One of the hardest things for boys to learn is that a teacher is human. One of the hardest things for a teacher to learn is not to try and tell them.

(‘The History Boys’)

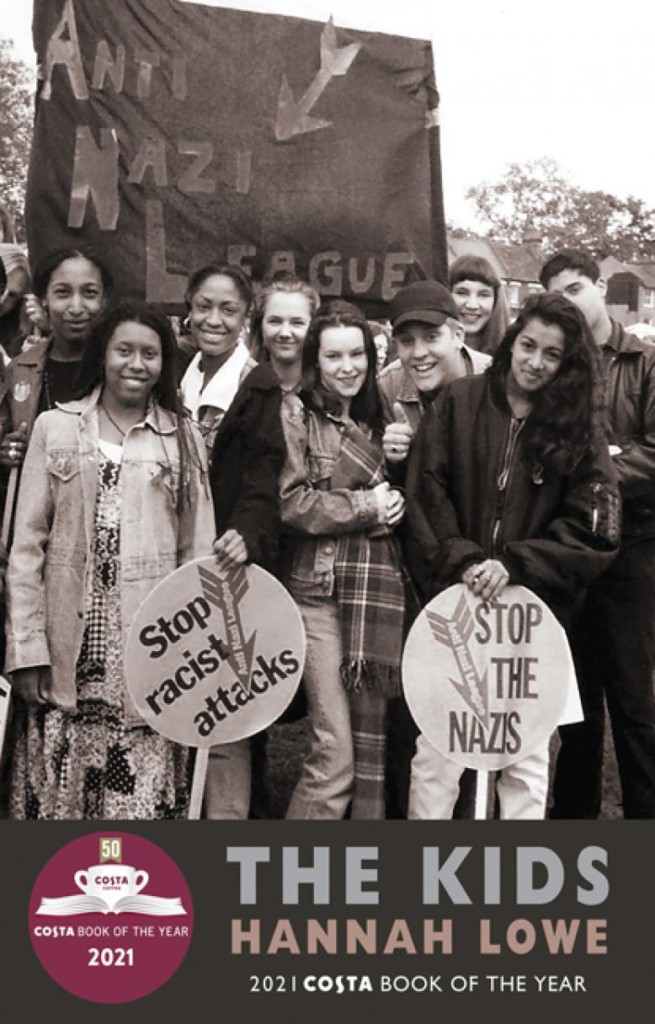

Hannah Lowe could have aptly taken her epigraph for The Kids (Bloodaxe) from Alan Bennett’s History teacher, Hector. In Bennett’s play, Hector’s pushing of teacher-student boundaries makes him charismatic and problematic in equal parts. Lowe’s latest collection provides a striking testament to his dictum.

The book begins with the abrupt death of the speaker’s father. Though the event, which aligns with Lowe’s own biographical experience, is expressed bluntly (‘My father was dead’), it is deeply felt, and one needn’t look far to learn of its appreciable impact on the course of Lowe’s life. She has elsewhere spoken of how her parents’ deaths triggered her impulse to write poems, where her first collection, Chick, explored the complex relationship with her half-absent, gambling father. By the end of this opening poem, the loss of her father has prompted a profound moment of introspection: ‘Now what should I do?’. These five dramatic monosyllables are no doubt an echo of Rilke’s famous line; indeed, Lowe’s question is well answered by it: ‘You must change your life’. This is exactly what the speaker does, moving from the drudgery of office work (‘typing, filing, typing’) to the dynamic world of teaching, which provides the setting and subject for the collection.

Questions are more characteristic of Lowe’s narrator-teacher than answers. Often, they open a sonnet with a rhetorical flourish (‘Why would anyone want to do again / the thing they’d failed?’ (‘Try, Try, Try Again’), or ‘Why did no one warn me about Monique –’ (‘Queen Bee’)). But the collection’s first section – which sees our narrator in the role of teacher – uses them just as often to close sonnets, repeatedly wondering ‘what happened’ to former students and classmates (‘Simile’). Unlike the finality of a Shakespearean rhyming couplet, Lowe’s sonnets – which all of these poems are, bar one – are as full of uncertainty in their fourteenth line as their first. Their parting words serve to gesture beyond themselves, and beyond the limits of teachers’ knowledge.

It seems that Lowe was making a conscious effort to explore these territories. In a recent interview for The Guardian, she spoke of ‘trying to destabilise that relationship between the teacher and student – the idea of the teacher being the figure with knowledge to impart, and the student as the passive receptacle’ and noted, ‘It was never like that in the classroom for me’. Accordingly, the flawed knowledge of Lowe’s teacher is exposed in several ways. When hauled up by one of the ‘posh girls’ for an embarrassing faux pas, she is hyper-aware of the role reversal engendered by the moment (‘as if I were the girl / and she the teacher’) and mulishly refuses to accept the correction (‘Pepys’). In ‘Sonnet for the A Level English Literature and Language Poetry Syllabus’, she questions the legitimacy of teaching literature itself. Teaching the A Level Poetry Syllabus is ‘breaking the poems apart, slapping / their parts to the board –’; later, she reflects that her neatly filed notes give the false impression that:

you could catch and wrap

a poem, what you thought and felt about it,

under plastic – flattened, silenced, trapped.(‘Sonnet for the Punched Pocket’)

Here, the vitality of poetry is positively stifled by its inclusion in the curriculum. I was reminded of the gorgeously impossible exam question of Carol Ann Duffy’s ‘Mrs. Schofield’s GCSE’:

Explain how poetry

pursues the human like the smitten moon

above the weeping, laughing earth; how we

make prayers of it.

Such alchemy, of course, cannot be explained. To admit this is testament to the sensitivity of Lowe’s teacher, as well as succinct encapsulation of the job’s frustrations.

Other, more worldly factors affect teaching too. As the first section continues, social realities – including the shadows of Britain’s imperial past and insidiously racialised political rhetoric – encroach on the educational sphere of students and teachers alike. In ‘The Only English Kid’, we watch with trepidation the ‘guilty’ silence of a young English white boy hearing his classmates’ experiences of racism and witness, in ‘Ricochet’, how such attitudes become part of mainstream narratives after the 7/7 bombing: ‘The papers called the bombers British-born.’

Political narratives aside, human beings come with their own personal histories. Lowe’s teacher is a grieving person, who sneaks to the stockroom to ‘bite [her] hand to keep / from crying’ (‘Red-handed’), who stoically ‘tuck[s] away [her] numb heart in an ice-pack’ in order to continue the unceasing work of teaching (‘Something Sweet’). Conversely, several of her students’ lives seem far beyond their years, often poignantly so: a powerful string of epithets in ‘The Unretained’ tells us of ‘utterly stoned’ Luke, Amal ‘who slept on strangers’ sofas’, and Martha ‘five-months-pregnant’. Such blurring of boundaries prepares the ground for the collection’s most daring poems, which explore the taboo subject of student-teacher attraction. There is a slight, shocking jolt that comes from reading of a ‘half-boy, / half-man’ student seen to ‘ignite a little flame’ (‘Boy’), or from the narrator imagining ‘trouble, / desire, bliss’ after bumping into an alumnus (‘Sonnet for Darren’). Attraction is, it is important to note, the key term, and is significantly different from action. A further point to keep in mind is that of the author-speaker distinction, where the poems are working to present ways into these challenging (but common) experiences, rather than necessarily reporting real experience from the author’s own life. As Lowe has made clear in The Guardian, ‘No lines were crossed, no code broken’. Yet the poems’ strength lies in their ability to articulate the vivid, sensual impression of a possibility. The fluidity of teacher-student roles in the first section is picked up by a complete role reversal in the second, in which we meet our narrator as student and teacher’s daughter. These poems chronicle teachers’ behaviours from the inspiring (‘With her, I learnt what learning was for’ (‘Étudier’)) to the downright cruel (‘why […] / did Mr Presley take his scissors, and raise / my plait to its jaws?’ (‘Mr Presley’)). This section is notable for containing the book’s only non-sonnet, a skilful longer poem which details the effect of a fatal stroke suffered by the narrator’s mother on the narrator’s own identity:

And when she looked at me

I was teacher now, and mother.(‘The Stroke’)

The similarities between these two roles are brought into sharp relief by the book’s final section, which characterise both as intense, self-occluding caring roles. When our narrator urges herself to ‘Hold back the tears’ after a bad date (‘Zoom’), we are reminded of the teacher doing the same in the stockroom. But in the end, it is a yoga class that provides the perfect metaphor for Lowe’s ongoing aesthetics of education, now realised in her role as Creative Writing Lecturer at Brunel. As she watches her yoga teacher being taught, she reflects on her experiences of leading poetry ‘masterclasses’ and comes to understand something fundamental to her own practice:

But I’m not a master, just a pair of palms

which push or pull or loosen someone’s lines –

I still need kind and guiding hands on mine(‘Kathy, Carla’)

These closing lines strike at the heart of what this collection can afford us: a view of the teacher not as all-knowing, invulnerable educational authority, but as perpetual student and something altogether more human. After reading the formally skilled, humorous and compassionate poems of this collection, we would have good reason to doubt Lowe’s own assessment of her poetic mastery.

The Kids by Hannah Lowe. You can buy the book here.

Tanvi Roberts writes poems, essays and reviews. Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in Poetry Ireland Review, The Moth, Trumpet, and Rattle. Her critical work has appeared in the Irish Times, the Dublin Review of Books, and Poetry Ireland Review.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.