poetry self nicely muffled under layers of ordinariness, and then it happens: a phrase gets used, or they throw in a good simile, or two cars the exact same make and colour cross on the street and I notice the drivers smile at each other, or the wind blows on an electricity cable like it’s a tin whistle, or a child in a buggy starts crying and its mother straightens and looks for all the world like she’ll cry too, and suddenly, the world shucks off its ‘No way I’m a poem. I hate poetry’ guise, and then I’m off again. Is it what I do, or is it what happens to me? Or some meld of both? I’d say that, in so far as I understand the world at all, I understand it through sounds and images – through poetic language, in other words. I suppose I’d say I practice poetry and I just keep practicing.

If You’re Feeling Gamey…

Every poet has to find their own useful techniques, and the only way to do it is to do it. Poets are full of great advice which is mostly risible. Here’s mine: take two poems, any poems. Replace, in the first instance, the nouns of one with the nouns of the other. Observe the difference. Revert. Repeat with verbs. If you’re feeling gamey, write the first one out, longhand, as prose. Make a cup of tea. Come back to the prose and play for ten minutes with inserting line breaks where you think line breaks should be. Compare with the original. Think about your choices and the poet’s. Apply the same scrutiny and thinking to any poem of your own. Anatomise it, tinker with it, unstitch it, tease. Don’t let it pull the wool over your eyes.

Take It or Leave It.

What does my editorial process look like?

Like nothing I’ll ever talk about in public, thanks very much. Would you ask a new mother about the sex she had that spawned the child? Or ask a bride heading down the aisle if her bowels had moved that morning? I write poems and occasionally publish them: that’s what I send out into the world for the world to take or leave.

Transports of Bliss

For inspiration… Honestly? Any book of poems will do, even a bad or a mediocre one. Of course, the good ones are the most useful of all, but there are so few of them and my idea of a good book might be so different to yours I’m not sure there’s much point in a roll-call. But even a not-great book (best encountered in a library or second-hand shop: save your heard-earned for the good stuff) can set something resistant in you going. Annoyance is as good a place to start from as transports of bliss. (You won’t want the poem to end in annoyance, but it might work as a launching position.) You have to start somewhere and reading any poem seems to me to help bridge the gap between the language of the day-to-day (useful for buying onions and filling up job application forms), and language that can’t be replaced by AI, that wants to be harder-working, more careful, spry, eye-catching (and mind-catching too). I always recommend anthologies or poem-a-day websites to students as a decent-enough shallow end, the point being to find the poems you really like and then to go a little deeper with those poets. Most students never do, of course, but that’s a very handy indicator of the ones who actually have an outside chance of getting to grips with this sneaky, slippy, knotty, land-mined, highly resistant, art.

That Sly Niggle

How to know when a poem is ready? After thirty (plus) years of writing poems, I find the poem sort of whispers to me, ‘You can go now. We’re done here.’ Perhaps the only piece of writing advice I can offer that I believe might actually be useful (as opposed to all the writing advice I give to fill the paid hour or to sound like I know what I’m talking about), is: Never, ever ignore that niggle of knowing something’s a bit off about a poem. Don’t send it anywhere until you’ve made that niggle go away. It’s so easy to do. You think the poem’s, for the most part, doing what it and you want it to do. No one (sane) will notice that little image that doesn’t quite get over the bar, or the phrase that overshoots, or the clunky line break (that is, after all, entirely justified by the complex metrics of the schematic), right? Not with the world the way it is, with the wars and climate change and the price of housing, right? And maybe they won’t, but you will: you’ll never be on easy terms with the poem as long as it’s there.

Allow It

It’s a sly one, that niggle; so sly that, sometimes, you can’t even quite find it or give it a shape, co-ordinates or raison d’être. Other times, when you think you’ve got the upper hand and made it slouch off, tail between the legs, there it is again, larger than life and laughing at you now, nasty as this metaphor, twitching your eye and pulling your hair, spitting at your back. The only way to put manners on it is to get rid. You’ll know when you’ve finally managed it: you always know. And not just because it’ll probably say, ‘Fair play’ (mine always does, but that probably says more about me than my poems), as you’ll be too pleased with the way the poem’s come right, eventually, to even hear the words. But here’s the thing about that niggle: it’s a shapeshifter. You’ve never quite seen the last of it. It’ll be back, never fear, the next time you sit down, all innocence, to write. (Mine’s neon yellow, by the way. And it always carries an outsize sewing needle, one of those with a dirty great curve in the middle. And it wears fingerless gloves.) Which is fine, the poem will be glad enough to see it: it’s the poem’s first line of defence against the poet’s ego, with all its hectoring intent. Allow it. Accommodate it. You absolutely must.

For the Greater Good

I find by far the most satisfying response to rejection is to say, ‘Fine then. **** You’. Especially to those ones that mean well but are deeply patronising, that say: ‘We thought it was a pile of goat-dung but you might just find another editor who really likes goat-dung. Because, hey! we’re all different. Good Luck!’

But while the asterisked one is a fine first response, it cannot be the last. I’ve been an editor myself; it’s never fun to disappoint people you know may be deeply invested (sometimes, over-invested) in the work they’ve offered you but, inevitably, there’s so little available publishing room that you have to be brutally selective. Rejection is a necessary part of the process: a great deal more not-great poems get written than great poems and, for the sake of this art we say we value, we mustn’t offload our collective critical faculties. Quality must be assessed: ideally, only very good poems would ever cross a reader’s path and it’s an editor’s job to apply judgment as to what constitutes just that. What would have to be far more dispiriting than repeated rejection, surely, would be repeated acceptance, so you couldn’t tell Good from Not Very? When we lose sight of how to discern the great poem from the almost-great or, indeed, from the abundant very bad, we fail the art. When editors publish poor or so-so poems by even established poets, they fail the art. When reputable publishing houses do god-awful books they’ve grafted onto their lists from Instagram or TikTok, they fail the art. When funders, programmers or readers prize ‘relevance’ or ‘engagement’ over craft, we fail the art. I’ve always believed that the enemy of art is cynicism, and rejection offers, at least, an honest response.

Cherish Rejection! Get to Work…

So, for the sake of the greater good, cherish rejection! If you’re serious, then sit down straight away after rejection and try to write better poems. And if rejection really, really upsets you (and bleeds into your whole sense of self), then you probably should stop sending out. And if not sending out means you stop writing poems, then maybe that’s fine too. Do something else. It shouldn’t be easy, no art is, and this one definitely isn’t. Big deal. How do I move past it? I move past it. I get to work.

The Poetry School and T.S. Eliot Foundation have long collaborated on celebrating the T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist, highlighting this major fixture in the poetry calendar as a fantastic way into the art form and an opportunity to learn from poets at the top of their craft. This year we have a series of Writers’ Notes from the shortlisted poets.

Vona Groarke has published fifteen books, including nine collections of poetry with the Gallery Press, most recently Infinity Pool, shortlisted for the 2025 T.S. Eliot Prize. Hereafter: The Telling Life of Ellen O’Hara – a poetic account of Irish women domestic servants in 1890s New York, which arose out of her time as a Cullman Fellow at the New York Public Library 2018-19, won the 2024 Michel Déon Award. Her Selected Poems was awarded the 2017 Piggott Prize for Best Irish Poetry Collection. Recent poems have appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry (Chicago), The Poetry Review, New York Review of Books, and the TLS. 2017 recipient of the Irish Literary Hall of Fame Award, she is a member of Aosdána, (Irish Academy of the Arts), and of the Royal Society of Literature. Former editor of Poetry Ireland Review and poetry critic for the Irish Times, she is Writer in Residence at St John’s College, Cambridge (2022-26), and has recently been inaugurated by the Irish President as Ireland Professor of Poetry (2025-28). www.vonagroarke.com

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.