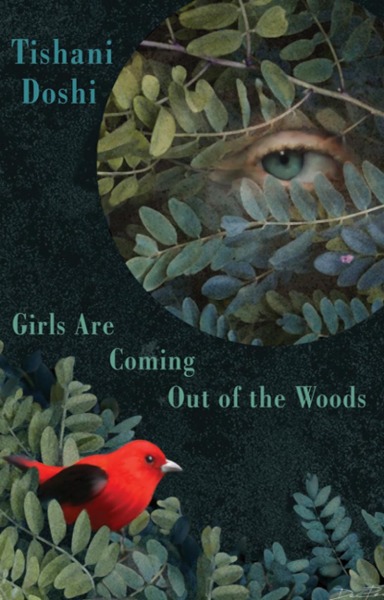

Evocations of dogs, rain, love letters, mouldy houses, dead girls, adolescent longing, and an understanding of the body’s mortality inform poet-dancer Tishani Doshi’s Girls Are Coming out of the Woods (Bloodaxe Books), an eerie world of both ruin and tenderness.

Conferred the Eric Gregory Award for Poetry and the Forward Prize for Best First Collection in 2006 for Countries of the Body, Doshi resumes her conversation in this startling collection with the body, its corporeal limits and inclinations towards the strange. The reader is taken on a surreal and often violent journey ‘backwards into the future’ as she states in the opening poem ‘Contract’ where she promises the reader that she ‘will forgo happiness’ and ‘lower my head into countless ovens’ in the hope ‘you may live / seized with wonder.’ Aside from setting the poet’s terms of engagement with the reader, the imagery used here, alluding to time-travel, beauty and the suicide of Sylvia Plath, demonstrates a sensibility that is alternatively ecstatic, enraged and ominous in nature.

Doshi, who is of Welsh and Gujarati descent, lives off the coast of South India in Tamil Nadu— the state from which other exceptional contemporary Indian poets such as Salma and Revathi Kutti also originate— and the sensory experience of living in that hot, languid region with its distinct culture and language pervades the collection. She locates much of the work in the city of Madras (now Chennai), the place where she was born, which she describes in ‘Honesty Hotel for Gents’ as ‘this dolorous city / of mine’ where ‘somewhere a temple with multiple chins is sheltering / a fishing bird and a million prevarications.’ The image of a temple as a distorted face is sufficiently disconcerting to understand that the poet’s relationship with the city is not a straightforward one. She continues:

We stamp and dance, drift from here to there, but a city

will come when we must rest in our contradictions,

spread the motor oil of gloom on our bones, give in

to waterlogged roads and cortèges of flowers.

Even though the poet uses the word ‘rest,’ it is in fact a feeling of restlessness that is skillfully brought to mind when preceded by ‘stamp’ and ‘dance’. The references to waterlogged roads and cortèges of flowers similarly invoke a sense of foreboding and decay that underscores the entire collection.

Desire and sexuality are also expressed, in terms which are intimately connected with death and ageing as well as humour. ‘Ode to Patrick Swayze’ is the strongest example of this contradictory play of emotions. Here, in the throes of a youthful crush at fourteen, the poet describes with a playful sense of rhythm, his ‘twang, the strut, the perfect proletarian / butt’ and the intense jealousy of girlhood rivalry:

I wanted revenge. I wanted to sue my breasts

for not living up to potential. I wanted Jennifer Grey

to meet with an unfortunate end and not have a love affair

with a ghost. At fourteen, I believed you’d given birth

to the word preternatural

The sharp use of line breaks, notably ‘I wanted Jennifer Grey / to meet with an unfortunate end’ and ‘I believed you’d given birth / to the word preternatural,’ teases at two alternative possibilities. First, that the poet also desired her nemesis Jennifer Grey. The second, the suggestion that Patrick Swayze had—impossibly—given birth, provides a contrast to the actor’s fatal illness with which the poem concludes. In this way Doshi deftly draws a full circle around birth and death.

In ‘Understanding My Fate in a Mexican Museum,’ one of the two sestinas in the collection, the poet upends the logic of time and chronology:

dear past and future selves—in time

we will resolve our joint concerns. Just leave me

for a moment with these Aztec gods to listen

at the crossroads. I may never hold creation in my skin

but I will always dream it. This is the fate I see

for my selves and me in a Mexican museum. In Mexico

I offered up my coat of skin for a chance to see

the Future Me. And in that raw, bedraggled light of Mexico

I saw a woman vanquishing the bones of time. And I listened.

Doshi addresses, and speaks from, a dizzying number of ‘selves’ in the penultimate stanza and envoi here. Future selves, past selves, current selves— they tussle in between both the internal rhythms of the poem and amongst the idols located in the museum, in the hope that some understanding and reconciliation can be achieved. The formal structure of the sestina with its repetition of end words provides a masterful contrast to the sensation of chaos that is created by these numerous identities.

It is the title poem for which however, one suspects, this collection will become known. Written as a response to the numerous cases of violence against women, and dedicated to her murdered friend Monika, Doshi speaks of:

[…] all the lies

whispered by strangers and swimming

coaches, and uncles, especially uncles,

who said spreading would be light

and easy, who put bullets in their chests

Despite its obvious register of defiance and anger that swells with each line, the poet enters here into territory of truly the absurd and macabre, describing girls ‘coming out of the woods / with panties tied around their lips’ who like ‘birds arrive / at morning windows—pecking / and humming, until all you can hear / is the smash of their minuscule hearts.’ With what other language may one speak of such unspeakable things?

Doshi recently performed a dance to this poem at Tara Arts in London drawing on her experience as a dancer with the Chandralekha troupe, named after the eminent Indian dancer. Performing poetry alongside dance may be somewhat unexpected but is not unusual if considered in the context of South India where devadasis, or courtesans, had been writing poetry to be performed with dance for at least several hundred years. In Doshi’s version, she accompanied a recording of the poem with mudras (hand gestures) relating to the yoni, a Sanskrit world referring to female energy and fertility, and drew on the language of the martial arts of Kalaripayattu, adopting much of the aesthetic of her teacher Chandralekha. The slap of the thigh with which the poetry-dance piece ends encapsulates the tension that is prescient in the collection: a compelling moment of anger and defiance, intersecting the power of the spoken word with that of the physical body.

If you’d like to review for us or submit your publication for review, please contact Ali Lewis on [email protected] or Will Barrett on [email protected]

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.