As we’re sure that most of you reading this are already aware, Roddy Lumsden very sadly passed away on January 10th 2020, after a long period of illness. In his passing, the poetry world has lost a true titan. Roddy was an acclaimed and innovative poet, an inspirational educator, a generous mentor, and a fastidious editor; he was a formidable quizmaster, a mischievous raconteur, and an endless mine of trivia, esoteric, and obscure knowledge. He was, throughout his whole life, a tireless reader, promoter, and advocate for poetry and poets of all ages, styles, and stages in their careers. His work in curating the landscape of contemporary poetry – bringing countless poets into the writers they are today through his workshop groups, regular live events, and editorial input – cannot be overstated.

Here at the Poetry School, Roddy was a truly foundational figure. He joined the School in its very early years and fast-became a key figure in our faculty, working with a great many of our students and tutors over the years, alongside being instrumental to the development of our MA Programme. As one of the Poetry School’s founders, Mimi Khalvati, put it: “he was absolutely instrumental in making the School what it is today”.

To celebrate Roddy’s lifelong work in poetry, we have collected a series of testimonies, tributes, and memories from his previous students, colleagues, and friends, which we have compiled below. Do take the time to read through these touching and heartfelt reminiscences; you will see a huge array of writers here, ranging from the much-celebrated to those very early in their careers. We think these memories show a true picture of Roddy, his life’s work, and the inestimable influence he had on contemporary poetry.

Although the poetry world has suffered a great tragedy in our loss of Roddy, we take comfort in the fact that his legacy lives on in the sheer range of voices writing today and the countless volumes of poetry published with his name in their acknowledgements.

– The Poetry School team

Mimi Khalvati

Roddy joined the School as a tutor in its early years when he himself was on the cusp of becoming the celebrated poet he became. We were so glad to have him on board and of course he proved to be such a stalwart and essential part of the School, especially in introducing experimental and American poets into the curriculum. At the time, Roddy lived in Stoke Newington where I still live, and it was lovely to bump into him sometimes and chat on street corners, as well as meeting up after our classes in Lambeth and sharing notes. Through the years, many of his students have told me how much they valued his teaching and encouragement and how lucky they were to have been in his circle. He will be hugely missed, by his students, friends and also his readers and the poetry world. I feel profoundly grateful to Roddy for everything he gave us. The Poetry School became a big part of his life and he was absolutely instrumental in making the School what it is today. We will always think of him with gratitude and warm affection.

Tamar Yoseloff

Apart from being a great poet and colleague, Roddy was an inspirational tutor, who was generous in his support and assistance to those who studied with him at the Poetry School. He influenced an entire generation of poets, many of whom have since been anthologised, published and awarded prizes. Some have come back to teach at the School, bestowing Roddy’s gifts to yet another generation. For so many poets to whom he was both mentor and friend, he will be very much missed.

Julia Bird

Roddy and I once left The Poetry School after work to head to The Pineapple. ‘Right’ he said ‘Over the course of this pint, the situation will change from you being my boss to me being your boss’.

The poetry world is a pile of overlapping portfolio careers. Mine as a poet and education programmer [programming courses for the Poetry School from 2005–17] overlapped with his as an editor and teacher. The afternoon we went to The Pineapple, he’d been teaching the Poetry School course that I’d programmed, but was also working on the manuscript for one of my Salt collections, and had notes. As anyone edited by him will recognise, his amends were more often than not related to my inaccurately deployed semi-colons and incorrect spelling of the word ‘minuscule’. The seesaw of who was giving what to whom never settled in one place, and our conversations were kept lively because of it.

Roddy was a beloved tutor – we saw his classes sell out again and again. Much has already been said and written about his mentoring of younger, emerging poets – but he knew as well as any that new talent doesn’t only inhere in the 20-something writer. His classes filled up with senior, experienced writers, working through a photocopied flurry of exemplary poems from distant and challenging sources. His afternoon students loved to bake for him and each other. There was often leftover cake. Poetry School staff appreciated all of it.

Roddy and I moved to London at the same time – him from Scotland, me from the West Country. As I found my community gathering at new landmarks – readings and events at The Poetry Café, The Poetry School, The Betsey Trotwood – Roddy was always there in the middle of it. How sad that he has gone.

Amy Key

The night Roddy died I was a few streets away at my flat, spending an evening with two close friends. No idea what was happening so close by. We were watching videos of Canadian figure skaters Virtue and Moir. One in particular, their final (gold medal-winning) Olympic performance, beguiled us; we were flooded with emotion. It led to a conversation – a game almost – about what music we would each skate to for our ‘short’ and ‘long’ programmes, were we figure skaters. My friend Amy knew immediately: she would skate to ‘Video Games’ by Lana Del Rey for her short programme, and then ‘Permafrost’ by Magazine for her long programme. This was the kind of conversation Roddy adored. The type that entrapped us after closing time in the pub, or at my flat lounging on sofas. He would have immediately known his song choices – with no prevarication – and would tell a compelling story as to why. He would organise ‘records night’ where he’d invite people over and ask them to select songs in various categories – a song from the year you were born, song to be played at your funeral.

When I woke up the next day, still unaware of Roddy’s death, I re-watched Virtue and Moir in bed. It came to me that I would skate my long programme to ‘River’ by Joni Mitchell – give myself a real river to skate away on. I played the song, visualising a routine. As the song ended, I learned of Roddy’s death. I wish I had a river. I loved him.

Oliver Dawson

I was very saddened to learn of the death of Roddy Lumsden. The period whilst I was Director of the Poetry School, 2009-2015, coincided with a time when Roddy was very active in his teaching and mentoring. Although it has been said that Roddy never held down a proper job, the Poetry School was, I think, the closest thing to a job and a workplace that he’d had. He would be teaching at least one weekly course for us – often two – and then there was his private group which also took place at our classrooms on Lambeth Walk, so myself and the staff would usually see him several times a week. Roddy had an enriching impact on the Poetry School. His involvement undoubtedly raised our profile among emerging poets and drew in a different crowd of aspiring writer. Roddy had a pluralist disposition towards the poetry of others and towards poetic style and experimentation. This not only made Roddy a great teacher, editor, and mentor, it also made him a natural ally for the qualities and values I wanted the Poetry School to embody. In my mind, Roddy will always stand for the idea of poetry as a vocation or a way of life. He helped to create a wonderful community of practice around the Poetry School and at large in London. Though our relationship was not without occasional strains and difficulties, I am grateful to have known him and worked alongside him. I thought about Roddy often these last few years and, like many others, I will miss him dearly.

Jimmy & Carol Lumsden

Roddy’s funeral is over – a remarkable day in so very many ways and one which his mother, Betty, described as truly awesome. We have said farewell, but know now his legacy will live on. His family have been left astounded and deeply moved at the tributes paid to Roddy – tributes of such warmth, honesty and generosity of spirit. In these you have introduced us to a Roddy we (sadly) never fully knew, Roddy the poet, teacher, mentor and friend.

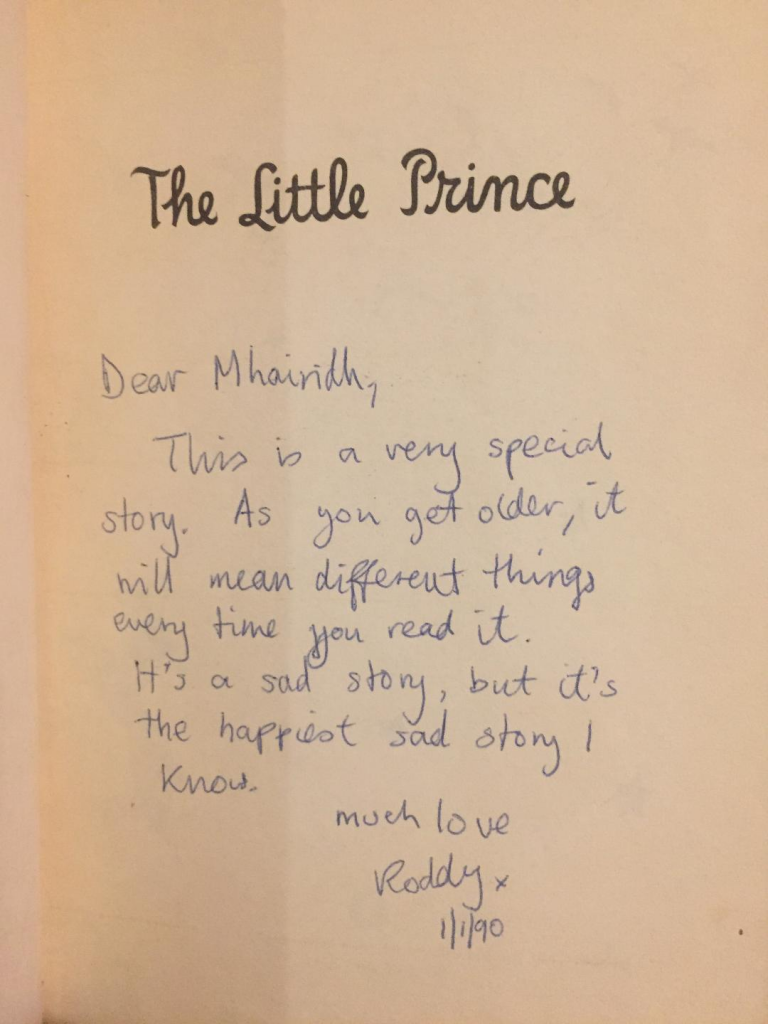

We should have seen this side of our brilliant, complex boy much sooner of course. The signs were clearly there when he took his nieces to the Pear Tree pub in Edinburgh whilst babysitting them aged 9 and 7 so they could improve their general knowledge at the quiz machines. Or the thoughtfulness and gentleness of his inscription in his gift for his niece, then aged 8:

Thank you all for loving Roddy, for caring for him and for being kind.

Thank you for everything his poetry family undoubtedly gave back to him, as he gave to you. And thank you for celebrating him and giving us, his family, the joy of seeing and understanding Roddy the poet and teacher.

At peace. ❤️

Inua Ellams

Roddy and I.

I’d been running around manically writing everything in every way, when Roddy invited me to join his class at The Poetry School in 2006. When I got the invitation, I thought there had been a mistake, that he meant to invite someone else. When I realised there was no error, I asked if I could join his beginners class. Roddy categorically refused, insisting I join his advanced class, adding that should I refuse, he wouldn’t allow me in any class, whatsoever.

At the time, I was still an overstayer, an illegal immigrant. My status made attending university a financial impossibility. I felt uneducated and lacked confidence in writing, in speaking, in public readings, and I felt unwelcome and unsafe in almost every space I entered. Yet, Roddy Lumsden, one of the most respected poets in the country, had personally invited me to his advanced class. It meant he had seen something in me, and had confidence in my ability. It was momentous, it felt surreal and Roddy seemed luminous, luminary.

In my first lesson, Roddy quoted a line of my own poem to me, in front of the whole class. He called himself a ‘benevolent eloquent elephant’, praising the poem and the verse in which I’d employed the line. Though I had come from a performance poetry background, Roddy deliberately praised the writing and wanted to do away with any suggestion of any indelible divide. He saw me, and wanted me to be seen by my peers.

I attend the class for over five incredible years in which I discovered that Roddy was in fact luminous and luminary, sometimes in subtle, sometimes blunt, but always profound ways. He coached, engineered and challenged us all. He spurred myself, Ahren Warner, Wayne Holloway-Smith and Adam O’Riordan to start New Blood, a poetry event series, to celebrate and reflect our diverse literary interests. He set up countless events, one-day-festivals to share us and our work with the wider world. He championed and platformed us, time and time again.

Roddy encouraged me to enter the Eric Gregory prize and was so staggered to discover that its archaic rules made me ineligible, that he began lobbying its organizers to change them. In so doing, Roddy was actively trying to decolonize a British Institution, which is it say, as much as Roddy was within and actively contributing to his immediate world, he was also ahead of his time.

In the last few classes I attended in 2011, I shared a poem which again Roddy enjoyed and dissected in the class. He underlined a description of a boy I had gone to school with, ‘The Half-God of Rainfall’, and asked where the image had come from, praising its ingenuity. That conversation led to the epic poem of the same title that became a play, published and staged last year. It took almost nine years to write, throughout which Roddy’s voice and progressive spirit was in my head and in my heart.

When the Eric Gregory Prize rules were eventually changed, my age made me ineligible. A few years later, I was asked to become one of its judges. I accepted to honour Roddy, that I might be able to change a younger poet’s world, as he had so changed, deepened and enriched mine.

We have lost a titan, a teacher and a good man, but his influence will live for generations to come.

Jacqueline Saphra

Roddy was an inspired and intuitive creator of community. At some point in the early 2000s, he gathered the unlikely trio of myself, Gale Burns and Amy Key together and somehow persuaded us that it would be a good idea for us to start a regular reading series at The Poetry Cafe. We spent several feverish evenings with him, thrashing out the inner workings of the proposed event and, like a teenage band, we squandered an inordinate amount of time searching for name for it. Eventually, The Shuffle (which is still running), a monthly poetry reading series, was born. We, a mismatched but determined triumvirate, ran this thing together for some years; many of our performers were Roddy’s students and have gone on to publish first, second and third collections. We ourselves made three pamphlets of the best of The Shuffle and some of this country’s finest poets’ work can be found between their covers. Those were heady days, as they say: some of our readings were so full, we had people sitting on each other’s laps, or perched on the stairs up the café. Roddy, ever-loyal, was almost always present and sometimes read for us too. I cut my teeth as an organiser on The Shuffle; I would never have thought of myself as that kind of creator, but Roddy must have seen I had it in me. He had an eye for that sort of thing.

Annie Freud

Roddy was a dear friend of mine for many years. He showed my poems to his students. He knew some of them by heart and would recite them under his breath when he came to hear me read.

In July 2011 we led a residential weekend workshop in small cliff-top pavillon overlooking the sea at Eype, a mile along the coast from Bridport.

A few days before the workshop my father died. The rent on the house has been paid, the booking fees had been received, the food had been bought, everything was ready. To cancel would have too painful.

It was a golden, happy time. The sun shone, mostly. We worked, slept, talked, laughed, ate, drank, grilled fish on the barbecue, ran luke-warm baths, and watched the sea and sky and when it was over, we parted.

Afterwards I fell apart.

It is a memory I will always treasure among many others.

You are at rest, dear Roddy.

Tim Dooley

Roddy Lumsden had a huge influence on the contemporary poetry scene. As a tutor, editor and event-organiser he encouraged and enabled several generations of poets promoting the fusion of lyric and experiment, of precision and play that characterise the plural and diverse poetry of the present. As a poet he was a true original, who has left a body of work which is moving, entertaining, and provocative.

Luke Kennard

One of the last times I saw Roddy was in 2012 when he was editing for Salt and we worked on my 4th collection together. I gave him around 200 pages which he trimmed down to 50 and then sent me away to write some new poems, some different poems; have you ever considered trying to write a love poem? Like even just trying to? He always asked the right questions about your work, the tricky questions, and he always gave you permission to take your work seriously, as seriously as he took it, which is something rare and generous. I know that he did that for so many people. I know that he’d talk to you – after a reading, a ceremony, wherever – with an urgent kind of confidentiality, as though you were backstage at something important, and with all the attendant glamour and scandal. And it didn’t matter if you were a published writer or if you’d just read your first 3 minute open mic slot and you were still shaking: to meet him was to immediately be taken into his confidence. He talked to you as though you were already part of some kind of scene and made you feel that you were. I first met him in 2005, having studied several of his poems at university, and there was already this sense of excited anticipation – which I felt standing outside the poetry café with a badly rolled cigarette – that he was starting something, that the poets he was working with and the ones he was going to work with were going to… I don’t know – were going to write some great poems, is what it comes down to in the end… almost a sense of impatience.

He came to Birmingham for a final editorial meeting in 2012 and I’d tried to write some love poems, and they’re ones I still do at readings sometimes. He’d damaged a fingernail on his right hand and it had got worse so his hand was bandaged. We talked about embarrassingly minor injuries which are actually really annoying and impact on your basic function until we had a definitive list of Minor Injuries which are Nonetheless Somehow Disproportionately Encumbering. Because he had the kind of mind which could draw an encyclopaedic theme out of anything. (I remember him referring to a conversation he had with friends about consuming small bits of yourself, fragments of fingernail, lip skin, etc. and I still think about that every time I consume a small bit of myself). I walked him back to his hotel and we had to shake left hands, after which I turned around and walked, very fast, directly into a temporary food shack which had been put up outside The Yardbird, hitting my forehead hard enough that when I caught my reflection in Paradise Forum there was blood running down my face.

But yeah, mostly I remember him as the kind of poet and editor who allowed you to become yourself; who got you reading stuff that changed you; and who pushed you to write poems that could potentially be something like that for other writers one day. In the big endless continuum. And I’m grateful, and so sorry for those who knew and loved him.

Mark Waldron

I went to Roddy’s workshop for about 10 years and would still be doing it now if he hadn’t become ill. He was one of the most uniquely himself people I have ever met, and I miss him very much.

Daljit Nagra

I was so grateful for Roddy’s support and endorsement when I first started out as a poet. He went out of his way to offer insights about my poems and I enjoyed our conversations about the craft of poetry and the exciting new poetry being written at the start of the millennia. I will miss him.

Chris McCabe

When I was in my late teens and early 20s, writing poetry and starting to read as widely as Liverpool Libraries stock allowed, Roddy was one of the few contemporary poets whose work really excited me. Roddy’s poems are always front-ended with invention, I found all his books, read them multiple times, wanted to own them. A few years later I found myself working at the National Poetry Library and one day Roddy Lumsden came to the front desk. Here was the man himself, easily recognisable from his author picture, yes that one, the one everyone knows. He was very humble about being spotted, ‘doesn’t happen often’ he said. I helped him find a particular Scots book, maybe W.D. Cocker’s Poems Scots and English from 1932 or was it Hurlygush by Maurice Lindsay? Now I look more closely at the library’s catalogue I think it must have been William Soutar’s Riddles in Scots (1937), if there was a book of Scots riddles in existence Roddy would find it. This was the start of dozens of conversations about poetry I had with Roddy, many of them in pubs, many of them in the National Poetry Library. When we were teaching classes at the same time we would sometimes walk together from the South Bank to the Poetry School in Lambeth. We always talked about poetry, sharing what we were reading, making connections, looking for the next bright thing.

Rebecca Perry

I once wrote a poem that appeared to mourn the death of a pet. I took the poem to Wednesday group for feedback and, after the usual 10 or so minutes of comments from the group, just as we were moving on to the next poem, Roddy asked if the pet was a dog because this was the sense he had from the poem. I told him that the pet had never actually existed, but was a vehicle for talking about the experience of grief. He was disappointed. It was clear that the poem, and I, had let him down. He talked about how important it was for him that poems were true, though I’m sure he didn’t necessarily mean that they told the truth. It’s something I think about a lot, and not a lesson so much as a philosophy to wrangle with, and pick up and put down, and sometimes accept and sometimes reject, which I suppose is the mark of a great tutor. To me, Roddy was a person who was unfailingly direct, and a poet who put his whole self into his poems. He had time for absurdity and obliqueness, of course, but never screens or half-truths or writing that wasn’t trying to do something ultimately honest or full of feeling or romantic or ridiculous.

With his unique combination of enthusiasm and absolute seriousness, he brought together great gatherings of people to write, read and share ideas. Few people have done so much for poetry, and for poets. I am one of so many who spent countless Wednesday evenings sitting around a table in the Poetry School, then around a table in the Pineapple, gossiping and talking about poetry and attempting to answer his quiz questions. Many of the readings I did early in my career were because of him, my first collection owes a huge amount to him, and most importantly some of my dearest friends came to me via mutual friendship, and so his impact on my life will go on. I know this will be the case for many people.

Dai George

I first got to know Roddy, strangely enough, on a music message board called Black Cat Bone. A famously argumentative but intelligent presence on BCB, Roddy took me under his wing and gave me impromptu feedback and advice via private messages – a process too casual at this stage to be called mentorship, but heading in that direction. He was delighted when I got in to Columbia’s MFA programme, seeing it as my ticket to the wild American frontiers where he felt most at home himself (poetically speaking) in later years. When I came back to Britain and moved to London, he welcomed me into his Wednesday workshop at the Poetry School, no questions asked – though I do remember a dissolute summer Saturday before then, spent knocking about the Blackheath pubs on the pretext of ‘catching Roddy up’ on my American period. He spotted me most of the rounds, and in every new beer garden he produced my dog-eared manuscript and surveyed it with a weary eye, landing on a weak or pretentious passage, jabbing his finger and asking, ‘So what are you trying to do here?’ I was an MFA graduate now, having survived ten rounds with Lucie Brock-Broido and Timothy Donnelly, so I could take it.

I didn’t know what to expect of the Wednesday group. I got muddled with times and turned up late to the first class, but Roddy welcomed me into his Camelot with a wink and some warm words. I can’t remember who’d have been there that night, but safe to say the room was filled with great poets who would soon be cresting the wave, and it was Roddy who was doing most of the work to make it happen for them (for us). I won’t namedrop but that gathering of minds was so important to me – for the friendship I found there as much as for the practicalities of workshopping poems, arguing the toss over taste and principles, and gossiping about po-biz. Roddy’s teaching style was low-key, personable, sometimes ramshackle but absolutely essential to the culture of that group. He’d hover at the head of the table asking open questions about the poems he’d brought in or setting us quirky writing prompts. (His prompts were the best, and could only have come from from that great store room of wordplay and trivia that he carted around in his head.) When chairing the discussion about poems that we’d brought in, Roddy let the conversation flow but usually drew things to a trenchant point – he conveyed a lot with a spare ‘Yeah’, or ‘I’m not sure’, or ‘Why don’t you try…’ Rarely did he get visibly enthused, so whenever he did you knew you’d earned it. I always loved and valued those two hours spent in Roddy’s class, but I think it’s only lately – now that I’ve started running my own workshops – that I’ve realised the great craft and judgement that went into those sessions. That uncanny knowledge of when to let the room speak, when to let a poem speak, and when to show them what only you can see.

Rachel Piercey

I was so pleased to be in one of Roddy’s Poetry School classes – he made you push your poems further, to make them shine with a stranger, more beautiful light. It felt like being at the heart of something to attend his buzzing events and I wrote some of my favourite poems in response to his prompts. Roddy’s knowledge, fervour, and complete dedication to poetry were an inspiration – he will be missed and honoured by countless poets.

Kayo Chingonyi

My earliest memory of Roddy is from before we knew each other. I went along to a poetry all dayer at the Vibe Bar. This was maybe 2006/7 though I can’t say for sure. Roddy was reading and, throughout, a couple, who’d wandered in on a whim, were talking. Finally Roddy lost his patience and, in more colourful terms, asked them to leave. That moment comes to mind when I think of Roddy because he took the appreciation of poetry very seriously, it was never far from our conversations and it is this seriousness, I think, which meant Roddy’s work kept changing and responding to new influences. Of all the things he taught me, this idea of taking it seriously, even in the midst of ludic excess, has really stuck with me.

Kathryn Maris

In 2006, Roddy and I inherited workshops at Morley College from Greta Stoddart and Maurice Riordan. Roddy, whom I’d never met, stepped into the shoes of our popular predecessors as though he’d been wearing them all his life. His classes were filled to capacity, blazing with the energy of a bonfire, while I was rubbing two sticks together.

Roddy wasn’t always the guru figure he became, but 2006 may have been the turning point. He curated a reading series, commissioning students (and friends and colleagues) to write and perform poems on predetermined subjects, thereby offering his protégés opportunities usually enjoyed by ‘professional’ poets. The thriving D.I.Y scene of the 2010s may owe a debt to Roddy’s innovative projects and publishing activities.

Over time, Roddy led more workshops, including private ones, increasingly focused on younger poets. Because Roddy could access opportunities that I could not (e.g. the Tall Lighthouse pamphlet series, Best British Poetry, and the Salt list), I sent promising young students to him.

I started to notice an odd specificity when students referred to Roddy’s workshops, as in, “I’m in Roddy’s ‘Wednesday Group,’” said with a solemnity and import that went over my head. John Canfield eventually explained that the ‘Wednesday Group’ was the top tier of Roddy’s classes, accessible to those who had passed through the ‘Monday Group,’ or had demonstrated other markers of merit.

Though Roddy was not impervious to hierarchy – and he instinctively knew what he did and didn’t like – his mind could be changed. He was no particular fan of mine in the early years but, over time, I earned his respect. When he was editor of the Salt poetry list and wanted to open it to Americans, he asked me for ideas. (‘You know what I like,’ he said.) On my suggestion, he accepted Nuar Alsadir’s first collection, More Shadow Than Bird (2012), one of the gems of that list.

Kathleen Ossip

I met Roddy Lumsden in January 2002. We were slated to read together at the Ear Inn in Manhattan, part of their Saturday afternoon reading series. The streets in that part of west Soho were old and narrow, an interlocking puzzle of alleys. (Roddy, I learned later, loved puzzles and alleys.)

My first book had just won publication; his third, Roddy Lumsden is Dead, was newly out. He was definitely the headliner. I read from my book-to-be, including a series of loose sonnets whose titles all began with “My…” (‘My Ativan’, ‘My Best Self’). When Roddy got up to take the mike, he declared with surprise that he too had a series of sonnets in his new book, the titles of which all began with “My…” (‘My Pain’, ‘My Dark Side’). He read some of them. It struck me then as a possibly meaningful coincidence.

After the reading we talked for a bit and parted. That fall, after my book came out, I was “ego-surfing” (Roddy’s term for googling oneself) and came upon an interview where Roddy said he liked my book. My book publication prize came with a small travel grant. My mind drifted to giving a reading in London.

When I finally ran the idea by Roddy, he was as generous as… Roddy Lumsden. That is the most apt simile I can summon up. In no time, he had set up a mini-reading tour, including two readings in London, a reading in Oxford, and a class visit and reading in Cambridge with his friend and poet John Stammers.

Besides his unique and inarguably brilliant gifts as a poet, Roddy also had a gift for knowing poets, and knowing what they needed. When I came to London in 2003, I was introduced to Roddy’s ever-shifting and -expanding group of friends and current and former students-turned-friends. He was a master gatherer of poets and seemed to like nothing better than shooting the shit with them.

We discovered then that we were both interested, as the sonnets suggested, in expanding and complicating the confessional tradition. I called it, to myself, the Neo-Confessional. This was an approach not much in vogue at the time in the United States. With Roddy, I felt seen and heard in the best possible way. Another gift: He knew how to take a poet seriously. I sat in on one or two of his classes, and was struck by his frankness with his students (of the “this line is good” variety, suggesting that the rest could be discarded), which seemed to stem from his desire to take them seriously, to push them to be worthy of that attention.

We pursued a poetic correspondence via Facebook message, with Roddy always saying the right thing (not always the same as the comforting thing) about my anxieties about my work. I tried to reciprocate, but I wasn’t as eloquent as he was, and I had not thought as thoroughly as he had about poems.

Roddy was again generous when my second book came out, hosting me for another elaborate set of readings. He and Tim Wells took me to walk in the Bunhill Fields cemetery, where Blake is buried, on a gray October day. Then we repaired to Roddy’s home away from home, the Betsey Trotwood, where I met another huge crowd of his friends. He was so rich in friends.

When he became ill, and the illness turned very serious, I felt I had little use for a world that couldn’t keep him in it. I wrote him letters, sent him books and chocolate and a random five-pound note I found in my desk. I told him I had faith in his strength and his poetry to pull him through. That was all I could think of to do, and it hardly seems enough in the light, the real light, of all he did for me.

His unique and brilliant poetry will take me the rest of my life to get to the bottom of. Actually, I hope I never get there. Reading his poems is next best to being his friend, and it will have to do.

Rachael Allen

I was lucky enough to experience Roddy’s enormous capacity for kindness as a mentor when I was writing poems at an early stage. I am so grateful for his help and encouragement, and believe his influence on a generation of poets cannot be overstated.

Catherine Smith

Roddy Lumsden was an extraordinary poet, a gifted teacher and a kind man.

Diana Pooley

Roddy will be remembered with fondness and gratitude not only for his workshops but for the many, many poetry evening events in London he organised. We enjoyed and benefitted from it all.

There is much that I have had to thank him for personally. As well as for his workshops and readings he encouraged me to write and then edited my book of poems, Like This (Salt).

He will not be forgotten.

Simon Barraclough

The first time I met Roddy Lumsden was when he came along to a post-class gathering of Michael Donaghy’s poetry course at City University. I met a lot of special people through Michael and I met a lot of special people through Roddy.

The last time I saw Roddy was just before his illness, in the The Poetry Library, when he emerged from the shadow of one of the revolving stacks and fired off: “Simon, what’s your favourite opening line in poetry? It’s for a thing.” I was slightly taken aback but managed: “A brackish reach of shoal off Madaket”. I don’t know whether he approved or disapproved but I remember feeling that it was very important that he thought my offering passed muster.

Right now I imagine he’s organising complex and enjoyable multi-poet events on Earthly themes, “working on a thing,” and mingling with special people.

Matthew Caley

Roddy it was who coined the term ‘the pluralist now’ to describe the current poetry scene, and many of us thought of him as the Crew Junction of Poetry. As a point of eclectic inter-connection with virtually every tendency and strain of what poetry currently offered he was unsurpassed. He had that sharp, quizmaster memory and recall. He would be as utterly excited and praiseworthy of a tiny pamphlet from some [as yet] unheard American poet [and had probably already written quite a few poems ‘in reply’ to it] as by any well-known name. I also very much liked that in a poetry scene where people often stay tactically silent, he had opinions and expressed them. Every year or so I would meet up with him in Blackheath for a usually day-long one-to-one session and would plug into his knowledge-bank. This, with notes, and follow-up e-mails, would be enough to keep me going until the following year, or for several years, with fresh leads and trails to follow.

Once, visiting Roddy in hospital, we found him quite disorientated and speaking in a strangely dislocated way. Whether this was due to his condition, a change of medicinal routine or ‘ward-craziness’ or all three, we could not know. He looked urgently at us and said:

‘Are we going, then? We are going? Aren’t we? Are we going?’

Everyone was non-plussed and not sure how to reply. Eventually I said:

‘Where are we going, Roddy?”

‘The Polynesian Islands’

‘Why the Polynesian Islands, Roddy?’

‘Because there are so many lesbians’.

‘Why are there so many lesbians?’

‘Because of 1990’s pop music’.

‘Which 1990’s pop music, Roddy”

‘Don Paterson’.

It occurred to me that this was like doing one of Roddy’s quizzes but you already had the answer and had to guess what the question was.

At this juncture I could not help but burst out laughing. He looked right at me, into me, it seemed, and then burst out laughing joyously and unrestrainedly himself. [Not something I was used to him doing over many years of knowing him. He was witty and full of mischief but I rarely witnessed a full-on belly-laugh. ]. My rational side knew that this was an effect of his condition, not to see it as a proper exchange, but I could not help the feeling that it was a strange but joyous point of inter-connection. One I was very familiar with from his later work. I will continue to believe it.

There will be many appreciations and estimations of Roddy’s exceptional body of work. It is so pluralistic that there will be many differing takes. My own view is that he continually improved in those later works. Later works such as The Bells of Hope or Melt & Solve has something of that woozy, strange, dislocated sense our exchange had demonstrated. Certainly, as a poet, he wasn’t settling for any comfortable groove but pressing on, widening his reach and experimenting.

There was a coda to the hospital visit story.

Months later, settled into Manley Court, much more stable, the dislocation long gone, Roddy told me that he couldn’t remember much at all about that period. All I can remember, Matthew, he said, is that at one point I believed you were coming to take me to a house of ill-repute and were going to force me to partake of the services offered there. As I believed I had just married one of the ward nurses I was dead against this! That was his take. The Polynesian islands and 1990’s pop music had seemingly not even figured.

Finally, I could add that Roddy was instrumental in various good things happening for me in terms of the poetry world for which I am eternally grateful. But as almost three quarters of all poets in the UK might have a similar thing to say – it would hardly be an original take on matters.

What I will say is that Roddy, in person, in his work, was the pluralist now.

All love and support to his family.

Rest in peace, Roddy.

Andy Parkes

I met Roddy when I was first starting out in poetry – writing, frankly, terrible poems and running clinic’s early live reading and anthology series in New Cross. He was a huge presence in the poetry scene at the time – almost every poet we met seemed to trace their writing back to him. So when he became a regular face at our events, it felt like a real honour. But what soon became apparent was that it actually needn’t have felt that way – Roddy wasn’t deigning to come to our small events; he just truly and avowedly loved poetry, in all its forms, and worked tirelessly to expand his knowledge, discover new poets, and introduce writers to one other. He attended every event, read every book, and spoke to every poet he possibly could out of pure love for the work. It wasn’t long before he was suggesting readers to us and recommending other poets to get in touch, come to our events, and read our publications. In those early years, his support and encouragement was a huge part of any success we enjoyed in the poetry community. I will always look back very fondly on those times; upstairs in the Amersham Arms, Roddy leaning against the wall, listening intently to the next reader.

Jon Stone

I lived with Roddy for six months, a short while after we’d finished editing my debut collection. Having only really seen and spoken to him in the context of poetry gigs and editorial meetings at that point, I didn’t yet have a grasp on the extent to which every facet of his life was entangled with poetry. All events seemed to be conjured or endured for the sake of poetry, and poetry in turn seemed to flow into and fire all his friendships and fascinations. Everyone was his muse. I admired and envied the way he could simply sit down and start writing, so that conversations, frustrations, people and philosophy would be effortlessly braided into poems.

But these poems were also, very apparently, his primary means of talking, of sharing – intimate acts, rather than public stunts. Sometimes to my chagrin, this was also how he treated everyone else’s poems – as if they were private things, cautiously entrusted to him. This, I think, is what made him such a sensitive and yet bullish editor – he behaved at all times like a friend giving you tough advice on matters of the heart. That’s how I’ll remember him.

Ali Thurm

I first met Roddy at Morley College and was impressed by the way he included everyone, both young and old in his teaching. At the Poetry School he ran an inspiring workshop where we read mainly American contemporary poets, then he set mind-boggling homework based on all kinds of rules! He certainly made me think hard.

Roddy read his own poetry beautifully, with his soft lilting accent, and also encouraged me to give readings, which I was pretty scared to do. His relaxed events at the Betsy Trotwood were always warm, vibrant and entertaining.

It’s a tragedy that he died so young.

Ted Smith-Orr

Roddy treated poetry as a normal way of expressing oneself and a normal way of making a living. He is right.

Elizabeth Witts

I was lucky enough to go to Roddy’s Poetry classes when he was teaching at Morley College, and I really enjoyed the way he experimented with new verse forms, such as Dotted poems, Emergent poems, and Sevenlings (half the size of a sonnet). He was an inspiring tutor, gifted and encouraging.

Clare Pollard

When I arrived in London aged 21 and already a poet, one of the first people I met was Roddy Lumsden. I recognised him from the Poetry Review, so approached him with my usual youthful arrogance to say hello. He was definitely one of the cool gang, having recently been on the New Blood tour, with his poems full of pop-culture and ‘Tricks for the Barmaid’; his cute author photo. He knew the singer from the Divine Comedy, and had been poet-in-residence to the music industry, during which he had written that I was ‘The Britney Spears of poetry’. Soon he was introducing me to other poets, and I met people like Tim Wells, Tim Turnbull, Salena Godden, Nathan Penlington, Hugo Williams, Cheryl B, John Stammers. He was always a generous networker. He made you feel part of a scene.

By my thirties I was working as a freelance poet in London, often living hand to mouth, scrabbling together a living from readings, judging, editing, commissions and lots of night classes, and if I could be said to have a colleague, it was Roddy. He was impressed when I edited the UEA’s Reactions anthology of up-and-coming poets, and after that whenever we bumped into each-other we would swap the names of emerging poets like trading cards. He edited the Tall Lighthouse series, I co-edited Voice Recognition, he co-edited the Salt Book of Younger Poets, I was on the panel for the Faber New Poets and so on… He introduced me to Jay Bernard, Warsan Shire, Inua Ellams, Heather Phillipson, Sarah Howe, so many great poets. Between us, at one point, we seemed to be teaching almost every poetry class in London and when we met over the photocopier it was always the same question: so, who’s good in this class? Some poets make it, then feel threatened by those coming up behind, but Roddy never did. He just loved it, that moment when a poet finds their voice and you can see them taking off. Every year he organised Eric Gregory readings for example, for free, just because he wanted to.

Sometimes after our classes at the Poetry School everyone would go for a pint in The Pineapple. Those were good nights. He was such a gossip. I was actually quite careful what I said in front of him in the end, but that’s hypocritical because I absolutely relished all the poetry gossip he would share with me. I remember all those massive themed readings he did too, where fifty poets would all write poems based on folktales or Carry On Films or something. And the Christmas shindigs he organised at the Betsy Trotwood with Tim Wells, where he’d do a fiendishly difficult poetry quiz. In the end he also helped found the Poetry School / University of Newcastle MA, and I was honoured he asked me to teach it with him. He introduced me to so many amazing American poets through that course, and he always did great stuff on inventing forms – he invented so many himself, like the sevenling and the overlay. I didn’t know much about Roddy’s life outside poetry, but then I wasn’t always sure it existed. I don’t think I’ve ever known anyone who loved poetry so much.

Rebecca Tamás

I very much doubt I would be the poet I am without Roddy. I first met him at an event at Edinburgh university where I was studying. He generously and un-ostentatiously said that if I ever moved to London, I should join his evening poetry group. I did this the year after, and began to develop my skill as a poet through his thoughtful guidance, and that of the many, many new friends I met there. Roddy edited my first pamphlet for Salt, and it meant a huge amount that he would put his trust in my work in that way. It was the beginning of me writing the poetry I truly wanted to write.

It’s easy for people to think that somehow we can become writers in the world through the sheer pressure of our own talent. This is simply not the case. As poets, we grow through the community, support and trust of our fellow writers. Roddy helped me grow in that way. He was a complicated, many layered person, one who was truly committed to using his own talent and voice to bring up others. He will be sorely missed by his friends, and by the entire poetry community of readers and writers, for whom he did so much.

Ian Duhig

The poem below was written for an earlier informal gathering when Roddy became very ill. Apart from this, I did once get a chance to seriously tell him how important I thought his work was in promoting a new generation of poets. He shrugged it off, needless to mention.

Forms

for Roddy Lumsden

This hare came with other forms.

Opened, it was light in his hands,

the colour of its paper or silence.

It hid well there in its winter coat,

but he knew this was a creature

legendary for its uncleanliness,

able to change sex every year,

invent new forms of intercourse,

bend the moon’s fertility to its will.

So he fed it night and shadows

until others could see its prints,

its stained sheets, its true purity.

He did this as a lover and a poet,

because it was his nature to share

as the hare’s to write its own love

in white ink on the snow, invisibly

but always there, for you, for him,

a page waiting the fall of darkness.

Richard O’Brien

The first Roddy Lumsden poem I loved was ‘History’. He rhymes ‘you’re using words like claymore, context, coracle’ with ‘minor crises turning into miracles’ and that, alongside the playful rug-pulling of the realisation that ‘only one of us is leaving tracks behind’, is exactly what I loved about the work of his that most connected with me – the sudden surprising shifts in tone and thought coupled with beautiful, subtle threads of sound. When I messaged him about it, when we’d first started speaking back in 2007 (!) he wrote ‘not a personal favourite – a bit too much of an ethnologist’s jibe at political history, though I still agree with the sentiment.’ Twelve years later I barely know what this means, but there’s something that feels very Roddy about it – at the time I just remember thinking that I was in contact with a writer who knew more about more things, on a higher level, than I could ever hope to, and that if one day I could ever be in the position to send a message like that with such assuredness, that would be something like ‘making it as a poet.’

I’m sure a lot of you who knew him will recognise the Roddiness of the sentence: the breadth of reading and thinking, the self-effacement, and the contrariness it speaks to. I vaguely remember him saying, when he was judging some kind of award, that he was reading through two poetry collections every day, and in retrospect I feel like the number could have been higher – that feels like what he would be doing anyway, any given Sunday. The time I saw most of him was around 2007-2011, when he edited my pamphlet and the Salt Book of Younger Poets. Even though I didn’t know him hugely well the last few years, I can’t think of a single person who has directly helped, influenced, and guided the writing and the careers of more poets I know in this country. I think something like 70% of the books on my shelves by British writers under 40 were written under some kind of mentorship, direct or indirect, from Roddy Lumsden, and I feel like that legacy is felt across a whole generation. I hope he knew how respected, admired, and loved he was – how much gratitude a community of writers felt and continue to feel towards him. Rest in peace, Roddy. We were very lucky to have you.

Fran Lock

Whenever I talk about Roddy and his influence on my life and writing, I tell the following story in the following way: remember that bit in Frankenstein where the eponymous hero rocks up at the University of Ingolstadt expecting to wow his professors with his arcane reading habits? And remember how one particularly underwhelmed prof takes him to task for wasting his time on out-dated rubbish like Paracelsus while ignoring this amazing wealth of contemporary scientific research? That was basically me and Roddy, meeting for the first time during the final year of my MA.

And typically I’ll go on to talk about how lucky I was to be mentored by Roddy, how he broadened my horizons, took me seriously enough as a writer to trust me with criticism – oh, so much thoroughly, pulverizingly blunt criticism – and gave me a vocabulary for talking about my own work with other poets. All of which is completely true without being even the half of it.

For the longest time I thought I thought Roddy didn’t like me. He never gave much away, and he wasn’t given to needless effusions. He let nothing slide either. He was the absolute scourge of cheap sentiment, gnomic vagary, cliché, purple language, and the tendency to hide nothingy or confusing statements behind a plausible musicality. I was guilty of all these crimes, so he kept picking me up for them. When I used a phrase or an image that didn’t seem to be working, he asked me explain it. And to begin with this felt like a mercilessly interrogative process. I used to go home and swear, or kick the couch, but I wrote it out again, and again, and again. Until one day something just clicked, I got it: Roddy wasn’t ‘picking on’ me because he disliked me. He was pushing me to write better because he cared about poetry, and because he believed in my work and wanted me to do better. I was listening to him because I cared about poetry too. This wasn’t an adversarial relationship, this was The Work, this was what it looked and felt like, always would if I was going to produce anything of value. I was learning about refining my craft, about being a perceptive reader and a clear-sighted editor. And as the draft for what would eventually become The Mystic and the Pig Thief began to take shape, I knew that the first gift Roddy had given me was the ability to write in a way that did justice to the people and places I’d loved.

This in itself is immeasurable. I still live by the lessons he taught me; I apply them to my own students in my own teaching and editing: read widely, read outside of your comfort zones, and when you write make sure that every line is transmitting tension, intension and meaning, make it richer, make it stranger, but anchor it, justify it; a poem isn’t a monument to your own ego, it’s not about showing off how clever you are or how many big words you know, a poem is a house, it needs to be structurally sound, you want other people to enter, to move around inside. It’s not just on the page, it’s of the world. It should bear the traces of that world. On a purely practical level, Roddy the teacher, Roddy the mentor, gave me the tools not only to make my own writing better, but to teach others in turn, to help nurture burgeoning talents, to be a link in the chain.

But that isn’t the whole story. Roddy and I didn’t reconnect, didn’t become friends until a year after my MA finished. I was still a bit in awe of him to be honest, and I’d pretty much shrunk back into my shell after graduation. When I did finally reach out I did so because I was drowning. Depression is a kick in the head and it was eating me alive. I knew if I didn’t do something to dig myself out of the pit I was in, I wasn’t climbing out. I was still hawking my stuff at open mics but it wasn’t really going anywhere. It didn’t do much for me, on a personal or a professional level. Poetry’s one of the few things that has had consistent sweetness and meaning for me, but it was starting to feel blanched, bled out and pointless. I needed something else. So I messaged Roddy, and I asked if he knew of any readings or groups I could go to or join, just to be doing something with my writing, so I could do the work that actually mattered and made sense to me, so I could feel like I existed. And Roddy threw me a lifeline. He didn’t have to do that. He could have ignored me, or fobbed me off, but he didn’t. He let me come to his classes at Poetry School. He did his best to connect me to other people, to the wider writing world. Which might not sound like much, but I promise, it was asking a lot. I’m not good with humans, and including and involving me in anything, and then persisting in that endeavour was effort. I know also that I didn’t always appear the most grateful for that, but I think – I hope – Roddy did understand how much it meant to me, and what it did for me, having that outlet, a place where I could go to just talk about poetry, the space to think and make. I learnt so much there, not just from Roddy, but from the other poets in the group. And I was introduced to work by writers who became instrumental in developing my own approach to poetry. During this period I also got to know Roddy as a person. He stopped being this All Powerful Oz figure to me and became someone I could connect with over obscure new-wave and post-punk music, outsider art, anomalous phenomena, the general crumminess of life. We shared a passion for odd words and lexicons, for bits of cultural ephemera and fragments of weird lore. My friend Sarah wrote to me recently describing Roddy’s ‘utterly eccentric gift with people’. This is so true. I learnt to like and admire him not just as a writer but as somebody who was so totally and utterly himself. I think we came to understand each other, a bit anyway, because for our very different reasons neither of us had ever felt truly comfortable in our own skins, or at home in the world. Roddy taught me also that this was okay. It didn’t always feel marvellous, and most people wouldn’t like it, but sod those people, we could write.

Poetry isn’t really a very kind or forgiving place, and there have been many occasions where I’ve come close to giving up. I was close to giving up when Roddy convinced Salt to publish Mystic and the Pig Thief. It meant the world to me, having that book out, and that was all Roddy. I was Salt’s last single author collection, and I had the very strong feeling they weren’t that keen, but Roddy persuaded them, they did it as a favour to him. And it is still the collection I’m most proud of – most glad about; the launch event is still one of my happiest poetry-related memories, and I still treasure the time Roddy and I spent editing and revising the manuscript.

Roddy supported, encouraged and championed my work. He did this for a lot of people. I have never met anyone, and I doubt I ever will, who was so selfless and so tireless in the nurturing and promotion of poetry he believed in, and in trying to build us up as a community or cohort. It’s amazing, what he achieved, the sheer extent of what all of us owe him, but that’s not what I’m going to miss. I’m going to miss our conversations. I’m going to miss being a receptacle for his “poetry goss”, and his look of long-suffering perplexity when I showed him the nine-hundred and fifth photo of my dog. I’m going to miss how when we met and reported back to each other from our different worlds, there’d always be something that stuck: a phrase or an anecdote, a reading recommendation, something that fuelled the poetry, or made me laugh, or caused me to think more deeply about something I’d have otherwise dismissed. I’m going to miss the odd text messages out of the blue: Read this, thought of you… Remember Crispy Ambulance..? Is there such a thing as a remedial dog…?

I have such good clear lasting memories of Roddy, and I’m very grateful for that. My best is Roddy at the Betsey in 2017 for the celebration (as opposed to an actual launch) of So Glad I’m Me. It was special, both to hear Roddy read, in the world after such a long illness, and to see him surrounded by his poetry family. Poetry Paterfamilias was my nickname for him, and it’s true, he was. We shared coffee that evening, and my brother performed card tricks on him; we talked about being ‘aspy’, and about Roddy’s T.S.E nomination. It was kind of beautiful. And I know I’m not really part of that poetry family, or if I am, I’m a far-flung crooked branch of the tree that should probably be lopped off to prevent the spread of infectious fungus… That’s not the point. I was happy that Roddy had a poetry family, that so many people cared – still care. It’s a testament to the kind of person he was. I’ll keep that evening with me always.

Ros Barber

Roddy was instrumental in my getting my first collection published by Anvil (and given the state of poetry publishing then, perhaps getting published at all). As co-editor (with Hamish Ironside) of the Anvil New Poets 3 anthology, Roddy selected me to be one of the ten new voices featured. I shall never forget receiving that call from him in the kitchen of my old flat; he was extremely complimentary about my work at a time when I really needed the boost. Thanks to him selecting me for the anthology, I was able to get my debut and second collections published with Anvil. Like many poets working in the UK today, I owe him a great deal.

Becky Varley-Winter

I first met Roddy at Sarah Howe’s debut pamphlet launch, soon after he’d published Third Wish Wasted. He gave me a copy of it, said he would read some of my work, and didn’t ask for anything in return. I see now that he could definitely have charged me for mentoring, yet he never did; he was generous in that way. I wasn’t his student, but he invited me to write new poems for events he ran at the Betsey Trotwood, which were always varied and exciting. Despite this, I assumed that he didn’t think anything of my work, then he wrote me a poem in his Fifty Poems for Fifty Poets which stunned me with its kindness. After he got ill we met for lunch, and he insisted on paying, even though he was living in a care home by then. We had become friends, though there were aspects of him I couldn’t always understand; he was contrary and spiky and gossipy and contemplative by turns. He liked the silvery backlit quality of the sky at dusk, and told me a word for it, which I have since forgotten. Once I told him about playing in an orchestra as a teenager, and drifting asleep on the warm, vibrating skin of a timpani drum. “That’s a poem,” he said. The last time I saw him, in summer 2019, I said I wasn’t sure whether to drop by, as he’d stopped responding to messages. “You’re always welcome here,” he replied. He also commented how strange it was not to have more to do; he was so used to teaching, editing, and mentoring. This welcoming and hardworking ethos seemed to sum up his approach to writing. He was blunt and uncompromising, really cared about poetry, and lived it. Poems and friendships spilled into each other, and his feelings came through in his work, which showed me in its own way that poetry is no stranger to life. I am thankful for all he did for me, for his presence, his spiky warmth, and his unostentatious encouragement of a whole poetry scene.

Judy Brown

I’m so grateful for so many of the things that Roddy did. It’s hard to get your head round how influential he was for so many poets – impossible to imagine how things would have been without him.

Roddy knew so many poems and so many people (and so many other things too), and seemed to have time and thought for everyone he taught. His poems are like no one else’s. I first went to his class at City University, and then at the Poetry School. I met most of the poets I know through that class, read many books I wouldn’t have known about otherwise, and wrote with more confidence and more self-criticism and more sense of the possibilities of poetry than would ever have been possible without Roddy’s vast knowledge, talent and considerable kindness.

Cath Drake

Roddy – You’ve done so much for poetry and for the development of the work of many, including my own poetry. One of the most memorable moments for me was your fabulous reading of new work at my pamphlet launch several years ago. The poetry community will not be the same without you. Your memory, your wit with words, your presence at our readings and parties will live on in our memories and, of course in the wonderful poetry you’ve left us with. You are sorely missed. Love and gratitude.

Sarah Wedderburn

Working with Roddy was one of the privileges of my life. He gave me the confidence to develop, grow and share my work. He was a beautiful poet, and as a teacher he was unique. He had a gimlet eye, a pitch-perfect ear, and he was an opener-up of worlds. His group was fun and exhilarating, and serious in the way that play, at its best, always is. He attracted brilliant, lovely poets. I learned so much in his and their company. I miss him very much.

Not asleep

for RL

The house sleeps, the puppy dreaming in her crate,

the spoons hung loosely from their hooks,

and those mounds are people, their breath

recycling air so the room is full of human.

Strange, this surrender—I lie awake,

searching beyond walls to robins sleeping,

sparrows in the holly, ponies on the hill, their heads

hung low, dozing in chilly moonlight. Life subdued

waits for the earth to roll the sun up, stir the wren,

prompt buzz and song, the amble of first steps.

My friend, tonight your sleep has been forbidden—

a gloved hand raised, a no-through-road to morning.

My vigil is for you, poet, now night’s slow inspiration

is lost. When you died, you did not fall asleep.

Claire Booker

Roddy was my very first experience of a poetry workshop leader when, some years back, I attended six sessions of working towards a collection. He was inspirational, and very kind to me (I was the least experienced in the group), stepping in with helpful suggestions and encouragement. His own poetry was a revelation, and I can only say that his was a brilliant introduction to exploring one’s own voice. He was modest, dryly humorous, and generous in the attention he gave us. I’m so very sorry that his life was cut short. His poetry will live on.

Jane Speare

I was shocked to find out that Roddy has died. I went to two of his summer schools at Morley College and then a class at the Poetry School between 2008-2012. I loved his classes and will always remember him intensely focused with a can of coke by his side at 10am ready to argue about something like the power of the full stop or introduce some really left field adventurous writing. His classes were captivating and I enjoyed bumping into and chatting with him several times in the Waterloo area. Along with other fantastic poets I met at Morley and the Poetry School Roddy is a chief reason I am working on a Phd researching how adolescents construct personal meanings with poetry.

Mary Muir

He opened a whole new world for me in Lambeth. My fondly signed copies of Terrific Melancholy and Mischief Night so well thumbed. He got you to write a poem every time you go in the door/up the stairs/have a shower. Great Poet. Great Teacher.

Katrina Naomi

Roddy taught me so much. I attended his weekly classes at the City Uni in London a long time back. He helped me put The Girl with the Cactus Handshake, my first collection, together and gave me a great quote to go on the back. I was still a rather new and inexperienced poet and I was then and remain now, hugely grateful to him for all of his help. As it happens, I’d written a poem in my forthcoming collection Wild Persistence and dedicated it to him before I knew of his death. He was a wonderful tutor and a highly stylish and inventive poet. He’s going to be missed massively.

John McCullough

Roddy was my editor at Salt and we shared a love of strange facts. Below is my poem from Reckless Paper Birds where Roddy Lumsden and I have an imaginary son together who is also trivia obsessed.

A Walk with Our Imaginary Son

for Roddy Lumsden

Rhinoceros vase, bubble turnip, wedding cake venus.

Yes, he is definitely our son, rattling off seashells

between anecdotes from a year well-spent at uni –

his first bar job, first spliff and lots of things

I never did with girls. We’ve met him in Pavilion Gardens

to show him punks and jugglers, his wild inheritance.

Pavilion, from the Latin papilio, moth or butterfly,

and, later, a tent with two flaps, a word fluttering

who knows where. The grass today is full of legs

that might escape their owners, long beings

that reach for each other. The trees, too, are a photograph

of a party – frozen small talk and sneezing and tears

of laughter as we walk through their shadows

and he lists the names: lime, Dutch elm, plane.

I study his face, the nose I saddled him with,

the cryptic Lumsden eyes, a moon-sized laugh.

Did you know every shadow has a negative weight?

No I didn’t, I say, but I can well believe it, reminded loosely

of how a moth feels on my hand, how there are no words

for the difference it makes to have him here, how we’ve built

a special tent and now it’s flying. But the evening approaches.

We don’t want him to miss his train. This circuit of the park

will be the last. We slow our pace and watch

the shadows advancing from our feet, certain things

with philosophies, dominions; nothing like moths.

Nick Makoha

Roddy Lumsden was a poet who did not see colour he saw talent. His encouragement over the years was truly beneficial. Often he asked to see my written work and came to performances. I remember his Monopoly poetry event at The Betsey Trotwood that he would hold in the summer. The last one I was able to attend was in 2009. My slot was Bow St. That was always a good place to meet some other best contemporary poets. He will be missed.

Andy Brown

I first met Roddy when I was Centre Director at Totleigh Barton for the Arvon Foundation. Must have been 1999 or 2000 I think. He was co-tutoring a course and arrived on the Monday afternoon in a taxi, carrying nothing with him but the clothes on his back and what he had in his pockets… he had lost his luggage on the train and it wouldn’t be delivered or collectable from the train company for a few days. This meant we had to go clothes shopping immediately.

Bundling him in to the car we went back to the nearest town, Okehampton, and found a clothes outlet. A really cheap clothes outlet. It felt odd standing there with someone I barely knew watching them choose clothes… Roddy opted for some jeans with one of those elasticated belts, a couple of cheap t-shirts with logos on the front, and some kind of sweater that you wouldn’t want to wear standing close to a naked flame. None of it seemed to fit him very well. “No point in splashing out,” he said, or words to that effect, “my luggage will be here in a few days.”

Back at Totleigh Barton he went around for the week looking like he was wearing a kid brother’s wardrobe. When he gave a reading on the Tuesday night he still didn’t look entirely himself, even though at that stage I didn’t really know what ‘entirely himself’ was for Roddy.

It was a memorable start to a friendship that included more tutoring over the years, meeting up at Poetry events, and Roddy championing my work in magazines and anthologies, as well as editing my books at Salt. Something he effected with skill and generosity and great enthusiasm, for which I am very very grateful. I always wanted to tease him about the clothes, but never really got the chance to do so, and now that chance has sadly gone.

I can’t remember if the luggage ever did turn up.

In my mind he’s still not quite himself in someone else’s clothes.

Lavinia Singer

Here is a poem I’d written for Roddy when he became seriously unwell, in response to one he had written me.

Charm’d: the opiate rod

for Roddy Lumsden

water witching

the locked ground

lightning

spear cast broadly

Napier’s bones

in a wrecked world

from steep air angled

saltire cross

a house falls to the sea

reck this

Arcadian pipe

stones spiced red

rare fruit

in armour crowned

the staff is steady

spawning

when it connects, –

conducts

Barbara Barnes

I was in Roddy’s Wednesday group for years. I miss him a great deal.

We take the Jitney Trail, Tatamagouche, Nova Scotia

for Roddy

Because once you told me you wanted to write it,

we walk it, as dawn becomes an open doorway.

Your pen had rolled beyond arm’s reach, marooned

beneath desk, behind walls– a spent ghost in dust.

Haunted by nightshifts, you blink to steady.

We track the better route, follow path and scent.

This limb of land torn from your origins, roughly cut

by time and ice, light carving us a silence we move in.

Your burr softens bugleweed, sweet gale, greenbrier,

stonecrop, names a spot to stop the day’s trudge.

River John winds, holds us in a loose embrace. Resting,

you scout a black bird, another, then altogether three.

Niall Campbell

I met Roddy in St Andrews in 2009 – he was there for Stanza and introducing his ‘pilots’. I remember being caught offguard when he asked to see poems and then quickly gave feedback. My early experiences of poets and poetry had been of people with little time and often little interest in other people’s work. And then there was Roddy – always supporting, encouraging and celebrating. He set an example – he gave his time and his energy. I’ll always be thankful for what he did.

Angela Cleland

I first met Roddy at a night called Shortfuse in London, in the poets’ natural habitat, the top room of a pub. From the very beginning he took me seriously as a poet and his belief in my work helped me immeasurably over the years. Roddy was a generous spirit and there was never any sense that he wanted anything from you other than to include you in his poetry world, and he found and included so many of us.

Roddy and I shared a love of Norman MacCaig. I remember talking about MacCaig’s poetry in the pub, me struggling to remember the titles of the poems I love, and him reeling off lines from his favourites as if they were just there all around him waiting to be plucked out of the air. Roddy spoke about knowing MacCaig and told stories about things the great man had said to him in another time, in another pub. I was jealous and in awe that he’d known him. Of course, I should have been counting my lucky stars that I was sitting there with Roddy Lumsden, knowing him well enough to take for granted.

The poetry Roddy has left behind is a gift, though we’d rather still have the man. I’m so glad to have known him.

Alison Winch

Roddy had a gift for bringing poets together – through his classes, at events or in books. Some of the poems in my collection were workshopped in his classes and I am so grateful for both his input and also from the other poets in the room who had come together through him.

Mel Pryor

Roddy Lumsden was a total one-off, a brilliant and warm and generous tutor, a magnificent poet, a magical person, a total honey, it’s incomprehensible that he’s gone. Thank goodness his poems live on. And what poems! God bless Roddy Lumsden.

Geraldine Stoneham

I met Roddy at a Poetry School workshop in Birmingham and felt very much at home with his way of discussing poetry. I later attended a few of his classes in London and read at one of his events. It was the first time I felt that I could just relax and write the kind of poems that came naturally, rather than trying to work out the ‘rules’. He even encouraged me to unpick edits I’d previously made to my poems while trying to regularise them, and gave me publishing advice. I was thrilled when he picked out two of my poems anonymously in competitions he was judging. Although I didn’t know him well, I treasured the small contact we had, and some of my poems were written for him. May he be walking a joyful and fascinating path of light now. Thank you, Roddy.

Camellia Stafford

One late night, after a poetry thing, a few poets, including Amy Key, Roddy and me, elapsed to a dark and grainy bar with a dance floor off Old Street. We sat on a battered leather couch at the edge of the empty disco sharing a packet of crisps. Suddenly, Roddy held up in wonderment and with some incredulity, a heart-shaped crisp that he seemed to have found by magic. Amy and I were enthralled. A discussion ensued about who should get to keep the heart-shaped crisp. (I can’t remember the outcome so I hope it wasn’t me). Today, I recalled the heart-shaped crisp for the first time in years and the memory of that moment slid achingly through my heart. The heart-shaped crisp is like an emblem of the friendship Amy, Roddy and I shared, especially in those giddy, early days of attending Roddy’s classes when it was so often more about what happened after class…

I will always miss Roddy. He is a tremendously important part of my life in many different ways. He encouraged and supported me with my writing with such acute understanding and sensitivity towards my poems. Without him, I’m really not sure that I would have ever had my pamphlet and poetry collection published. He gave me the self-belief, the push and the opportunities to take my poetry from the classroom to publication. In recent years I have missed, and will continue to miss, his mentorship. But, above all else, Roddy is my cherished friend. We understood each other’s natures instinctively and so I felt, somehow, safe with Roddy. Also, we made each other laugh, really laugh, sometimes to tears, sharing a silly sort of quirky, crazy sense of humour. The verse-play that Roddy and I wrote and performed together in the characters of Penny and Jeff, at the launch of Roddy’s collection ‘Melt and Solve’, sprang from that sense of humour. Jeff, a part-time fashion photographer who lived in a skip, possessed a pair of toenail clippers he had fashioned from a turkey wishbone. Only Roddy could have come up with that. During his illness, I spent many hours with him on the phone and I got to know things I’d not known about him before. I’m thankful for all those conversations I had with Roddy and since he died, I’ve felt like I’m still trying to carry on a conversation with him.

Ben Wilkinson

Roddy was my first editor. With tall-lighthouse publisher Les Robinson, his Pilot scheme would platform sixteen new voices under 30 in pamphlet form in the late 00s; voices that would in some cases prove defining, including Emily Berry, Adam O’Riordan and Sarah Howe. The main thing that struck me from the off was Roddy’s unwavering honesty: online, but also (and I seriously admired this) in person. In matters of poetry, he would always tell you more or less exactly what he thought; a refreshing trait in this world of schmoozers and networkers. He once told a room full of other poets at the London launch of my pamphlet that my work was well crafted and had required very little editing; as a twenty-two-year-old no doubt looking for approval from literary elders, I was made up. Then a couple of years later, at the launch of a generational anthology he edited, I mentioned a poem of mine from the book had featured in a national paper, and he simply commented that they might have chosen a better one. You could take that as hurtful, even spiteful, but whichever way you diagnose, I honestly think that Roddy was just given to speaking his mind. He loved the poetry that he loved, but was equally unafraid to call out the mediocre or second-rate as he found it, even when it was the work of established voices and influencers. I always enjoyed talking with him about the voices of the day on the handful of occasions that I had the chance, and in forums online (remember those?). His own excellent poetry never quite enjoyed the acclaim it likely deserved; a lesson to us all, perhaps. Though he helped to shape my generation of poets through enthusiasm and mentorship, Roddy never really reviewed; odd, then, that I should count him as one of the folks who made me want to stick with writing criticism in those early years. I struggle to think of many people who care about poems in the way he did. He lived poetry, and poetry in these isles will be the poorer without him.

Yvonne Green

Roddy was 11 years my junior but I read him long before I stopped writing for the drawer. He sat at a table opposite mine at a B&B once, afraid to disturb him and unable to hold back, I managed to wait until he’d almost finished eating before going over. He seemed shy but at the same time he totally shifted his focus to me, made me feel affirmed, relaxed, I can’t remember what he said but I remember his forehead dipping, and the effort he put into the exchange, eye contact, connection and space created. Being that close to his palpable intelligence, kindness and open sensitivity made me feel part of something authentic.

His works forms/outlets/protégées are a remarkable legacy.

If you have any memories of Roddy that you’d like us to share here, please get in touch at [email protected].

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.