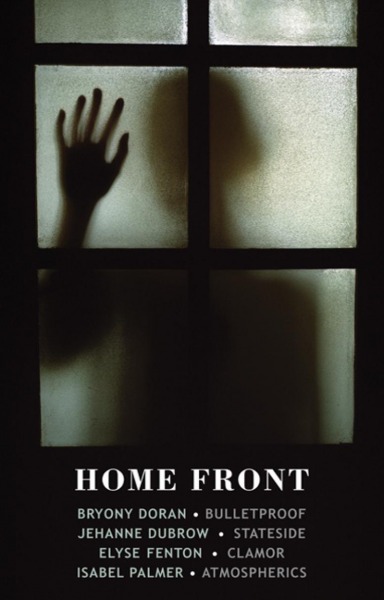

Home Front (Bloodaxe) is a quadrilogy of book-length sequences by four female writers – English mothers and American military wives – whose sons or lovers are enlisted. Each book is a mix of gravitas and (sometimes black) humour often found in true stories, showing the psychological interplay of managing the day to day whilst picturing loved ones being shot or drowned in visceral fantasies of war.

Isabel Palmer’s Atmospherics is a haunting opening. The overall tone is that of a teeth-gritting determination to hang on to sanity, illustrated by an obsession with dates documenting key moment of her son’s tour in Afghanistan. The language is ‘attentive / and exact as love,’ fraught yet meditative. Her son leads foot patrols: the most dangerous job in The British Army. As a way of coping, Palmer wrote weekly poems exploring communal experiences of soldiers, past and present, adopting the casual language of emails and military communications with families.

He calls us Dear Families as though he would like to shake our

hands, although personal responses are not expected. He is careful

to use the same subject description every time: Release-authorised:

Rifles Return.

This sense of distance and closeness, the spoken and unspoken is a key theme of a book that is fraught with internalized and imagined conversations between a mother and son.

I meant to say

whatever you did

was fine by me but I didn’t

and it wasn’t.

After he leaves, the mother is beset with violent fantasises, interpreting peril in every letter of his messages.

I knew you were in trouble

when you started putting x

.

on every message

as though your time was coming and going now

in dog years.

The collection ends as she ‘child-proofs’ the house after his return, locking away ‘knives’ hinting at her son’s trauma. ‘The weight of your own head / can overbalance you, like a TV / tipped over, news falling.’

The quiet, obsessive intensity of Atmospherics leaves you gasping for breath, which makes Bryony Doran’s Bulletproof a great respite, even though many of the same issues are recorded. The narrative in this sequence is a tightly wrought chronicle of home before, during and after her son’s tour of Afghanistan, with Doran and her son head-to-head in loving combat with nothing left unsaid:

On our landing there’s a bulletproof vest

I keep stubbing my toe on.

It doesn’t budge, unlike his helmet

that rolls like a decapitated head.

This wacky mix of images – a decapitated head rolling along an English landing is both darkly surreal and comical, perfectly encapsulating the tone of the book. Doran is a pacifist whose son has secretly signed up. She is suddenly a ‘part of the army, another dazed parent’, accepting that her son has his own life, and that her role as a mother is changing into a ‘hinterland – / uncharted territories of scrub – a no-man’s-land.’ We are subsumed into a kind of frantic tunnel vision as Doran faces the ‘unkindness of everyday repeating itself’, inviting the reader into her world with the immediacy of a great storyteller. Indeed, Bulletproof is full of close conversation, in which we as readers are treated more as friends than merely sympathetic neighbours:

I have a compulsion to tell strangers on trains,

My son is in Afghanistan.

A man, who sits next to me, on the way back

from Newcastle, asks how do I cope?

Everyone has an opinion.

Did you know

it’ll send him mental?

He’ll have to block everything out,

never get a proper night’s sleep again.

We often ‘overhear’ the son, giving the air of dialogue.

We’re in a big tent, ten of us, with mosquito nets.

Fucking cold at night.

.

Some parcels ‘ud be good, DVDs, some mags,

don’t take any notice of their advice

.

and some sweets and pens for the kids round here.

Little shits keep chucking stones.

The same gregarious generosity is found in Jehanne Dubrow’s exquisite Stateside. Focusing on ‘the fathoms of marriage,’ she explores enforced celibacy, loneliness and love that tastes of ‘syrup mixed with brine.’ The spouse of a serving US naval officer in the Persian Gulf, her ‘reflections from the shore’ often play with maritime terminology. The opening poem links marriage with a secure ship, setting the scene for the coming storm:

It means the movable stays tied.

Lockers hold shut. The waves don’t slide

a metal box across the decks,

or scatter screw like jacks, the sea

a rebellious child that wrecks

all tools which aren’t fastened tightly

or fixed.

At home, we say secure

when what we mean is letting go

of him. And even if we’re sure

he’s coming back, it’s hard to know:

the farther out the vessel drifts,

will its contents stay in place, or shift?

Dubrow traces the subtle shifts in marriage, using her own experiences and Penelope, the faithful wife of seafaring Odysseus. At times, the women become interchangeable: ‘Penelope, on a Diet,’ ‘Penelope Considers a New ‘Do,’ ‘At the Mall with Telemachus,’ and ‘Instructions for Other Penelopes.’ While the husband is away, sexuality becomes ‘a holy sacrifice … fruit kept edible on ice.’ The erotic nature of celibacy is portrayed beautifully as ‘the wait becomes my pulse, / come home, come home.’

…. How terrible to be a wife

made widow but still remain

married – what inaccessible terrain.

.

Whole regions that he used to kiss

are now abandoned land. What does she miss

the most? Without Odysseus

even her skin becomes extraneous

Physical and metaphorical pain merge within domestic practicalities as in ‘Tendinitis’:

Turns out that living alone results in pain.

He used to haul the groceries from the car,

uncork the cabernet, screw the lightbulb in,

…

don’t call the injury a metaphor

although it is, his absence, sharp, hard

as a knob of bone, and my fingers,

clenching and unclenching what they cannot hold.

These poems are fantastically engaging and honest, especially when discussing death, an ever-present possibility in their unconventional marriage: ‘all things sound like drowning if you listen.’ Even films catch her off guard: ‘Each movie is a training exercise, a scenario for how my husband dies.’ Stateside is both agonizing and thoroughly enjoyable with its mix of ethereal and blunt language:

Show me a guy

shipped overseas, and I’ll show you a wife

who sees disaster dropping from the sky.

Elyse Fenton is such a woman. Like Dubrow, Fenton is in love with a man on mission. Clamor is Fenton’s award-winning debut which explores the language used to talk about combat and, more personally, how a war which ‘can’t be finished or won’ affects a relationship long-term. Disturbing as the theme may be, what I liked most about this book is Fenton’s obvious love of military jargon and her vivid descriptions of the body. With her man ‘seven thousand miles’ away and ‘nine-months/ from home’ in Iraq, she creates vivid fantasies of her ‘heartthrob war hero.’

When I say you I have to mean

not some signified presence,

…

but your mouth & its live wetness, your tongue

& its intimate knowledge of flesh.

Her lover is a medic and their main form of contact is on the phone, creating a heightened sense of voice. She visualises his hands gathering the bodies of victims: ‘the ruptured scaffolding of ribs, the glistening skull, and no skin / left untended.’ Knowing the dangers of his environment she is alert to every nuance of his voice, ‘the feigned evenness’ and the ‘brief quaver.’ This attention to nuance is skilfully handled making the book a slow-burning concentration of the dark, psychological realities of war. On the phone, she relishes his technical jargon, and mediates on their meanings.

It happened again just now. One word

snagging like fabric on a barbed fence.

.

Concertina wire. You said: I didn’t see the body

hung on concertina wire. This was after the blast.

.

After you stood in the divot, both feet

in the dust’s new mouth and found no one alive.

…

I should say: love. I should say: go on.

But I’m stuck on concertina –

And later…

Yes, we did a corkscrew landing down

into the lit-up city, and I’m nodding

.

on my end, a little pleased by my own

insider’s knowledge of the way

planes avert danger by spiralling

deep into the coned centre of sky

.

deemed safe, and I can’t help but savour

the sound of the word – the tracer round

of its pronunciation – and the image –

a plane corkscrewing

.

down into the verdant green

neck of Bagdad’s bottle glass night

In the latter part of the book, the story shifts from fantasy to reality, exploring the tensions of living with a returned soldier. Like Isabel Palmer, Fenton’s poetry is tangential and exploratory, inviting re-reading. Despite having a similar narrative arc to the other collections, the story is told slant, focusing more deeply on the aftermath.

The cumulative effect of reading these collections back to back is sobering. Rooted in the varied domestic environments of the home front, they echo and respond to each other making individual experiences into collective rage, confusion, fear, patience, hope and love. These are not niche poems; they are written from the perspective of a range of women each caught up in war by association, which, in a way, we all are in these turbulent times. Homefront a book to be read by all who value what is good in humanity in the face of what is bad.

You can buy Home Front from the Bloodaxe website.

Reviews are a new initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at – [email protected].

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.