The most incisive critical response I’ve encountered to Ailbhe Darcy’s recent work was when I posted a link to the first poem from Insistence on Twitter and Dominic Leonard replied saying ‘wow holy fuck’. That seems about right.

It’s not that that poem, ‘Ansel Adams’ Aspens’ (which refers to Ansel Adams’ photos of, yes, aspens, like this), is holy fuckish in any kind of revolutionary formal or intellectual way. It’s partly that it’s really, really good, but it’s also partly because of its technique of repeatedly restarting and readjusting, creating this effect of our being simultaneously overwhelmed by perspective and deprived of certainty. It’s disorientating, and an affective strategy supremely apt for our time, and one that Darcy recreates to great effect throughout the collection.

‘Ansel Adams’ Aspens’ first lines: ‘To tiny Ansel Adams, newly arrived on this earth, / the sky must seem a miracle’. Four tercets later, we get ‘To tiny Ansel Adams, newly arrived on this earth, / the sky must seem a matter of fact.’ Later on, ‘To tiny Ansel Adams, newly arrived on this earth, / the sky is what it is, taut with isness.’ The uncanny effect of that mutating foundation is heightened by a filmic quality: ‘Then the clouds would gather speed, // roll out again, and the camera pan down…’ Is this a poem about someone watching a film, or a representation of the film itself? Or of life, described metaphorically in cinematic terms? How do we tell the difference? Did those clouds actually gather speed, or was some unknown finger hitting fast forward? Whose story is it, structuring our experience of the world? At one point Adams is ‘kneeling on granite, choosing one filter / over another’; shortly afterwards, ‘Now the bright black sky / is Ansel Adams and Ansel Adams the filter.’

The miracle and the matter-of-fact are united in the perception of ‘isness’, and perception is mediated and remediated by the chopping, incompatible perspectives. It’s like Matrix Reloaded scripted by Edmund Husserl, and with photographs of quiet trees instead of a steampunk rave. The philosophical idea is that perception of a stable, noumenal haecceity – ‘isness’ – is a miracle attainable through an immediacy of perception that a poem (or a photograph, or any subject of a technocracy) can point at, but never embody. ‘It’s as though more and greater apparatus / were needed to recapture that first exposure’. Gaps open up between perception and perceived world. The idea has its political dimension – social media, fake news, the hyper-mediated society unable to relate to the natural world its ignorance is destroying – but also a phenomenological one, and it will be this ability to ride two horses at once which will define Darcy’s striking achievement.

The political angle is picked up again in the next poem, ‘Still’:

today I meant to be writing

about the weather— I mean I take a lot for granted—

like there will always be a metaphor—

but knotweed is the same every time—

nothing like words— I mean

to teach my son self-defence—

outdoorsy skills— how to be a survivor—

And here are the collection’s presiding themes: parents with a new child; looming environmental collapse; language being stretched out to breaking point (see those trailing em-dashes) in the vain attempt to bridge the awful gap between the joy of new life and the doom the natural world is increasingly coming to symbolise.

Although it’s never stated conclusively in the collection, the defining image of Insistence might be a young immigrant family, sitting on the porch of their American home and looking out at the darkening sky. The material of the collection circulates around this implied portrait, which is in its way symbolic of the relationship between the enclosed, personal us of the self or nuclear family and the distended, threatening other of the world.

That binary isn’t so simple for Darcy, though, and the threat of that otherness is always erupting out from within the mythical safety and regimentation of the family unit, even from within the mother-child relationship. There’s a stylistic tic throughout the book by which a gap is opened up in a usually seamless continuity. Even individual things cease to be identical with themselves; in one poem we find ‘Hobs simulacra for hobs’; in another we hear that ‘the future was annihilated by the future’s arrival.’; elsewhere ‘none of this business of history / having anything to do with itself.’ There are two subsequent poems both, uncannily, identically titled ‘After my son was born’. Perhaps the key recurrence of this eerie echo is in the poem ‘Mushrooms’:

How

in our time, the weather has changed, and the meaning

.

of weather. Machines pull machines from a bank of snow

The mushrooms of the poem are literal mushrooms until the eighteenth line, when we get ‘Come to mention / apocalypse (and we can’t seem to help it)’, at which point they become mushroom clouds, oneirically metonymising the end of the world through climate disaster, which attends upon the change not just in the weather, but on the meaning of weather.

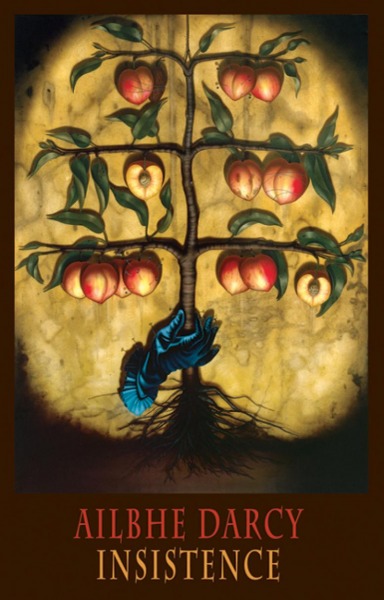

This exemplifies one of the central values of Insistence. This isn’t a book of ‘ecopoetry’, but it is a book which refuses to insulate its thinking-through of the significance of starting a family from the raging environmental destruction happening out beyond the back porch. Look at the cover image; a family tree having its fruit bound, sliced and impaled by the gloved hand itself nailed to the trunk.

That tree is summoned by the first section of the book’s long final piece, ‘Alphabet’, a poem borrowing the form of Inger Christensen’s alphabet, in which each section alliterates around the subsequent letter of the alphabet, but increases in length according to the Fibonacci sequence: 1 line for ‘a’, 2 lines for ‘b’, 3 lines for ‘c’, 5 lines for ‘d’, 8 lines, 13 lines…. The immediate difference here is that where Christensen’s poem makes a litany of things that exist, Darcy’s predicate throughout is insist (in– and not ex–…) so the first section is simply this: ‘apricot trees insist; apricot trees insist’.

From such a simple opening, things move quickly. The terms of the Fibonacci Sequence get further and further apart, so that while the second and third sections have only two and three lines respectively, section eleven (alliterating on the eleventh letter of the alphabet, k) has 144 lines. Darcy stops there – the section for z would need 196418 lines – but the gesture at vertiginous increase is sufficient. Remember that opening poem? ‘It’s as though more and greater apparatus / were needed to recapture that first exposure’

This rapid growth between sections calls to mind the kind of grossly overabundant growth of cancerous cells, out-of-control flora; that the Fibonacci Sequence dictates many patterns of natural development (in the spiral of a pinecone or a sunflower’s seeds) lends weight to this impression. This is the context in which Darcy slowly introduces irregularities into the poem, then. At first, each section lists things beginning with that sections letter, so section two runs:

but brand-names insist; and battlefields, battlefields;

bombs still insist; and blackface, and blackface

How quickly we’ve fallen from the purity of those apricot trees. But order’s present, at least, in the separation of the positive from the negative, and the formal constraints of the budding abecedary. But how quickly, once again, we falter. The third section:

concrete insists; cappuccinos; cathedrals

cancer-treatment centres, electric cigarettes,

corn syrup, cattle prods, automated cash machines

That last term is the first in a rush of increasingly frequent mutations from the form: in d we have ‘online dating services’, in e ‘dreams of widowhood and elk’, and longer sentences appear:

every

possibility insists, each future history,

here beneath our eiderdowns with earnest breath

earth insists its way into our future

With that last line, we’re taken back to the way the natural world intrudes into our personal lives, both in terms of the formal effects of global warming, but also at the level of thought. Further, our attention here is drawn to the fact that the human aspect of this poem’s form – the alphabetic listing – is degrading slowly as the poem goes on, but the natural aspect (the Fibonacci numbers of lines in each section) remains stainlessly above such matters.

The poem continues breaking down in this way, intermixing the insistence of hope with the insistence of doom in its exponentially expanding sections, circling back to the question of pregnancy, childbirth and childrearing, the breaking-down of the rules allowing for beauty as well as threat to find its way into the poem.

There really is far too much happening in this poem to summarise here, but the experience of reading it is, for me, deeply moving. The horror but also the beauty of humanity, the insistence of the good amongst the awful and the awful amongst the good; that unforgiving ambiguity of humanity, playing against the impassive natural backdrop we need, and are, and are destroying. In the words of one particularly devastating couplet, the first line of which is on one page and the second on the next, after a gulf of white space, ‘a person could insist […]

on the jointed boy incubating in my belly and forget

[page break]

we are not doomed yet.

A person could insist on their personal life. Only could, though. And after all, we are not doomed. Or rather, we are not doomed yet.

You can find out more about Insistence from Bloodaxe Books.

If you’d like to review for us or submit your publication for review, please contact Ali Lewis on [email protected] or Will Barrett on [email protected]

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.