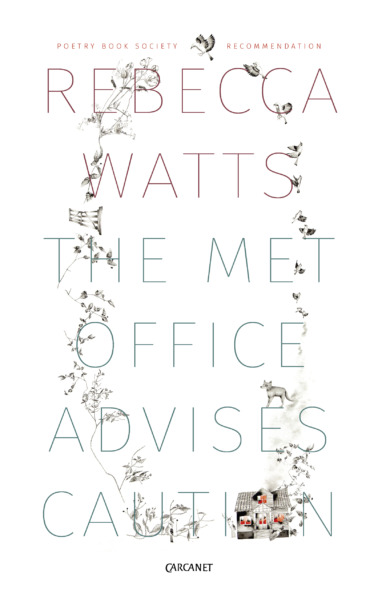

Reading Rebecca Watts’ first collection, I’m reminded of a phrase by D. M. Black who, talking about the Scottish poet Robert Garioch, advised readers to be careful in approaching his work, because beneath the quiet exterior ‘passions burn’. The same can be said of Watts’ initially disarming and unassuming poems that soon give way to wider and more thought-provoking vistas and harsher weather.

We get a strong sense of the frenetic creative mind underneath the lyrical exterior in the poem ‘Insomniac’, which filters poetic descriptions of the many things surging through the speaker’s head, only to reach the desperate conclusion:

[…] When

all I want

.

is everything to slot into

its proper place:

flat sky, round moon, straight path, dark river.

.

To lie down still as a woman between new sheets:

eyes closing effortlessly, mind empty

as a jar of water.

Watts’ exhausted pleas for things to be simple and the creative mind to be at a rest, which it can never achieve, is very reminiscent of the work of Iain Crichton Smith, a poet whose relationship with poetry was similarly fraught with a manic intensity; in his philosophical masterwork, Deer on the High Hills, Smith reaches the point of mental exhaustion and declares ‘stars are starry and rain is rainy / the stone is stony and the sun is sunny’.

With Watts we get this sense of the creative mind being strung out and pushed to its limits, often in poems that are ostensibly quiet, nature and landscape poems. In the title poem we see the poet trying to make sense of the non-human, like Iain Crichton Smith did with his deer, and finding that although anthropomorphism can help us relate to such things in often funny, absurd ways, it is ultimately inadequate, keeping us frozen out of a ‘secret knowledge’:

While the river turns up its collar and hurries along,

gulls line up to submit to the weather […]

.

A wheelie bin crosses the road without looking,

lands flat on its face on the other side, spilling its knowledge.

.

~ from ‘The Met Office Advises Caution’

There is a compelling dichotomy between the page / the book and the outside world that powers a number of these poems along. Watts turns experience into poetry rather like trying to decipher an arcane manuscript or illuminated page (it perhaps has something to do with the poet’s day job as a librarian). In fact, a number of poems are about dealing with ancient manuscripts, and the urge to decipher and understand things underscores much of the poetry, emanating from Watts’ ekphrastic and curatorial approach to her art. Take, for example, the opening poem, which instructs us to look at a tree. The speaker goes on to try and translate the meaning of the tree into language:

Below the tree

free-riding on the water

a shadow plays,

beguiling,

ripe for idolatry.

.

I believe the tree

and note it down as the answer

to its own question.

.

~ from ‘Realism’

In effect, ‘realism’ is whatever the observer makes of a certain thing. There can be a plurality of different realisms, each understood on the poet’s unique terms.

The difference between the mind’s inscape and the outer landscape comes across most starkly in ‘The Molecatcher’s Warning’ where the speaker interprets dead moles strung on a fence as something entirely other than what the molecatcher intended:

Only the moles remained,

strung on a barbed wire fence,

a dozen antiquated books forced open.

.

[…]

.

Read in me

they wanted to declare

how it all ends.

.

[…]

.

And their kin

can’t read anything

but earth.

Watts understands that it is either the gift or curse of the poet to try and see things in a new, different or forgotten light, and to do so means to be always asking questions, never taking the definitive version at face value and effectively never being at peace. The poet is haunted by the various possibilities of the interpretation of even the simplest of things, where all that poetry can ultimately hope to be is marginalia to the ‘official’ script.

There is a subtle tinge of jealousy to these poems, for people who can just take things as they are and not seek deeper answers or more taxing questions. In ‘Party’ we see how many of the speaker’s friends have blundered on into adult life like their parents before them, by becoming parents, while the poet is troubled by what they were and the role they are now playing: ‘My friends used to know how to party. / Today they’re all dressed up as mother’. In the witty poem ‘When you have a baby’ the speaker makes it clear she is not willing to sign up to being a godmother and all the small talk and baby names that go along with it.

The unwillingness, or more likely inability, to embrace a domestic family life is also powerfully expressed in ‘Pigeons’, where the speaker imagines a friend who has recently become a mother. They are tidying up the toys after a long day and catching their breath looking out of the window when a pigeon flies into the glass and kills itself. What is fascinating is that the mother character in the poem very matter-of-factly clears up the dead bird like disposing of a dirty nappy, and reads nothing into the event:

You’re no Darwin. You watch

obsessively; he obsessively watched

their habits & ways, and winced

as he laid his favourites down on the table

to administer the fatal dose of ether.

.

They gave him facts; he repaid them

with handwritten labels

and preservation in a national museum.

But things were different back then.

You have no need for a theory of everything.

It should be stressed here that the speaker is not suggesting that the mother in the poem is emotionally numb and the poet is highly sensitive, or that poets somehow occupy a special mystical place in life. Rather, what the poet seems to be arguing is the roles of poet and mother are as natural and self-generated as each other, but that to be a poet is to be something of an outsider, always possessed by an urge to make sense of things, rather than simply ‘being’. The mother watches obsessively what is happening for the sake of her child, but hasn’t the time or opportunity to then obsess about what has happened. Both poet and mother are active and they get their hands dirty and they both lack what the other has, so neither occupies a privileged position.

The idea of looking obsessively is present in many of these poems, even the ones that delve into the past, such as ‘Milk’ (an essay poem on Dr Johnson’s lifelong love of milk) and ‘Flesh & Bone’ which makes us look again at two Georgian era ‘freaks’ and surveys beyond what made them famous (in this instance, their corpulence):

Up to his neck in flesh, the famous fat man of Georgian England deposits himself on a double chair forever. Why we do not know, nor at what or whom he gazes roundly, and without acuity, as though such bulk necessitated sluggishness of perception also.

For Watts, poetry is anything but escapist and must confront the ugliest aspects of real life, such as ‘Letter from China’, which describes the historical abortion of female foetuses that are ‘like spilled water’ in favour of generations of ‘little emperors’ in Chinese culture. Other poems show the landscape and nature in an at times heavily Hughesian light, hostile to humankind and unforgiving, as in ‘The Hare’ where a struck hare dying on the road gazes all around ‘as though looking for an exit’.

There is also a meteorological theme underlying the collection (and its title). The weather-scape of the poems is an often changeable one; in the way Watts analyses and questions much of what surrounds her, mood becomes linked to the weather and in ‘Map’ ‘thoughts [are] like gales’. Weather is at times used like an elemental backdrop onto which ideas are projected, as in ‘Hawk-Eye’: ‘the wind is a wall / but / I see straight / through and the knowledge makes me / brazen against the white’.

Norman MacCaig once described poetry as a means of getting around stock or automatic responses to things that happen to us all and the clichéd language that goes along with this. I think Watts is doing just that in The Met Office Advises Caution. With a hawk-like vigilance to changes in patterns and an eye for detail against huge expanses of countryside and skyscape, Watts hunts for poems or poetic ideas. While Watts might feel like an outsider, cursed to be always on the obsessive lookout for deeper meanings and interpretations, making poems while her contemporaries stay indoors and act as home-makers, her eye for physical and emotional change ensures she will always be at the heart or core of things.

Reviews are a new initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at [email protected].

You can

You can

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.