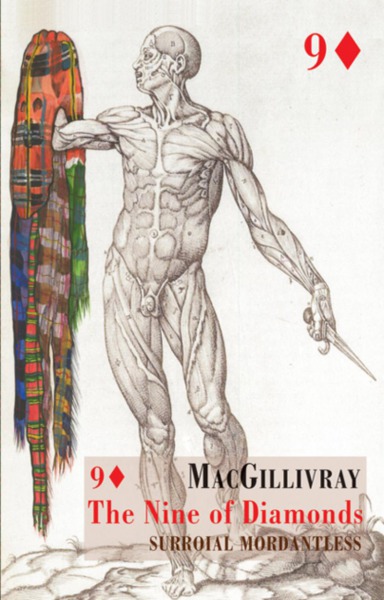

What do you do with three hundred years of Scottish history, a tarot deck and a battalion of European surrealist artists? If you’re MacGillivray, a multi-disciplinary artist exploring the Highland psyche, you make The Nine of Diamonds, Surroial Mordantless, her second collection, and first under the Bloodaxe imprint.

Surroil Mordantless explores the legacy of ‘The Butcher’, aka the Duke of Cumberland, who prior to the battle of Culloden gave the hurried order, scribbled on a playing card – the titular nine of diamonds – for “no quarter to be given” to men on the battlefield (i.e., take no prisoners). Since then, this card has been known as the Curse of Scotland.

Most revealingly, the book was written in Skye during the the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, when attempts to define Scottish identity took a global stage. With this background in mind, Macgillvray’s perspective is at once refreshingly original and enticingly other:

Come upon me! Come upon me in such a darkness!

Take me by my very eyes – secede!

Secede the now departing, granular dark, whose substance fades sheerly now,

in acquiescence to your burnished arrival.

Structured in nine ‘Paces‘ of nine poems each, the book explores many different physical and psychological landscapes, juxtaposing Highland and Scottish innovators against ancient and modern cultures and artistic traditions. In doing so, MacGillivray honours her vanquished ancestors, and even plays at assuming the role of the Butcher:

In winter, he prevaricates,

loosening the stakes

sucked the lens clean at your feet

sucked the clear marrow of hate

By the end of the collection we are brought back to reality through the recess of a waterfall, via another one of Macgillvray’s terrifying visions:

I am terrified.

Waterfall tickling.

The red carpet at my feet descends to hell

and rises up again in a black rash

of glittering frozen road.

Both the vital motif of the deer and the cultural centrality of the Gaeltachd (a word used to denote Gaelic-speaking regions) are immediately established in the first ‘Pace’, Suit of the Gaelic Garden of the Dead ‘where vultures fang[take]bone on the sandalwood trail, / fang leaky meat from the old gang dule, / skulk the dusted dream tooth pile.’

This deer canters on through the entire text – witness, victim and accuser of the Butcher’s callousness ‘he has leapt in the womb of his country, bucket bound / with slops’. ‘Surroial Mordantless’ refers to the stag’s predicament: ‘Surroyal’ is a critical part of the antler mass; mordant is a dye fixative. Surroial Mordantless witnesses the wounded stag, whose antlers continue to grow but who cannot fix them, give them form, structure and stability. It also witnesses the dye of Culloden’s lost and of continued bloodshed after the 1745 rebellion.

‘Surroial’ of course sounds like ‘Surreal’, and it’s no accident. The collection taps in to surrealist European traditions and juxtaposes them against Highland culture. The whole piece could be read as a dream, trance or vision. At the very beginning of the book, a text from Dwelly’s Scottish Gaelic Dictionary outlines ‘taghairm’ – the Highland tradition of sending an elder, mantled in a fresh stag or ox hide, to contemplate ‘any important question concerning futurity’.

Surroial Mordantless combines references to Breton, Duchamp and Gascoyne, as well as to Vaslav Nijinsky’s journals and Mallarmé based performances. This background is illuminated by extensive notes – many of the references would have been hard to ascertain without them, and belies a rigorous method to MacGiilivray’s madness.

As well as this international perspective, MacGillivray’s ambitions are intra-national, combining the three languages of Scotland. Whilst the dominant weave of the text is English, there is a Gaelic colour to the entire landscape. With the intention of straddling the Highland/Lowland divide, the poet also judiciously uses medieval Scots from Henryson and Dunbar to bring to the piece extra flavour:

Where sweats the doe, auroras piked,

her panicked musculature,

shudders rustic at the wind’s young touch,

schadowed in her pelt.

Mellifluate she pours, the honey hour

ourgilt [gold-tinged], now lyant [grey] stands her wood.

Surroial Mordantless also skillfully and at times unsettlingly juxtaposes tarot and pagan imagery with the visceral witnessing of bloodshed and Christian imagery, particularly the cross. It’s as if MacGillivray is spellbound by the wounds of the Highland genocide. In this reading, the poem is an invocation, designed to heal those wounds and bring some sort of justice to the perpetrators.

The final three suits in particular explore this, through the men of the Crois Taireidh, nine teams of nine men tasked with spreading news of bloodshed through the glens by way of burning crosses, and the site of the Old High Church in Inverness, where Highland troops were held in the aftermath of Culloden before being executed in the Kirkyard:

Whose warmth can dissolve the sanguine leap?

Can create a new river of melted blood?

I am terrified.

Waterfall tickling.

The red carpet at my feet descends to hell

and rises up again in a black rash

of glittering frozen road.

The conclusion of the piece brings a circularity to MacGillivray’s act of inter-generational witness. Once more we are brought to a waterfall recess – but this one is no home to sprites and fairies:

I stand behind a frozen waterfall

comprised of universal blood.

A mirror and lens of suspended pain.

My reverse iteration: blood makes me the ghost

of my own slightly

moving form – frozen blood

dissuades my materialism.

This is a kind of antidote to romantic Highland discourses. The vast spaces and empty landscapes may be pleasing to the eye, but they were once home to people whose oppression has extended beyond their unmarked graves. The piece attempts to unfreeze the moment of their slaughter, to reanimate those whose collective lives have been written out of history.

Surroial Mordantless will not be to everyone’s tastes. If you’re likely to be offended by images of Christ chain smoking in downtown New York or growing flowers through his vulva, this won’t be your cup of tea. If however you like bold imagery, scope and fearless imagination, you won’t be disappointed here.

Scotland may or may not shake off the curse she was dealt by the Butcher at Culloden. In this collection, and its author, she has blessings to count.

Reviews are a new initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at [email protected].

You can

You can

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.