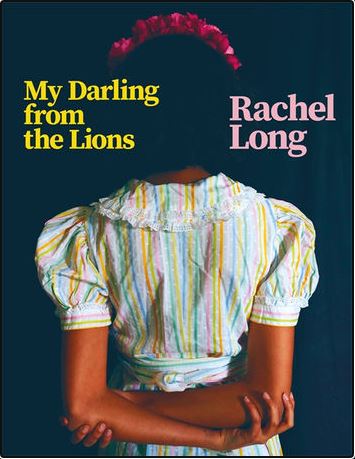

Rachel Long’s debut collection, My Darling from the Lions, interweaves accessible narrative poems with surrealist ones to explore a mixed-race speaker’s arrival into womanhood.

Five nearly identical versions of the poem ‘Open’ occur in the book’s first section. Each features an ‘I’ engaged in the same dialogue with different interlocutors:

This morning he told me

I sleep with my mouth open

and my hands in my hair.

I say, What, like screaming?

He says, No, like abandon.

The speaker’s pose signals seemingly contradictory emotions – terror and pleasure – and, asleep, she must rely on another’s reading of her body. The title ‘Open’ suggests being ‘open to interpretation’, and she hands over authority in the iterations of ‘Open’ to a lover, her mother, a friend, and by extension, the reader. Each gets to interpret her body, her feelings. As the book progresses, exploring development through sex, family, and race, the speaker often embodies contradictions, positioned in an uncomfortable in-between space as she attempts to take charge of interpreting her own experience.

Musical, celebratory poems about burgeoning sexuality like ‘Sandwiches’ (in which ‘Already, Tiff’s a reckoning: / bomb glitter on lids, oil spill on lips, sandwiches / padding her bra’) provide moments of self-aware comedy in what is otherwise a dark collage of coming-of-age moments. In ‘The Clean’, a young woman purges fatty foods so that she can feel good again:

Girl, you can be new,

surrender it all

into one bowl. This,

your hollow.

The reasons for this self-harm framed as self-love might be found in ‘Night Vigil’, which reveals childhood sexual abuse at church. A younger sister sleeps while ‘the evangelist with smiling eyes’ who ‘had blown candles for hands / […] led me down an incensed corridor, // and I followed.’ The gentle beauty of the music – the assonance of ‘own’ in ‘blown’ and the doubled ‘and’ sound in ‘candles for hands’ – feels jarring when paired with the image of fingers that are at once impotent and capable of igniting and burning. ‘Incensed’ also pulls in two directions, suggesting a corridor full of ceremonial smoke as well as anger. After the silence of the stanza break, the line ‘and I followed’ feels heavy with self-implication. The girl, who protects her sister by urging her to stay asleep, understands that there is danger in this scene, yet seems also, tragically, to accept blame for following the evangelist.

The book’s second section, ‘A Lineage of Wigs’, is reminiscent of American poet Marilyn Nelson’s how i discovered poetry in that a girl looks wryly at the adults around her, often seeing them more clearly than they see themselves. Long pays tribute to a Nigerian mother whose spirituality the daughter both admires and makes light of. The opening of ‘Mum’s Snake’ exemplifies this tension: ‘Firstly, Mum wouldn’t like that I’ve called it her snake. / It wasn’t my snake! It was the snake she put on me.’ The mother gets to override the ribbing; much of the poem is in her voice. She describes the curse laid upon her by her American sister, lifted when an ‘old prophet from Nigeria’ prescribes that she shave her head. Later, in her room – ‘half chapel, half boudoir’ – the mother will ‘lay her clean-shaven head to pray’ to Jesus ‘till her knees and elbows are sore’, unbothered by her apparently contradictory religious loyalties.

Though questions of race are explored throughout the collection, explicit racism, which erupts into violence, does not appear until the book’s third section, ‘Dolls’. ‘Interview with B. Tape II’ is a dramatic monologue in which a racist female Barbie reflects on a Black Barbie, Steve, moving to the neighbourhood: ‘Steve was so black he never bruised, I mean // crime went up in the area!’ The poem makes fun of Barbie, but humour turns to horror when Ken brutally attacks Steve.

By transitioning from poems about real dolls to poems about people treated as dolls, like Meghan Markle, the book reveals the dehumanising effects of racism and celebrity culture. In a style reminiscent of Plath’s ‘The Applicant’, the first-person-plural speakers of ‘Black Princess! Black Princess!’ size up Markle, letting her know how she falls short of their expectations. Like Plath, Long uses light rhymes and a sardonic, interrogative tone, figuratively dismembering Markle:

Do you know your blood type? When was your last period?

Smear? Chemical peel? Your doctors will be questioned,

nothing severe, just a gentle checking all is in order,

that your womb is suitably ermine-lined.

Long tends toward narrative, but some of her most surprising poems employ surrealism and non-linear syntax. ‘8’, the age at which the sexual abuse occurred, begins with a child’s-eye-view: ‘i’m pressed / apple against that wall that sunday / that school wash wash wash me’. The caesurae create breathlessness, a space for what cannot be said, and for the reader’s imagination. Interwoven italicised quotes from Psalm 51:7 request of God: ‘wash me, and I shall be whiter than snow’. The psalmist did not have twenty-first century race relations in mind, but the speaker’s request to be ‘whiter than snow’ suggests a desire to be scrubbed not just of the abuse, but of her body. The poem turns when it morphs into a scene from adulthood:

eyes wide coked up wash me I wash

me I whiter than gloss slathering

the hole that is my mouth or my

cunt

Here, the words of the Psalm shift from a request of God to one of self-determination: ‘I wash / me.’ However, while the speaker grasps some power, the scene ultimately feels more indicative of giving up on God’s assistance than it does of self-actualisation.

Long’s collection follows a speaker through a labyrinth of childhood and adolescence only for her to emerge into the labyrinth of early-adulthood. Abuse, racism, and misogyny erode her sense of self-worth; complex, imperfect role models like her mother help to restore her. Psalm 35 asks God to stop looking on and ‘rescue my soul from their destructions, my darling from the lions.’ Long’s debut gives little hope for heavenly intervention; rather, the messy muddle is left to those on earth.

Emily Pérez is the author of House of Sugar, House of Stone and co-editor of the forthcoming anthology, The Long Devotion: Poets Writing Motherhood. A CantoMundo fellow and Ledbury Emerging Critic, she lives in Denver with her family.

Buy My Darling from the Lions from Picador (Pan MacMillan)

Emily Pérez

Emily Pérez

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.