In Stephen Pinker’s book, The Blank State, he took aim at the notion of nurture being all powerful; that we are born in compliance with the environment we inhabit. Pinker argued that the new cognitive sciences showed we are determined by what we inherit.

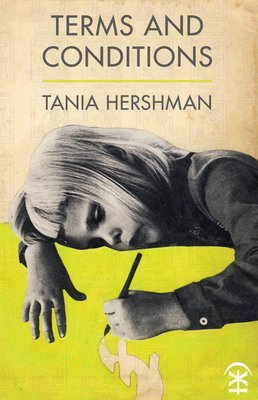

In Tania Hershman’s debut collection: Terms and Conditions (Nine Arches), the opening poem ‘Baby’ shows this thinking, of being born ‘ready’:

Baby travels

trains, collecting

faces. (Baby may seem

carried, but is, in fact,

directing.) Baby takes in

all ages, colours

male, female

other. Baby understands

the need for data.

Whether I have read this right or not, it isn’t surprising given Hershman’s background as a scientist, such ideas as Pinker’s enter the mind of the reader. Elsewhere in the collection, the science is more evident but nicely curved towards other, less predictable connections such as love. In the poem ‘Relativity’ for example, Einstein’s physics is beautifully brought into question in how not to end a relationship:

You think if you’re high enough

you’re safe You think

when I fall your orbit

is unaltered You think

this poem

is just physics

Not being a scientist myself, I learned a lot without feeling I was being taught (do you know what proprioception means? I didn’t). The poem, ‘In Tune’ uses the metaphor of a novice bell ringer learning their trade, to show how our bodies are often not in tune with themselves; if we injure ourselves for example, in this case a sprained ankle, our body has to relearn how to co-ordinate as a whole.

Proprioception:

our sense of ourselves

in space, why we can touch

our nose, eyes closed, how we

walk without thinking and – mostly

– do not fall.

But Hershman has another arrow in her quiver of talents, in bringing fiction into the orbit of poetry (a welcome addition in my opinion). Her previous books have been short stories and flash fiction, and she is holder of the wonderful ShortStops website of short fiction resources. I wondered if her writing of fiction was an antidote to the truth of science, where she could break free. But of course, the divide between fact and fiction is not so binary, and poetry is well practiced in the combination of the two. The Primers’ poet, Katie Griffiths introduced me to the idea of reading poetry in terms of its subjectivity and objectivity, where parts of the poem may be statements of facts, whereas others will have metaphor and simile. The poem, ‘For which we have no names’, seems to perfectly encapsulate this mix of science, fiction, subjectivity and objectivity.

She works one day a week

in a building which also houses

a Centre for Synaptic Plasticity,

and each time she sees the sign

she wants to go in and say,

Take my brain, bend it,

it’s not behaving.

And our poet goes on to question the limits of science when arguing against the belief that, ‘we can’t feel emotions we have no names for’, in the sense that such abstract concepts as love, loss, jealousy and anger cannot be measured:

How do we know

what anyone means when they say anger,

when they say jealousy, when they say love?

Hence why poets of any worth steer clear of such nouns. Not the subjects of course, they are the bread and butter of poetry, if not the dollop of jam as well and Hershman lets us eat plenty, often in surreal situations as in poems like ‘Life Just Swallows You Up’:

Father dies during the appetizers. Mother

keeps on eating. How’s work? she says. I

pour more wine. She passes

just before dessert arrives. Shame,

says the waiter

Love is also dealt with in an almost mundane way. In the poem ‘Body’, for example she describes being with her mother who is at the hospital for tests.

I’d helped my mother

get undressed, seen

for the first time

the vest she wore

to cover where her breasts had been.

I had not expected

several minutes later

to see her chest –

like wings unfurling

open itself out to me.

These major themes of uncertainty and control about our futures are the veins that run through the book; what we have to deal with, and how we go about it. The ‘woman in the bath’, one of; the shortest poems in a book, packs so much into a scene of doing just that, having a bath the control of the hot and cold water she gives in to, but then in the middle of the poem, when she is floating the impact of three words, ‘Yes, the womb’. Is it about childbirth, or the flushes of a menopause? Either way, the extent to which we have control, or not over our bodies is beautifully captured in forty-one words.

Similarly, the poem ‘What we don’t know, we don’t know’, which has echoes of Donald Rumsfeld, and Nick Lantz’ collection of the almost same title (bar the placing of ‘What’), reflects the uncertainty of all meaning. The form is very clever; three poems in one which neatly compounds the uncertainty of its content and how we should read (into) something.

This

uncertainty who knows anything for sure is our new

reference frame. Do purchase for a large amount and read

the handbook if you will, life moves too fast

for handbooks

Which then begs the question of what is normal anymore, to which Hershman answers in the poem, ‘Missing You’, where she has a dig at scientists in terms of boundaries of recovery and how much of us is really needed to live a fulfilling life.

without the chunk

that in us normals holds half

of all our neurons. Her brain,

the jaw-dropped doctors think,

became expert in alternatives,

workarounds, diversions. Who’s to say

she’s not finer than the rest

of us?

Based on a true story of a woman who had half her brain removed when a child, to stop persistent seizures, in the poem she is now in her twenties, married with two children. She can still breathe and seems to be doing quite fine thank you very much.

This amalgamation of uncertainty, control, fiction and fact, is enforced by the ironic title of the book, Terms and Conditions, and its three sections: data control, warranties & disclaimers, privacy policy. All of these mechanisms to control a society seem very outdated; porous barriers to a world that is moving so quickly in so many directions, in which many of us are overwhelmed with information, and where the holders of power are quaking in their nuclear-foolproof boots.

There is nothing fake news in the message of this collection. Tania Hershman has written a tightly conceived, perfectly formed set of poignant poems that question modern day (virtual) reality. It is scary, which makes it all the more urgent, for as one of the book’s characters says, ‘Who am I? Tell me my name’. We need to find out who we are, and soon.

but remember:

the instructions that you crave

are liable to dance always and forever change.

Maybe Stephen Pinker has the answer, but he should at least read Terms and Conditions. Or maybe we should ask ‘Baby’ to evaluate the world they are now entering. Yes, let’s do that.

PS: The book has endnotes, yes, endnotes, in a poetry book – read on!

Reviews are an initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at – [email protected].

You can

You can

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.