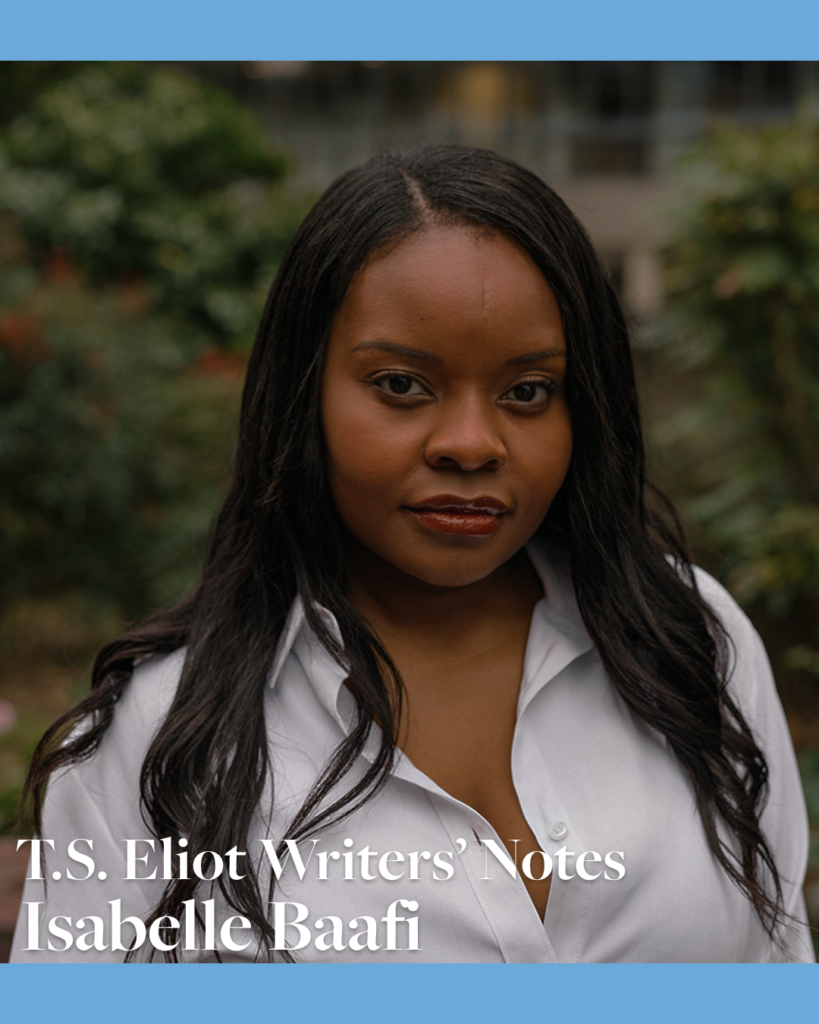

Welcome to our Writers’ Notes for the 2025 T.S. Eliot Prize shortlist. These are educational resources for poets looking to develop their practice and learn from some of contemporary poetry’s most exciting and accomplished voices. Here’s Isabelle Baafi on her collection Chaotic Good.

Pearls of Wisdom

A poetry collection is the result of more than one person’s efforts and insight, even though most collections only ever have one name on the cover. In addition to the experiences, artworks, words, encounters, insights and memories that inspire you to write in the first place, the writing process usually involves sharing your work with others: testing your ideas, exchanging opinions, gaining a fresh perspective. Also, being humble enough to consider your peers/mentors/editors’ feedback and – where appropriate – determined enough to apply those changes, or at least attempt to. With poetry, as with so much else in life, you get out what you put in, and being open and adaptable will be one of your greatest assets.

With that in mind, I’ve decided to share some of the most valuable pieces of feedback I’ve received or heard over the years, as well as a few tips that I often find myself giving as an editor, mentor and facilitator. Of course, poetry is not a one-size-fits-all craft: what is necessary for one poem may not be necessary for another. But what these bits of feedback have done, for me, is challenge my perception of what was possible and open new doors of possibility for where I could take my work. I hope they do the same for you.

‘There are a lot of round things in this poem’

I can’t remember what the poem was that generated this feedback, but I found it super interesting when a friend of mine said this during a writing group session. In that moment, I cast my eyes back over the poem and noticed that there were indeed a lot of round things: a bowl, a spoon, an eye. The feedback was more of an observation than a constructive criticism, but what I think it highlights is that every poem has its own internal architecture. There are ideas, images and sounds that will arise – often through conscious effort and diligence but sometimes unconsciously. As you edit, you may be delighted to look back and realize that, ‘Yes, this image has some associative relationship with this one. This detail I gravitated towards naturally is actually the fulcrum, the point around which everything else is levered.’

It’s something to think about: why are you mentioning the objects you are? What associations do they evoke? Do those fit in with the rest of the poem? Is there anything that could work better or have a more interesting effect?

For instance, in a poem I took to a different group, I once mentioned brioche as a symbol of things falling apart. After all, brioche is quite crumbly. But a fellow poet suggested that the brioche was too gentle an image, too soft, and in the end, I decided that for the acerbic feeling I was trying to evoke, it actually was. But rather than choose something hard I replaced the brioche with a pinwheel – a domestic object, a toy – that is moved by an unseen force, sometimes uncontrollably, sometimes very quickly. So quickly in fact that everything becomes a blur. Thinking about the poem’s internal architecture helped me to deepen my engagement with its emotional register.

‘This line is not as strong as the others’

A good friend of mine used to say this from time to time and I always knew exactly what she meant: ‘Isabelle, this is not a good line.’ But I appreciated how gently she was saying it. And the wording actually raises an important point, in my opinion: that a poem is only as good as its weakest line. And so when you’re editing, it’s important to go through with a fine-toothed comb and refine the most lacklustre, imprecise or inessential lines until all of them feel strong, or at least until each one is doing something vital and interesting. Maybe, once you’re in the final stages of editing a poem, you can set yourself the challenge of picking out the weakest three lines each time and changing them until they’re among the strongest – and then doing that over and over until all the lines have been changed (creating a ‘Theseus’s poem’ if you will!) or at least all the lines are really strong.

It’s up to each poet how far they push their lyrical adventurousness, how wild their imagination, how unruly their syntax, how unusual their imagery. But making the effort to create something people won’t expect (somehow) is one way poets do the mighty work of altering how readers see the world, and how they themselves see it too.

‘What would happen if we turned this upside down?’

I learned this brilliant tip during my creative writing postgraduate course. Now of course, this won’t necessarily work all the time, but sometimes people spend the entire poem building up to the most interesting image or idea. However, it’s important to grab the reader’s attention as soon as possible, and so sometimes that dynamic, layered, complex, evocative last line should actually be the first, and then everything that previously came before could be the deconstruction, the unpacking. Or you could write past that ‘ending’ into a new, more exciting journey. That’s how one of my favourite poems from my collection, ‘Chiaroscuro’, began. The original first draft ended with the image of a brother piling sand on the speaker until she couldn’t breathe. And I thought to myself, what if that’s not where ‘it’ ended … but actually where it all began?

‘Write about it without naming it’

The fun thing about riddles is that they deepen our understanding of the things we typically think of as pedestrian and replaceable. If I point to an object and say, ‘This is a chair’, nothing happens. But if I tell you, ‘This is a creature with four legs that holds you up when you can no longer stand’, what happens? You start thinking about the entire existence of the chair: how it came to be, what it’s made of, how it reached you, how strong it is. You think about the things you go through on a day-to-day basis and your aching limbs, your sore back, your spent body, your tired mind. You feel gratitude towards the chair; you feel indebted. You understand that your existence and the chair’s existence are intertwined. The same thing happens when you write about an object, idea, person or place without naming the thing itself: you peel back the layers and are better equipped to address the types of broader, ontological questions that energise so much of modern lyric poetry.

‘There are a lot of ideas in this … perhaps too many ideas’

This feedback probably saved my collection from being quite messy, to be honest! When a poem has too many ideas it often leads to a piece that feels jumbled and unfocused – almost like the images and expressions are contradicting each other and pulling the reader’s mind in different directions. Now, of course it’s good for a poem to be broad in its thinking: to capture layers of truth and shades of meaning. And believe you me, I understand about contradicting thoughts! What I’m talking about is conceptual coherence. If I ask you two questions at once, you can’t consider either of them, let alone even think about answering them. Technically, your poem can be about more than one thing, but I think it’s best for a poem to have a main theme, like the spine of a skeleton, and then for any secondary images, ideas, complications or wider context to branch off like ribs.

A good way to think of it is: can you sum up your poem’s theme in a question? I say a question rather than a statement because I don’t think a poem should be closed or definitive; it should open up; it should encourage, invite and perform some form of discovery, exploration or uncertainty.

Isabelle Baafi is the author of Chaotic Good (Faber & Faber / Wesleyan University Press, 2025), which is a Poetry Book Society (PBS) Recommendation, and Ripe (ignitionpress, 2020), which won a Somerset Maugham Award and was a PBS Pamphlet Choice. She won First Prize in the Winchester Poetry Prize 2023 and Second Prize in the London Magazine Poetry Prize 2022. Her writing has been published in Granta, the TLS, The Poetry Review, Callaloo, The London Magazine, and elsewhere. She is a Ledbury Poetry Critic and an Obsidian Foundation Fellow. She edits at Poetry London and Magma.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.