The relation between what we see and what we know is never settled.

Each evening we see the sun set. We know that the earth is turning away from it.

Yet the knowledge, the explanation, never quite fits the sight.

John Berger, Ways of Seeing

The Book of Numbers is like an artist’s sketch book, a poet showing his workings, with the process of arriving at each line every bit as important as the result.

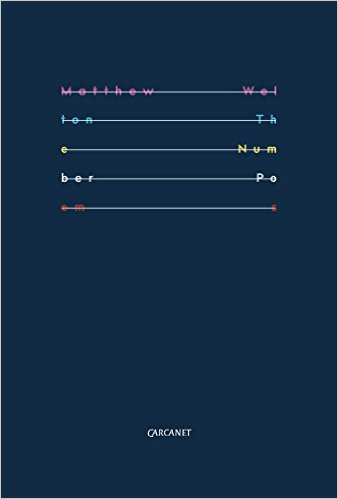

The cover of Matthew Welton’s third collection neatly introduces the content; a visual pun on a musical stave on which the poet’s name and book title are arranged:

There are five lines and five words. The neatness of this grid pattern, however, is carefully disrupted: rather than do the obvious thing – fit five words onto each of the five lines – the words are pulled apart to the extremes of the line ends, sometimes broken mid-word and running off to the next line, resembling slider answers in a multiple choice questionnaire or, as the title page reminds us, an abacus. Instead of word units, each line coheres with a pastel colour. The first impression is of deliberate modulation, softened with subtle colours, the words divided phonetically for the reader to re-make and re-combine; a visual declaration that patterning, separating and rearranging words is a core concern of the book.

Of course, it’s in the title too. All of Welton’s books include numbering, repetition and patterning as a mode of enquiry into language. How can words be arranged and rearranged to make subtle, incremental, and irreversible differences? Welton is interested in the process of laying out words like dominoes to see what patterns are created, and how far these can be extended before they fall. But it’s not simply an intellectual pursuit; it’s also a sensual one, highlighted by the visual playfulness of the cover.

The book is in two parts, ‘The book of numbers’ and ‘Melodies for the meanwhile’. Maths and music are known bedfellows and Welton applies both exuberantly. Numeric constraints abound, feet are made to be counted, and there are clear beats, syllabics and numeric sets. Aural playfulness and rhythmic friskiness generate interesting, and interestingly sustained, combinations. Several of the pieces made me laugh out loud (‘the mind’s a kind of monkey with its teeth all gone’) and delight with their wit (the poem ‘Under Jack Wood’ even seems to riff on the press quote from Jack Underwood on the book cover).

Many poems here look like ordinary lyric poems but then deliver content like this:

of how we square what we believe with how we live,

or how it is the static unemphatic fit

of word and sound and sound and thought and thought and word

.

says more about the language than the language could.

.

~ ‘Construction with phrases’

Metaphysical intensity is a cornerstone of the work. Welton doubts everything, and relentlessly employs us to doubt it too:

the gesture which adjusts each thing to the things around it creates a reality so plausible that it is only when we doubt its existence that we even acknowledge that it exists at all

.

~ ‘Protraction’

Welton regularly employs a kind of Beckettian insistence that makes the reader question words’ values, including in the maths sense: the result of a calculation. For instance, in the sequence ‘Construction with stencil’, each poem begins with ‘Exactly’, and most end on the word ‘home.’

‘One’ begins:

Exactly as I’m saying it, the sunset comes

And ends:

The mind is multiplicity. I hope I’m home.

By the time you get to poem five it begins:

Exactly as exactly it exactly for

And ends:

Exactly of exactly home exactly mind.

‘Each move is dictated by the previous one – that is the meaning of order’ (Tom Stoppard, Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead). How we arrange words becomes what we mean.

This brings Oulipo to mind – constraint as a means to a poetic end – but for me Welton’s work feels more organic than that. He’s not purely a curator of outcomes, dissociated from the words the experiments produce. He works with words more as a painter aligns colours to interact. Personality and sensuality, as well as mechanics, conduct the experiments: ‘with love and logic’ as the monkey in the mind.

‘Poem in 72 words’ is a good example. Six stanzas of six lines each in strict ‘mechanical’ rotation. The first three stanzas show the pattern:

Roosters roost

Swallows roost

Warblers roost

Ducks roost

Grouses roost

Crows roost

*

Roosters swallow

Swallows swallow

Warblers swallow

Ducks swallow

Grouses swallow

Crows swallow

*

Roosters warble

Swallows warble

Warblers warble

Ducks warble

Grouses warble

Crows warble

And so it continues, with ‘duck’, ‘grouse’ then ‘crow’ as the verb in each line. It’s a rigorous mathematical grid. Each verb stems from the noun. Each runs in strict rotational order down the line – Noun 1 Verb 1 / Noun 2 Verb 1 / Noun 3 Verb 1 etc. In stanza two: Noun 1 Verb 2 / Noun 2 Verb 2 / Noun 3 Verb 2. And so on. Asterisks signal this is not a continuous poem but a (mathematical and poetic) sequence. Nothing is missed out or glossed for effect.

Yet the bird’s names are carefully chosen to work well as verbs, and verbs that other birds can (mostly) conceivably do. The order appears carefully chosen. ‘Roost’ is naturalistic – something said of any bird that doesn’t draw attention to the word choice. It begins the poem. ‘Swallow’ is slightly odder, but true. At ‘warble’ things begin to blur. Roosters might (an echo of ‘wattle’ helping it along?). But a crow? This is in the middle of the poem. We end with a more naturalistic choice: ‘Roosters crow’ and it’s surely no accident that ‘Crows crow’ ends the poem (‘to cry out loudly, to boast or exult’).

Welton’s subconscious is clearly in play throughout the collection. Word-sound-associations are drawn from his experience and word hoard:

A delay, a diversion, a detour, a search

A dictator who earns what his citizens earn

A Jamaican, a German, a Chilean, a Turk

.

~ ‘I must say at first it was difficult work #2’

.

.

The crayfish, the mussels, the lobster

Dawdling into Bristol or Norwich

Pay me a postman’s salary

.

~ ‘DFW #2’

Personal editorial choices are made. The poems above have stanzas, capital letters to begin each line and for proper nouns, commas, but no full stops at the line ends – highlighting they’re not sentences, but sense units (‘Construction[s] with phrases’). The thought-gaps between stanzas are Welton’s own breath-taking, pause-making. This element of the personal enriched the work for me. How the mind leaps about and what it feeds on.

Occasionally the generator for the poem overtakes compelling content, risking a mechanical feel (‘I’m wondering what’s for supper ‘cause I had no lunch’). And I sometimes found it difficult to get beyond the surface of the poem. But in a way that’s part of the experiment. You have to go back and spend time with them.

Time is a key conundrum for Welton. At the level of each word and line, he attempts to work it out. What is this word/effect doing now, in this particular context? And now? And now? The following could almost be his poetics:

A thing at its time is a continuation of itself, and a thing after its time is

a continuation of itself; a thing is a continuation of the things within it,

and a thing is a continuation of the things around it

.

~ ‘Abstraction with instructions’

The second part of the book is taken up with ‘Melodies for the meanwhile’, a major sequence which puts Welton’s full toolbag of tricks to work. He tunes words and phrases up and down across 36 near-sonnets (six couplets each), playing them off each other like so many chords.

Some of the procedures in this sequence include: Each first line has a key verb: ‘We’re idling’, ‘We traded’, ‘the woman is weeding’. Each poem ends ‘and when we speak it’s as if we’re unsure we’ll be heard.’ Each title is ‘A [M-word-here] for the meanwhile’, i.e., a measure, modesty, methodology, manifesto, etc.

It’s telling that for the final poem, the all-important m-word in the title is ‘mayonnaise’, not ‘mortality’, ‘metonymy’ or ‘meaninglessness’. It’s thick and sludgy, used to add flavour, droll:

………………………………….. [we] keep each other talking until

the weaselly stuff’s all been said, and while we’re perceptively

.

incisive on how the thing that makes a thing a thing is a matter of

activity, we don’t necessarily recognise the tension between things,

.

and we act as if we’re distracted by the insects in the path. The shadows

curdle together and our moods become

.

less decisive.

‘Melodies for the meanwhile’ amplifies one of the key hallmarks of Welton’s thought-provoking and rewarding project, that what we read and what we know are never settled. The leading verb in the final poem is ‘blunder’, followed up by ‘we fumble’, ‘our decisions feel unintelligible’. Who, what and where are we – where words lead us and leave us? How do we make decisions, or have opinions? How do we engage with the world? What are we governed by? These feel like important considerations as we embark on 2017.

Reviews are a new initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at – [email protected].

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.