Our New Damage

What are the contours of heritage when it ruptures through colonialism and diaspora? This dense, multifaceted question is the organising principle of Anthony Anaxagorou’s new collection of poetry, Heritage Aesthetics – primarily concerned with the underexamined intersections of British-Cypriot identity, colonial history, and masculinity. Geography and cartography yield structural anxieties: littoral Cypriot scenes appear in sharp contradistinction to Britain’s bleak violence, with the speaker ‘still looking for a place to park / my mixed up blood’ (‘My Weapons Are Working People’).

Structured via the division of Cyprus, the book contains two ‘Territor[ies]’ with six subsections. Ever the linguaphile, Anaxagorou places language under immense pressure, sensitive to both the common nature and corruption of speech, desiring to ‘repurpose each syllable with a fairer / way of shaping’ (‘Now My Ego Wants Better Things’). One can locate cartographic anxieties in the caesura breaking up island: ‘I’m writing this is- / land guilt’ (‘Versive Diagnosis’). Furthermore, colonialism and masculinity are hauntingly indivisible, as Britain’s ‘yesterday is father-terrifying’ (‘We Are Us Now’). Present throughout the collection and introduced in the opening poem, is an overwhelming sense that history is being remade to the point of erosion or exhaustion, ‘tonight / we’ll sleep inside our new damage’.

In ‘Territory One’ the poet is a weathervane to political turmoil. Anaxagorou harnesses the ‘lexicon of power’ prevalent in British current affairs, restructuring the mechanics of language in a poetics of immanent critique. ‘I read another white tell- / ing us to go back to where we once were alive’, he writes in ‘My Weapons Are Working People’, expropriating the xenophobic phraseology of immigration politics and repurposing that epithet with a subjective, exilic response. Highlighting the absence of racial parity – as evidenced so overtly by the murder of George Floyd – Anaxagorou invokes the significance of Floyd’s final words ‘I can’t breathe’ as used by the BLM movement, and the importance of breath in poetic construction:

… isn’t the future made up this

way – of people like us becoming the history

of the way we tried to breathe

‘Futurist Primer’, employs the collision and virility of the Italian art movement which influenced fascism:

… in a few hours a man will

walk down a street in Birmingham to drive a knife

into a person he’s never heard laugh

The phallic imagery of stabbing is echoed in the final lines, ‘before I do anything else / I’ll think the penis really does not age well’, refusing the hyper-masculinity of Italian Futurism. Coolly switching between brutal reportage and a pompous mode of address – ‘I’m sipping Americanos with six new interns / pontificating on the stoicism of lifeguards’ – peppered with middle-class details like ‘organic kale & deals / on kombucha’, the poem’s speaker distils into lyric the desensitisation to everyday violence.

Concerned about tradition and legacy, there are maxims for the speaker’s progeny, ‘violence / only teaches us how to keep returning to it’. Family structures within capitalism are further examined in the poem:

my landlord spends his holidays on a Cumbrian field

with his wife who coincidentally happens to be my brother’s

landlord …

(‘Futurist Primer’)

Private ownership and class systems in Britain allow certain families to dominate and oppress others, echoing the country’s reluctance to abandon feudalist values and relating to the book’s territorial structure. Heritage, from the Old French iritage meaning ‘heir, inheritance, ancestral estate, heirloom’, relates to material property.

The title poem forms a lyric essay scrutinising British nationalism, held within a reading of The Ending of Time by J. Krishnamurti and Dr David Bohm. A boy ‘who was made to learn / the national anthem before his birth-skin’ appears next to a man in an England shirt, ‘grabbing him in the way men do / when they know they’re winning’. The man subsumes the boy in ‘a violence so exact it sanitises history’. An incident titled ‘Tottenham 2003’ is depicted, carried out by three officers with ‘cuffs poking out readymade moons’, who ‘yanked’ out ‘our boy’ from the car:

like a dummy from a charity box a party

cracker for a housewarming friends forgot

about they beat him wide open like a dog’s jaw

Shifting between similes, Anaxagorou represents the severity of state violence, his speaker bearing witness to racism in the police force. Rendering the action in superscript indicates the inexpressibility of such cruelty, the typographic device notates trauma and suppression in which figurative comparisons supersede the event. Protean in form, the poem approaches its subject from multiple perspectives. ‘Heritage Aesthetics’ and ‘Quotidian Theory’ constitute two long poems engaged in conversation with theorists, whose work is approached when ‘certain / literatures require you to explicate / your life experience’.

‘Territory Two’ opens with the formally arresting poem, ‘Though I am glad to be among the bitumen in a city’, which uses text from photographer Basil Stewart when he visited Cyprus between 1905 and 1906. Each couplet begins with an italicised line from Stewart’s travelogue. From there, the speaker’s voice recontextualises the original, writing back against colonial discourse.

Anaxagorou’s political lyricism possesses an isolated voice dismayed with the commodification of contemporary existence, yet concealing a tenderness informed by his son, representing a future in which it’s no longer ‘fine for boys to feel terrible & ruined alone’ (‘Across from Here’). Heritage Aesthetics is an intervention in (re)writing the past to claim identity and heritage, which evokes Eavan Boland’s theory of the rift ‘between the past and history’:

it was plain to me that the past was a place of whispers and shadows and vanishings, and that history was a story of heroes […] I was interested into what disappears into that past.

In an optical concertina, Anaxagorou closes the book with these remarkable lines:

a family settle around a

continent next door the odour

is like a grave hurled through

the window becoming a throat

living inside the noise

it attempted to make

Solitary on the page, this sestet bears the fingerprints of Anaxagorou’s poetic operation, linguistic precision, syntactical play, and impossible images upending readerly expectation. Death – in both malodorous decay and the idea of cessation or oblivion – lurks beneath the surface of this collection. The ‘grave hurled through / the window’ articulates through imagery the conditions of postcoloniality, limited access to healthcare and poor living standards for racialised bodies in the state. Windows symbolise possibility tethered to the grave, transforming into a voice attempting to escape.

Crucially, Heritage Aesthetics supplies contemporary audiences with an excavation of Cypriot history that attests to legacies of colonialism and violence present in Britain and other post-imperial nations. Though oriented to language’s potential, no word is dispensable in this bravura display of poetic dexterity.

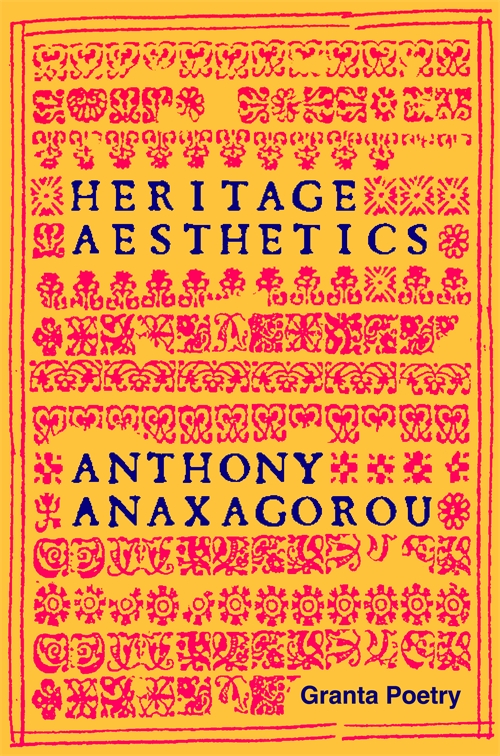

Heritage Aesthetics by Anthony Anaxagorou

Granta Books, 2022

You can order the book here

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.