Vahni Capildeo is an astonishingly prolific and inventive poet, and Like a Tree, Walking, showcases the full range of their imagination. The collection begins with a poem ‘In Praise of Birds’, which captures the spirit of the work as a whole:

In praise of high-contrast birds, purple bougainvillea thicketing the golden oriole.

In praise of civic birds, vultures cleansing the valleys, hummingbird logos on the tails of propeller planes […]

In praise of the early bird who liberates the dewy worm from glaucous grass.

Here, Capildeo creates a world for birds that lingers somewhere between the human and the natural, reminding us of all the ways in which our environment serves us without our recognition, or even awareness. Birds not only form their own society but are part of ours, our civilisation. Yet, they also subvert the structures we have built: the ‘early bird’ liberating the worm from the grass reminds us that the non-human world has an agenda of its own.

This juxtaposition of the ecological and the political is a central facet of the collection. Capildeo’s touch is light, their meaning never forced, yet even their longer poems maintain a quick pace and a clear sense of rhythm. The collection’s appeal lies in its wide-ranging influences and its ability to approach challenging and controversial topics from an accessible, fresh angle. ‘Windrush Reflections’, for example, speaks to Capildeo’s Trinidadian heritage as well as their distance from the history that has shaped them:

They came in earlier ships,

Mahadai’s ancestors and mine,

with hope, and by imperialist design;

and I am too young to have seen them

dying, as she says, on streets.

I am resigned to dreaming them

wherever Victorian iron

palisades the public squares

like spears. I take her word

that the bread they died wanting

was British; the languages

and laws denied them were British …

Capildeo’s unconventional approach to political poetry – reflective, observant, and layered with voices other than their own – gives the collection a distinctive intellectualism and poise. These qualities are interwoven with Capildeo’s sparkling wit. In ‘Odyssey Response’, for example, Capildeo revisits Homer’s epic poem with an eye to the legacies of European colonialism. ‘Time Traveller, if you see Columbus, shoot on sight’, they urge before turning their attention to the Muse: ‘O Muse, make the poet move on. Memory is no good / to triumphant civilizations.’ The irony, as Capildeo points out, is that ‘triumphant civilizations’ of Europe did their utmost to extinguish alternative forms of memory – the Odysseys of the peoples they colonised – while holding up their own foundational epics, including that of Columbus, as inviolable.

Capildeo trains this same observant gaze on the present day. Though they avoid writing extensively about the pandemic, the series of ‘Plague Poems’ that touch on the coronavirus and its effects on human relationships showcase Capildeo’s characteristic insight and dexterity:

You may kiss me as much as you

like. I wish you would. I always

wish you would. I wish you always

would. You’re the only one allowed

to kiss me. The science is, lack

of touch can make you ill, even

physically. Sometimes when you

breathe, I start breathing just like you.

Desire, isolation, and desire in isolation – each has its place in these lines. Double-entendres and ironies abound: Why is the addressee the only one allowed to kiss the narrator? Is this a declaration of love or a sigh of frustration at the separation brought on by lockdown? If contact can make you ill, then shouldn’t lack of touch keep you safe? Following Capildeo’s thoughts in this way reveals a mind that is deeply reflective yet constantly alive.

The same linguistic twist offered in the first half of the above extract reappears later in the collection in a prose poem ‘In Praise of Trees’: ‘Listening to a tree with another person, listening with a tree to another person; listening or hearing? Who conducts attention to the rim of the sky? Start there. Start twice, and that is twice again.’ Here, Capildeo demonstrates that their purpose is not so much to admire the complexities of the natural world itself as to explore how nature infuses itself into human relationships. ‘If There Is an Afterwards’ develops this sense of purpose further through a meditation on connection and loss:

I’ll find you. Where we met. On stone-bright streets

I imagine. We may have lost people,

not ourselves; not yet ourselves. If we have

much to say, we do not say it: we have

had years. A new friend is with us. New friends

are hard to make, in middle age. Who can

introduce us? Silence runs like treacle

over flint; coffee; river water; new

words, like petrichor; green willows, no words.

Several erasures and ‘expanded translations’, where Capildeo has taken the works of other poets and added their own variations and additions, make Like a Tree, Walking experimental in the typical sense, but it is in poems like ‘If There Is an Afterwards’ where the collection’s ingenuity becomes most clear. Capildeo’s strength lies in their use of the natural world as a mirror – or an extension – of human experiences. In the presence of mortality, water and wilderness step in to fill the silence, and coffee and other hallmarks of humanity become enmeshed with the non-human world.

Much of the collection is imbued with this spirit of natural connection and wonder, and Capildeo’s ability to read nature, and to identify its presence in the midst of human society, makes their latest collection a thought-provoking read.

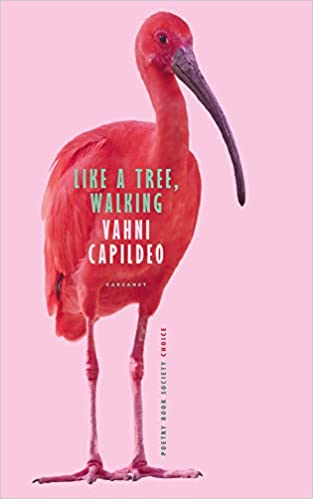

Like a Tree, Walking by Vahni Capildeo. You can buy the book here.

Maggie Wang studies at the University of Oxford. Her writing has appeared in Poetry Wales, Versopolis Review, and elsewhere. She is a 2021 Ledbury Emerging Poetry Critic.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.