Selam hullu…..Hello everyone!

I’ve already blogged about my boyhood in Addis Ababa as an intro for my autumn 2021 course on Childhood: A Source of Praise.

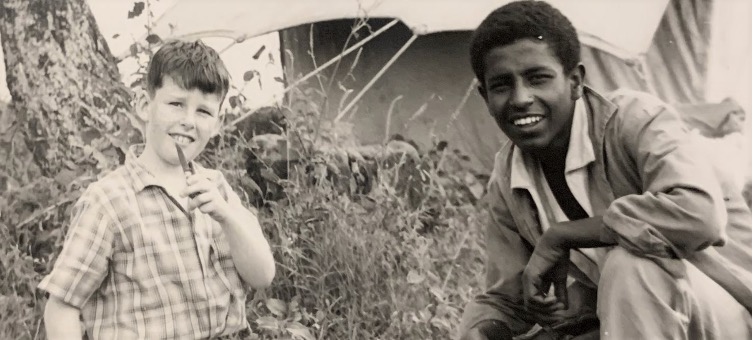

So I don’t want to repeat too much of what I said then, but it feels like I’m travelling the same path again! It’s a really great feeling, because I remember how chuffed I was when I started getting to grips with Amharic as an adult, knowing that I was discovering poems and poets who my friend Abebe would have learned at school in the 1960’s. Abebe loved music and song, anything to do with live performance, so maybe he even went to poetry readings at the University or in hotels and clubs, just like I have been doing in the past few years. If Tilahun was the coolest Ethio Jazz singer of the day, closely followed by Mahmoud Ahmed and Hirut Bekele, then poets like Gemoraw and Mengistu Lemma were also household names in the last decades of Haile Selassie’s empire, often leading the way in edgy or even outright revolutionary social commentary.

When I look at an old picture of Hirut Bekele, I just want to start clicking my fingers like her and like Abebe! I can feel the beat in my head, because Ethiopian song lyrics largely follow the same 6/12 syllable lines of folk poetry, like Tilahun’s የሃገሬ ሸታ/Ye hagaré sheta, meaning The Smell of my Country or Hirut Bekele’s አውነትኛ ፍቅር, Awnetegna Fiqer (True Love).

There is an old and enduring tradition of minstrels in Ethiopia, called Azmaris, famous for making up verses which they sing in front of you in a tella or t’ej bet ie a beer or mead house, or what we would call simply a pub! He or she praises the drinking client, often with a witty barb as well, about your wealth or weight or baldness or…and however rude the singer is about you, you laugh and pay up. To help the azmari make up these improvised verses and sing them on the spot with his single-string masenqo, they tend to follow the pattern of a rhyming couplet of alexandrines, i.e. 12 syllable lines with a pause after 6 syllables. For me this is the same drumbeat that sounds through most Amharic folk poetry and spills over into literary traditions too; it is the basic building block that poets still either incorporate or rebel against, cut up, endlessly play around with because you know, as an Amharic poet, that your readers will have the rhyming couplet in their head since childhood.

The other trait is what they call Wax & Gold (Semenna Worq), which means the use of homophones to add different layers, to talk about something sexy or political under a quiet surface. In a traditional, mostly censored society, this makes poetry very exciting. Almost impossible to translate too!

When I went back to Ethiopia in 2007, almost exactly 40 years since I had left as a child, it was a bit of a shock to realise that I understood hardly a word that people were saying! Naively I’d expected the language would come back to me, like riding a bike. Maybe I’d never spoken that much Amharic as a boy anyway. But hearing people speak it around me took me back to the 1960s and made me feel excited, like a boy again. I took lessons at SOAS in London, and though I’m still not that good at it (I think you have to live in a country to really get under the skin of its language), I can read and I love working out what it means. Poems are hard, but there are always friends, mostly one really great friend, Alemu Tebeje, who will help me out. Translation feels to me like riding that bike, there’s many times I fall off but I’m always glad to be on it…if that’s not stretching the metaphor a little far! Poetry is completely mainstream and important to everyday life in Ethiopia. Two of the female poets in our anthology, Songs We Learn from Trees, Mihret Kebede and Misrak Terefe, started a poetry and music event series called Tobiya Poetry and Jazz which meets monthly at the Ras Hotel in Addis. Hundreds of people turn out every time to listen to poets who are household names just like the 20th century greats used to be. The audience is vocal and appreciative, often emotional in response to the poems

In a way, I am going for the same sort of emotional connection but with my inner self when I study Amharic poetry because it feels like the soundtrack of my boyhood. It is fascinating in itself in so many ways, but the process of looking for your own impulses in a different poetry is to me as important as the particular poetry itself

I hope we can unpack some of the characteristics of this poetic process, by looking closely and having a go at translating some Amharic poetry together.

To explore this topic further, join Chris Beckett’s upcoming Summer Term course, Transreading Ethiopia, which will run 19 May – 28 July.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.