Scottish literature of the 20th century particularly is well-known for its humanism and pluralism.

You just need to think of the likes of folklorist and poet Hamish Henderson, himself a bisexual man, arguing that poetry and song could help heal divided communities and societies. His most famous song ‘The Freedom Come All Ye’ is an open invitation for all to take part in a new progressive society. However, it is also known that Henderson’s sexuality was the target of other, less tolerant contemporaries, such as Norman MacCaig, who sought to retain a strongly man-based, homo-social culture where heterosexual male poets had an ‘alpha’ status.

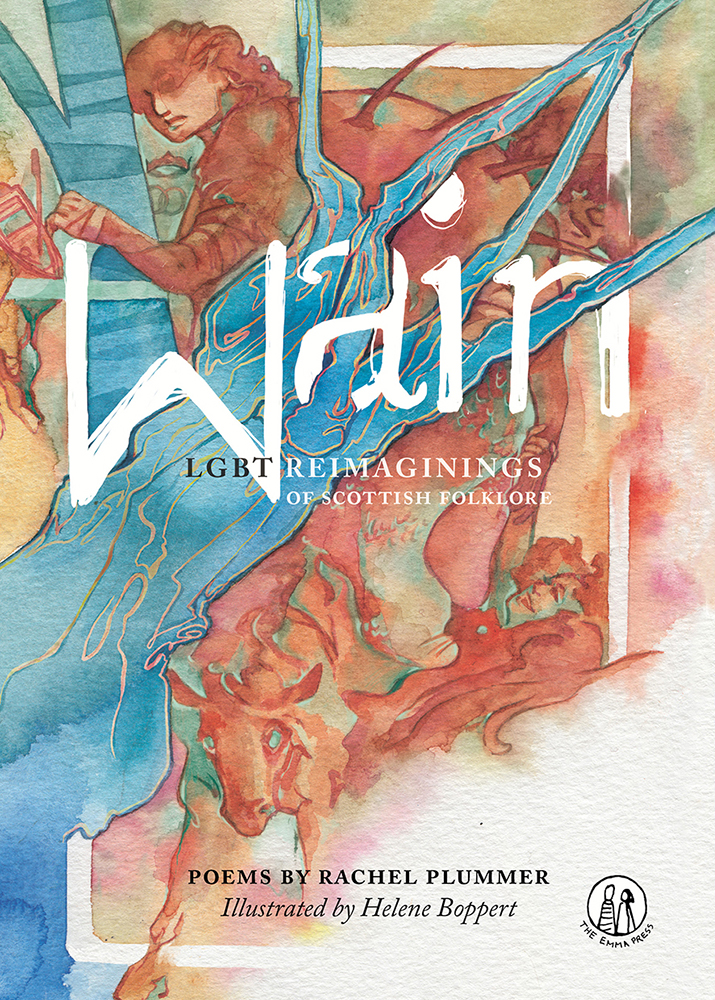

Scottish literature of the 20th century does not have a good track record as regards women writers and writers of colour or differing sexuality, although all of these voices existed almost in legion. What Rachel Plummer has done here, with the assistance of beautifully fluid watercolour illustrations by Helene Boppert, is to re-invent Scottish folktales and lore in a way that helps to redress the skewed balance. This book as such is an extremely welcome and needful addition to the overall story of how nations reflect themselves and their values through narrative and song.

Scottish writing and literature is deeply imbued with fairy stories and myth, but they are invariably those of an overtly or covertly heteronormative kind. Take one of the most famous, ‘Thomas the Rhymer’, the story of a travelling musician / poet who takes a rest underneath the Eildon Tree and is suddenly seduced and led astray for years by a Fairy Queen. The female figure is otherworldly and possibly malign and the male figure is the hero under threat.

Time and time again we encounter enchanting and eldritch tales, but they all seem to reinforce a traditional performance of gender and sexuality. But written within the very genetic makeup of these stories is the potential for destabilising or Queering them. They are, after all, about relations between two worlds, and breaking down the barriers between them to encourage a fluidity and hybridity of contact between the human realm and the ‘Secret Commonwealth’ of fairy people. It’s here that Plummer breathes new life into old tropes and tales. If a ‘Selkie’ is a creature that shapeshifts between a seal and human form, who’s to say that gender is not like a sealskin that we can wear or take off?

The secret me is a boy.

He takes girlness off like a sealskin:

something that never sat right on his shoulders.

The secret me is broad-shouldered;

the sea can’t contain him,

the land can’t anchor his waves

to its sand.

This collection also contains an interview with both the poet and artist and Plummer’s last piece of advice to any reader of the book is ‘Don’t be afraid full stop’. It’s worth pointing out here that the target audience of this book is teenagers, though the very title Wain suggests that it’s also fit for bairns, weans, little ones.

In fact, I’d go as far as saying that perhaps by the time an adolescent gets their hands on a copy of Wain it might already be too late. We tend to ruthlessly condition our children in terms of gender and sexuality in an inflexible way from a very early age that is far from healthy. Plummer’s message of supportive positivity and self-affirmation through legend and myth reassures any young reader that there are so many shades of being — that it is important, though often hard, to be who you are or want to be, not what others demand or expect to you be.

I should also stress that what Plummer has done here is not simply take an old yarn and ‘Queer’ it in any merely gestural way; it is a far more profound process than that. The great triumph of the book is its attempts to rewrite similes and collocations; that is to say the company that words and concepts keep. One of my favourite examples is how the Selkie ‘swaggers like a mermaid’. It demands the question, how did we ever reach the point where we thought a mermaid could not swagger?

A number of the poems work in an allegorical way in that they could be taken at face value but also have deeper resonances and seem to speak for conditions in our own human societies. ‘Blue Men of the Minch’ is a poem dialogue between the leader of the Blue Men (storm kelpies) and a boat captain who happens to be sailing over a particularly choppy stretch of the Minch. Traditionally if the Blue Man uttered a couplet of verse and the captain could reply with their own rhyming couplet, the ship was spared. However, the poem could also be taken to be symbolic of the difficulty of a same sex relationship in a certain place at a certain time and the real tragedy comes not from the fear of the ship being scuttled but the denial of true feelings for fear of repercussions:

Sea Captain, Sea Captain, could you not love

me and live with me here in the blue?

Storm kelpie, storm kelpie, well could I love,

but I cannot remain here with you.

Sea Captain, Sea Captain, then I must raise up

a strong wind to set you free.

Know you will find me out here on the Minch

if you ever return to the sea.

Plummer’s poetic reinventions of these mythical figures and their stories are never didactic, other than offering the reader the latitude to be themselves or see their own lives made mythical through the prism of these stories. There are too many characters and creatures to mention, but another favourite poem of mine concerns the ‘Nimblemen’, who are said to be giant warriors who fight and dance in the sky and by doing so create the Northern Lights. The poem is in their collective voice:

For us, the night sky

is a dancefloor. Look at us ceilidh

under the disco ball moon.

Fabulous warriors. Merry

dancers. Bonny lads in green

lipstick, flicking

our well-glittered hair.

Other poems, such as ‘Nessie’, are important for reminding us that we also have to learn to move beyond our desire as humans to name, label and thus safely compartmentalise every person and thing we encounter on our journey through life. The hunt for ‘Nessie’ as such seems to become something akin to victimisation:

The Loch Ness Monster isn’t a boy

or a girl.

Nessie doesn’t have much use for words like that.

(…)

Nessie knows who Nessie is

and isn’t.

(…)

Not a boy or a girl. But real.

These stories and poems may seem at first glance to come from a fantastical and imaginary place, but their roots are in the real, physical world where people each day struggle to come to terms with what they are, and are persecuted for simply trying to be themselves.

Plummer knows that this has to stop, but she also understands that we cannot simply jettison hundreds of years of story-telling in the name of progress. These poems are a deeply humane and necessary way of rehabilitating the old with the new and I wish as a child I’d had access to such resources as the poems and paintings in Wain.

You can buy Wain from The Emma Press.

If you’d like to review for the Poetry School, or submit a publication for review, please contact Will Barrett on [email protected] or Ali Lewis on [email protected]

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.