Sean Wai Keung’s debut collection sikfan glaschu begins with the disclaimer that its poems ‘should not be taken as reviews – nor should the quality of the poems necessarily be seen to reflect on the quality of any food or place which may bear a similar name’. However, this generous sentiment feels a tad ironic since many poems, each titled after an assortment of restaurants in Glasgow, do lean into various forms of food writing. Some poems read like online customer reviews: ‘seriously though / this place is so fucking delicious you have to give it a try just trust me’ (‘kurdish street food and shawarma’). Some landscape-orientated poems embody a similar physicality to those laminated menus one has to turn on their sides to read. By way of this genial and inventive gastropoetic conceit, the poems invite us to break bread with them, to ruminate on issues surrounding migration, authenticity, and labour, exploring the ways in which our interactions with food become a vital expression of community and refuge during the COVID-19 pandemic.

sikfan glaschu is concerned with how ethnic cuisine might problematise our relationship to culture, heritage, and nation. Because a common complaint of immigrant food is its perceived lack of authenticity, Keung asks us to suspend our prejudice by focusing on the joyousness of the food set before us. In ‘china sea’, the kitsch plastic dragon adorning a Chinese takeaway becomes a charged symbol for movement between worlds, imbued with significance and specialty, just like the special fried rice the narrator is persuaded to order instead of the ‘hoose’ fried option. Another poem might irreverently juxtapose the ‘comic-sans-esque font of a spaghetti house in tsim sha tsui’ with a ‘disagreement over birthrights at a carluccios in stratford’ (‘di maggios’). The unsettled Chineseness of food becomes metonymic for the unsettled Chineseness of the poem’s racialised subject, one who seeks to assimilate to a city both familiar and unfamiliar. With its inflections of Gaelic, Cantonese, and Italian, sikfan glaschu has a strong sense of being both local and global; it asks how a citizen of hybrid and mixed backgrounds might navigate their way, via food, through an internationalised city built by migrants, haunted by its legacy of colonialism.

Strikingly, the collection juggles a range of poetic registers and forms. The long poem ‘notes on coffee’ lampoons hipster coffee culture as well as drawing attention to the minimum-wage service industry. By describing the banal daily aggressions the ‘master barista’ faces, Keung flips the poem into a satire of pseudo-Buddhist philosophy, its self-help verses tinged with wry Orientalist moral guidance:

you must be present at minimum five minutes

before your shift begins

failure to do so will result in penalties

such as one more year being added to your lifespan

which you will have to spend here

Yet Keung is quick to undercut this deferred enlightenment by showing us how the cycle of life turns with monotonous routine, and the service workers become cannibalised by the harsh insistence of capitalism: ‘any and all training will be done in your own time […] another minute during another shift / on another day in another week’.

From waiting staff to delivery drivers, from freelance artists unable to pay their bills to migrants at risk of eviction, sikfan glaschu is saturated by a sense of precarity. One cannot help read the collection’s second section, ‘a lockdown changes everything / nothing’, and wonder how these restaurants have fared during the pandemic. These poems about the ‘new normal’ never feel naively opportunistic (‘the wee curry shop’); by using the food industry, and its essential workers, as an anchor to think about capital, labour, and class, Keung’s poems feel timely.

Much as the ways we eat have had to change as a result of the pandemic, so the lockdown poems demand a shift in the way we read sikfan glaschu. We notice the moment where the maître d’hôtel refuses to shake the customer’s hand. We shudder at the implied them versus us in the lines ‘you cant trust what any of them say’ or ‘they should prioritise people like us before others’ overheard at a supermarket (‘conversations from the line outside the supermarket’). We become painfully attuned to the speaker’s helplessness, as their dining habits are now implicated in a cycle of harm and risk towards those people who are unable to ever work from home. Even when the poet of ‘stay inside’ is at home, the anxious task of sustaining a body and mind during this crisis is encapsulated through the starkly honest epistrophe:

the hospitals are all too full and i cant look after anyone

my friends are scattered all over the world and i cant look after anyone

the nurses are roaming empty supermarket aisles and i cant look after anyone

[…]

thousands have died in china and i cant look after anyone

zines are asking for poetry submissions and i cant look after anyone

If the act of eating with care in sikfan glaschu feels fleeting and transitory, if the same taste can never be felt twice, then the book’s depictions of mundane dining experiences –especially those set at the local KFC or Greggs – feel worthy of tender protection.

Ultimately, this collection emphasises the nostalgic quality of food, exploring how, over the last year, those moments of longing and regret, the meals-that-could-have-been, feelings that cannot be said nor translated have only accumulated; food becomes a portal allowing the narrator to speak through time and continents towards friends, family, and even former selves. Keung’s creative psychogeography, by way of the gut, conveys an embodied city of hopefulness in the face of hardship and tragedy, asking us to reorientate ourselves in this current moment of solidarity within the Asian community, so that even in the seemingly simple act of eating, our mouths are open wide as if to say:

we will not disappear into myth or art

(‘loon fung’)

we will not allow you to extinct our bodies

[…]

dont think that we cant fight back

dont take our silence as a muteness

Jay G Ying is a Chinese-Scottish poet and MFA student at Brown University. He is the author of two poetry pamphlets: Wedding Beasts (2019) and Katabasis (2020). He is a Contributing Editor for The White Review.

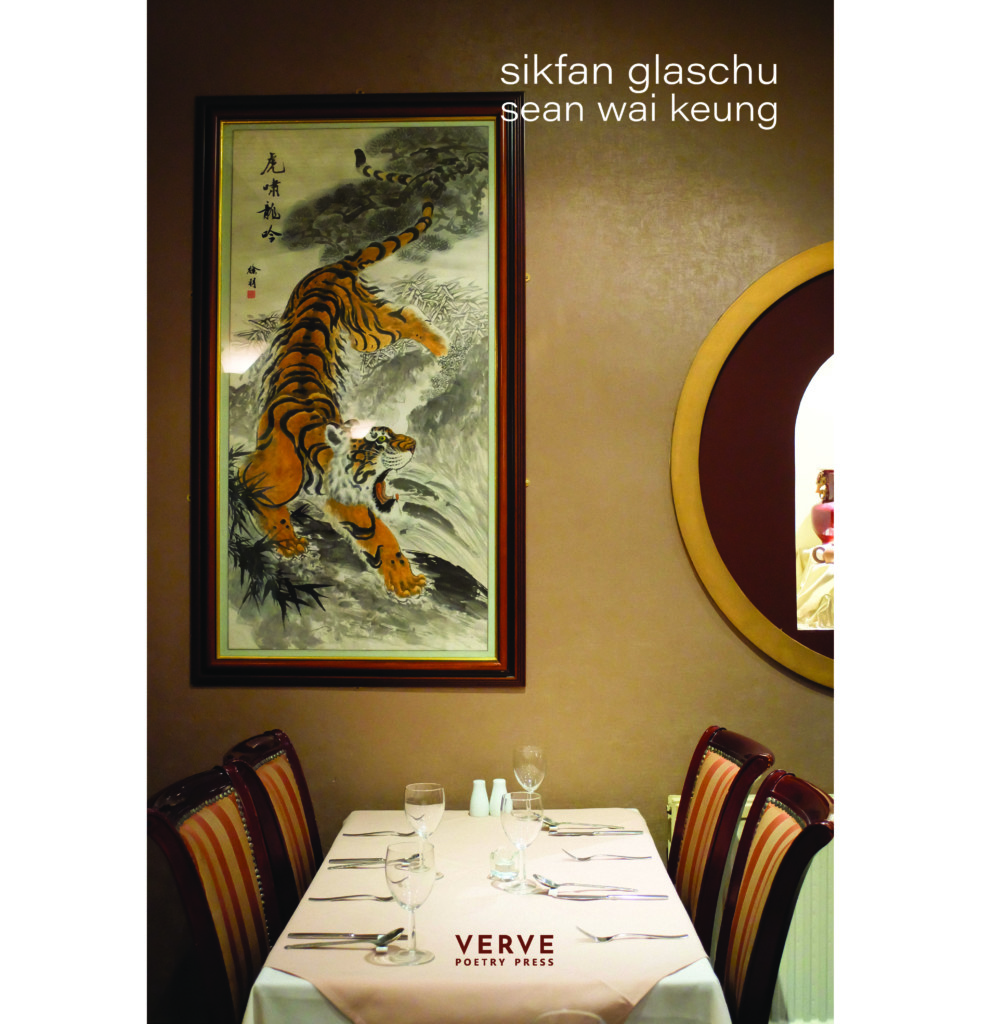

sikfan glaschu by Sean Wai Keung (Verve Poetry Press)

Jay G Ying

Jay G Ying

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.