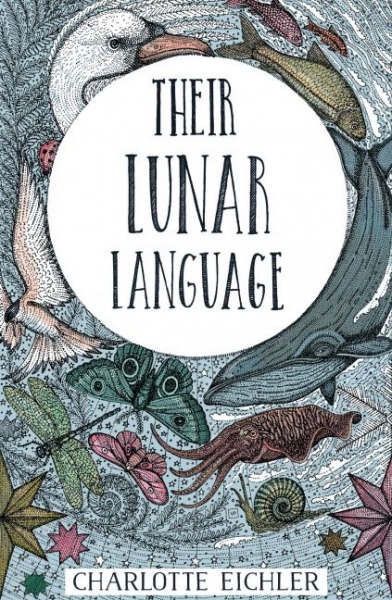

Charlotte Eichler’s debut pamphlet Their Lunar Language opens on a wryly prophetic note: ‘We knew everything, playing oracle on the carpet. / Saturdays crawled with our ladybird circus – ’ – lines which capture something of humanity’s uneasy assumptions of power over the natural world.

Vahni Capildeo has described Eichler’s poems as ‘modern pastoral’ and this pertinent collection explores the dynamic, often ambivalent places where human and non-human intersect. As the poet Karen McCarthy Woolf recently wrote, citing Juliana Spahr, we need to write not only of the beautiful bird in the forest, but the bulldozer ‘off to the side that is destroying the bird’s habitat’ – a mode of contemporary writing that Eichler skillfully employs.

Their Lunar Language subverts the pastoral by teasing open idealistic assumptions of the rural as a setting of innocence. In Eichler’s hands, the natural world is shifting, slippery territory, inclusive of human culture, where ‘Our children dance in dirty sandals / on the slick black head of a whale’ (Kaktovik).

A striking poem – ‘The Fifty-Year Traffic Jam’ dissolves boundaries between the natural and man-made to create surprising, fresh work that toys with our preconceptions of ‘natural’ beauty. An abandoned car is surrounded by ‘rusting fern’ and dragonflies are ‘electric’ with ‘copper wire wings’. A forest moves away from being a passive object of pastoral musing and to an active entity which absorbs the vehicles and their leaking juices:

The forest drinks them in,

sucks up radiator fluid

and cogs –

.

its creaking branches

sound more metallic

by the day.

Eichler’s pamphlet has wide geographical range, taking the reader from the south coast of England to Kaktovik – an Alaskan settlement of just over 200 people which holds the dubious distinction of becoming the United States’ ‘polar bear capital’ due to climate change. In ‘Kaktovik’ she describes in spare, and sad detail how artificial boundaries between natural and man-made are crossed by starving bears:

[…] the snow sprouts claws,

pads through the streets after dark,

cracks its teeth on the bones we left behind.

.

By the icehouse, a mother

licks new colours from her fur,

.

far from her blue world

.

and the cub that melted as they swam.

.

Our homes are barred with shovels, antlered –

she’s close enough to taste the glass.

The uneasy interface between human and non-human is again invoked in ‘Fata Morgana’ as Eichler twists perspective to produce a disconcerting clarity. Surrealism is at work as ‘cod leap up to line roofs’ and kittiwakes ‘nest on windowsills / painted red to match their tongues’. Emphasising the distance between humanity and the natural world, the poem declares that ‘everything is made of unreachable light.’

There is something of the dark oracular in Their Lunar Language with the idea of divination revealing as much about the teller as the seeker herself. The opening poem, ‘Divination’, begins in the vein of a pleasant childhood pursuit recollected but takes off at a darker, more tangential place:

Saturdays crawled with our ladybird circus –

from the ends of our fingers, solemn as blood.

.

[…] Now like hanged men, we want to buy futures

And there’s someone doing tarot at the end of Brighton Pier.

A sense of the dispossessed also runs through the pamphlet. In the intimate ‘Trapping Moths With My Father,’ the moths ‘speak a lunar language / and are trying to get back’. The reader might ask who is trying to get back – the moths or the daughter trying to reach her own father through the beautiful and strange names of the creatures she so desires.

By emphasising the intrinsic value of all living things: ‘whales, gliding / despite the weight of all they know’ or moths whose ‘wings are inscribed / with eyes and feathers, / hieroglyphs you understand but can’t explain.’ Eichler manages to capture gracefully both the distance and intimacy we share with other animals.

Drawing on ideas of interconnectedness between species, she captures the complications of being human using interesting allegories from the natural world. ‘Clean White Bones’ explores the complexities of love through the medium of the cuttlefish with aplomb:

[…] I wonder

if it’s any easier for them,

with twenty legs to tangle,

six hearts to please.

.

They speak a patterned language

of moody stripes and flashes …

.

If we could take their place

there’d be no mess,

just our children in the weeds

brightening like bulbs.

Again working to dissolve the conceptual boundaries between human and beast, the beautiful closing poem ‘Valkyrie’ describes a woman watching swans from a window:

Tonight, she goes to them –

.

they croak to each other, their bright beaks,

the bow curves of their necks.

.

She looks back to her house

and her arms feather in the cold.

Their Lunar Language is a timely and discomfiting exploration of our ambivalent interactions with the non-human – and with each other. Eichler exposes our uneasy relationship with the natural world with subtlety and originality – with ‘all the sea’s dark spread ahead of us’. Eichler’s is a voice that deserves to be heard in this increasingly fractured world, in which so much is at stake. I hope she ventures closer to Spahr’s bulldozer to help us understand what we are in danger of losing forever, and, as Kathleen Jamie writes, to ‘advocate for the voiceless non-human, whose fates we both hold and share.’

You can find out more about Their Lunar Language from Valley Press.

You can find out more about Their Lunar Language from Valley Press.

If you’d like to review for us or submit your publication for review, please contact Ali Lewis on [email protected] or Will Barrett on [email protected]

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.