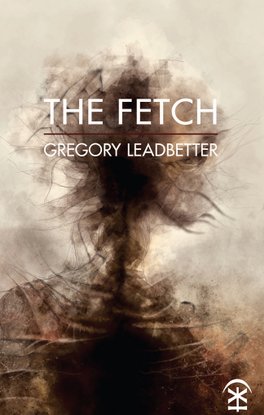

How do the dead function in poems? In Gregory Leadbetter’s quietly stunning debut The Fetch, the dead appear as echoes in the form of many ‘fetches’ – the apparition or double of a living person, usually an omen for impending death – that quietly haunt throughout.

The collection’s title poem begins suitably with noises in the night, which begs re-reading:

The dream that slammed the bedroom door

but didn’t break the film of sleep

to tell the time, or give me more

than broken promises to keep

to phantoms that were never there,

woke me just enough to know

that something was: the restless air,

the waveform of a note too low

to hear, a song to raise the dead.

I listened, and began to speak

as I am speaking now. My breath

condensed. I saw it slowly take

the outline of a child, afraid

of the dark of which it was made.

It is startling the way this sonnet’s list of things-that-go-bump-in-the-night gives way to the image of the speaker-as-child made from the darkness. The tercets unravel the regular iambic tetrameter of the quatrains in a way that seems to enact the exhaling breath. The form works wonderfully. Notice the cheeky reference to Robert Frost suggesting another way to read the poem, as an elegy to poetry itself.

Leadbetter’s elegiac tone lends itself well here; this is work that needs to be carefully read aloud. In ‘Deadheading’, a poem about pruning dying flowers, Leadbetter’s deft control of the iambic line lends the poem a cautions tone, mirroring the speaker’s careful tending to his plants:

I pare each stem with the pinch of a law

that couples the dead with the yet to be born

making way for plight and blossom

eyes still blind with earth to open

and when the sun falls on my neck

and servers my head from the morning air

it frees in the twofold tips of my fingers

a human bud, murmuring leaves

Yet, with such heedfulness there’s also a sense of threat: the speaker’s head is ‘severed’ by a guillotine of sunlight, eluding to the ‘self as shadowy apparition’ that is a key concern of the collection. It seems apt that the only punctuation in the entire poem is a single comma in the final line, a powerful caesura effectively deadheading the poem.

The book’s emotional core reaches full pitch during a sequence of poems for the poet’s ageing father. ‘Dendrites and Axons’ (the communicative relays of neurons) charts the father’s grappling with dementia in heartbreaking and thoughtful ways, as in the opening:

As a child, I could feel you think – see

your eyebrows in the rear-view mirror,

that motorway look – and play at

thinking myself. Now the noise

of what is missing from your mind

crowds and burrs in mine, leaves

no adequate thought for the day’s clue:

a photograph of the missing person

I’m going to visit this afternoon.

Throughout this sequence the world is being deconstructed. A task to draw a pentagon results in ‘Geometry itself broke open’. Deterioration of the mind leads to the death of day and night, as the speaker, distanced through a use of the second person tense, slowly comes to terms with the situation:

You tried to get out – as if every door

might lead beyond your mind, or back

to the dream of common truth: a marvel

all but lost to you. There was no way out

in fact, one but. You were caught in the glass:

that day you saw your Dad in the mirror

and knew you saw the dead.

The temptation here might have been to actually envision the dead returning to knock things over, and to offer themselves for comprehension as Rilke does in ‘Requiem for a Friend’, but Leadbetter tactfully navigates this heavily-written subject by sticking to his raison d’être – the presence and the numerous sightings of ‘the fetch’ in the everyday: water, mirrors, sounds and darkness. Rather than returning as warnings, or as heralds with urgent news, the sightings do not attempt to feign an authority beyond the grave, but serve themselves up as confirmations of living, as in ‘The Chase’, a poem observing the beginnings of a love affair. Here the final lines turn the passive voyeur into the poem’s agent, as though realizing he was really viewing himself all along:

He kissed her, as if for the first time

feeling for proof in her lips and her skin,

innocent of the hare cocked for the leap

back to the wild: when he looked in her eyes

I saw my reflection double and run.

This is Leadbetter’s real ability: hinting towards his terrible entities without focusing too heavily on any one. If ‘the fetch’ appears, it appears briefly, and in plain sight to remind him of his own mortality.

References to folklore appear more directly in the collection’s latter half, and are used to provide another lens through which to see ‘the fetch’, lending an appropriate alterity without becoming explicitly fantastic. In ‘Arcadia’ the horny goat-god Pan is thrillingly rendered as ‘a man-child with the head of a ram, / his brain a womb with Fallopian horns’. It is a poem of warning and presents another of Leadbetter’s many selves. In ‘Gibbet Lane’, another poem of advice, a mirror effect is created; beginning with statements describing what happens when you ‘Cut the rune on the hanged man’s tongue’, the poem ends with a transference: the ‘you’ in the poem becomes the hanged man. This time the omen of ‘the fetch’ has done what it’s supposed to do:

His lips move with your own.

Your question is his consummation

and his crime. The knowledge

taut at the hanged man’s neck

chokes on its own utterance

as he cuts the rune on your tongue.

For Leadbetter, the idea of ‘the fetch’ seems inexhaustible. From the quotidian and the occult, he expands on the theme in a series of poems about geology and the natural world, traversing landscapes haunted by memory. ‘Doggerland’ is an elegy to the sunken land that once connected Britain to mainland Europe; it evokes the land’s other drowned self, and could also be read as a Brexit poem. Then there’s a series of poems considering the Devonian Period, feverishly rendered in the transformation of human to sea creature in the prose poem, ‘Sea Change’:

…Your spine will thread you to the current. Think squid. Go deeper. Descale yourself as you cool into the dark. Mould yourself to the tide, reabsorb your architecture. Pale as you grow monstrous, a creature to tangle sperm whales in the drowning tentacles that leap from your head…

‘The Leap’ offers a similar reading of ‘the fetch’. Here, the focus is on the shoal, which paleontological evidence suggests evolved and moved onto land. The poem reverses the transformation of ‘Sea Change’, and the language used strikes a darkly seductive register, the shoal enticed by ‘the tug of warmth that tempts / them to the surface’, and struggling with the desire to break free of its bonds:

Something not yet fear, more

than the barely-begun

singularity in the gills that will

snatch at the air

in the seconds spent crushed

by the sun: waiting

skeleton-first in the crackle

of light, the giant

scorpion takes its shape,

the sudden darkness

remembered now, as something

not yet human

rushes

Aside from these metamorphic excursions, the human double is never far away. ‘Mirror Trick’ entwines a teenage flirtation with folkloric ritual with self-obsession and anxiety. Watching his reflection for the devil to appear actually seems to conjure the devil, albeit without pitchfork and cloven hooves, suggesting whom we should really fear is ourselves:

The trick was not to blink: only then

would the circuit hold and the surface

deepen with the reach of light. I have lived

some portion of my future since I saw

that figure form itself from what I am

in what was left of my reflection, a sealed

dimension in the silvering: a priest-hole

for something other than a priest to hide

in plain sight. Released, I knew him by those eyes

like mine, become at once too dark, too bright.

These many sightings and re-imaginings of ‘the fetch’ suggest we are never far from our maker. After a car accident in ‘The Departed’, the speaker’s many doppelgangers are spotted around the world, suggesting the closer we come to death, the more of our self, or soul, escapes. In a way, Leadbetter’s obsession is with self-preservation and through this, a renewal.

Reading The Fetch several times I’m sure there’s much I’ve missed and discoveries waiting to be gleaned from this tightly woven, finely tuned collection. It also occurred to me that Leadbeatter might have his own doubles. ‘This’, ‘Lessons for a Son’ and ‘Dendrites and Axons’ are reminiscent, in a good way, of Michael Donaghy’s ‘Present’ and ‘Haunts’, and if I were to place Leadbetter in the current contemporary poetry landscape, he’d fit nicely alongside a poet like Niall Campbell given his loving attention to the craft and form of the lyric poem and narrative verse. Although some may find Leadbetter’s careful and precise tone laborious, his reliance on metrical verse seems daring in comparison to the current vogue for experimentalism.

Taking the reader to a world both darkly mythical and accessible, like the bird in ‘Black-Necked Grebe’ that slips ‘behind the wind and water’, The Fetch manages to go elsewhere, to where we just might see our doppelganger, where we might learn what those dead have seen.

Reviews are a new initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at [email protected].

You can

You can

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.