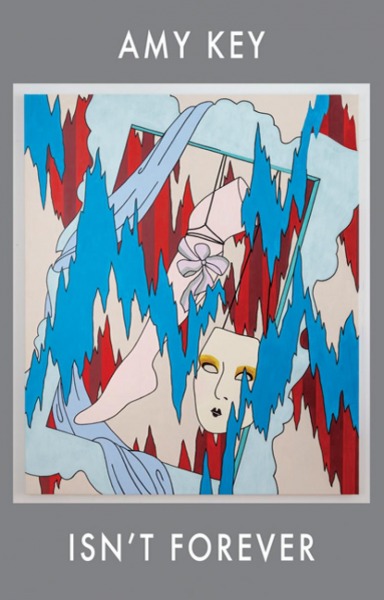

Isn’t Forever (Bloodaxe Books) is a moving and sincere song of mourning; a song which gathers impetus not through showiness but via a slow accrual of raw, untheatrical and many-layered sadnesses.

In ‘Lousy with unfuckedness, I dream’, Key writes:

[…] hello

microbes of my body / we sleep together / hello

cats / I make my bed daily / of the three types of

hair on the sheets / only one is human / I count

the bedrooms / I never had sex in / but there

were cars / wild woods / blackfly has got to all the

nasturtiums / you cannot dig up a grapevine / and

expect shelter to come / I am touched by your letter

/ writes a friend / you prevaricate desire / says

message / all this fucking / with no hands on me

Here, the voice shifts startlingly between performing ‘outwardly’ to curling up ‘inside’ to landing somewhere ‘in the middle.’ Upon re-reading it becomes impossible to tell which direction the voice speaks towards and from. One feels as though ‘I’ occupies constantly shifting sands and attempts to speak in many directions all at once.

This movement through shifting layers of speaking consciousness touches not only on the provisional, layered, fragmented experience of being a ‘self’, but also on the provisional, ever-changing experience of the ‘I’ which addresses another: variously, an ‘outer’ / ‘inner’ audience, an ‘outer’ / ‘inner’ ‘I’, and an ‘outer’ / ‘inner’ reader. And yet, Key suggests, there is no stable or fixed position to speak either towards or from, and so the multidirectionality of utterance produces many strata ‘within’ and ‘without’ the speaking ‘I.’

The question of who speaks from where, and to whom is explored in Key’s citational centos, or ‘collage’ poems. In ‘I wish I had invented the woman’ Key arranges phrases harvested from Yves Saint Laurent.

[…] I wish I had

known the indulgence of close contact with life; the encounter

of day for night. I have hunted down the false friendship

of the sun, sober. I emerged from solitude with many things,

spectacular concepts, all out of breath. The sea an extraordinary

denim. It’s a love story of everything I didn’t have.

The ‘scrapbooked’ effect of utterance in these centos augments the aphoristic, collage-like voicings of Key’s own work magnificently, and underlines the ‘citational’ nature of utterance both from ‘within’ and ‘without’ the speaking ‘I.’

As such, Key’s lines resemble piecemeal fragments of thought which strive for, but never quite reach, a sense of peace. Instead, the self is layered and restless – an effect of continuous, many-headed utterance. In ‘Gratuitously early the cold’ for instance, Key writes:

The shoreline was a fallen-down hem

I am interested in scenes where the sky & sea resemble one another

Tell me where the sea ends & the sky begins Ha! You cannot

Cows walked in single file towards me

I know it is common to be afraid in that situation; there is merit in caution

I have an announcement to make

Here, the fragmented voice produces an uncanny reading experience, where time seems to stand still; yet this stillness is offset by a feeling of continual displacement, an inability to settle.

These qualities and strategies of utterance feel to me like obsessive acts of mourning. The mind, roving and promiscuous, does not permit itself to be still; yet stasis is invoked by looping returns to an absent figure. Alongside this mournful, refracted ‘I’ is the question of women being observed from all directions.

Key’s women are acutely conscious of being observed by others, while also closely observing themselves. In ‘Delphine is having a mani-pedi’ we find:

The fidget of other people’s thoughts is too loud.

Delphine thrusts her hands into her robe in a way

that might be deemed sexual. Would someone watching

feel queasy? she thought. Like watching a man buckle

his belt as he leaves the bathroom. Like watching

a man watching a woman.

And in ‘The news reported she wore her body to the event’ the poet writes:

the crowd could not decide if her body was too much

or too little some demanded that her body amend itself

the person within her body was engaged in a gnarly debate

with her body and charges of slovenliness and pride

sloshed back and forth as might wine

carried when drunk

In these scenes we find women’s bodies at the mercy of both ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ policing. Delphine performs the ever-watchful ‘self-as-jury’, while ‘her body’ must face the ‘crowd-as-arbitrator.’ In both cases, women self-consciously view themselves from the ‘outside’ and internalise the outer gaze. Delphine explicitly questions it, while the speaker of ‘The news reported she wore her body to the event’ absorbs it fully and holds it close. This question of how women are viewed, surveyed and assessed – both from ‘without’ and ‘within’ – is central to Key’s restless, agitated ‘I.’

The ‘I’ and the eye which observes are atomised and adopt many different positions: thus, many performances for many audiences must be assembled simultaneously. Yet the impossibility of this task leads to a double-bind situation, in which the pressure to perform multiple selves summons stasis through self-interruptedness. The poet’s achievement lies in bringing performativity and inwardness to bear on both ‘outer’ and ‘inner’ stages, and in speaking through many strata of ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ voice with great success.

Part joyful, part melancholy; part ‘here’, part ‘not here’, the women in Isn’t Forever are ensnared in a kind of mourning trap. Key’s articulations of the mechanisms of this ‘mourning trap’ represent a moving, authoritative contribution to our contemporary poetic landscape, and this is a book I will return to again and again.

If you’d like to review for us or submit your publication for review, please contact Ali Lewis on [email protected] or Will Barrett on [email protected]

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.