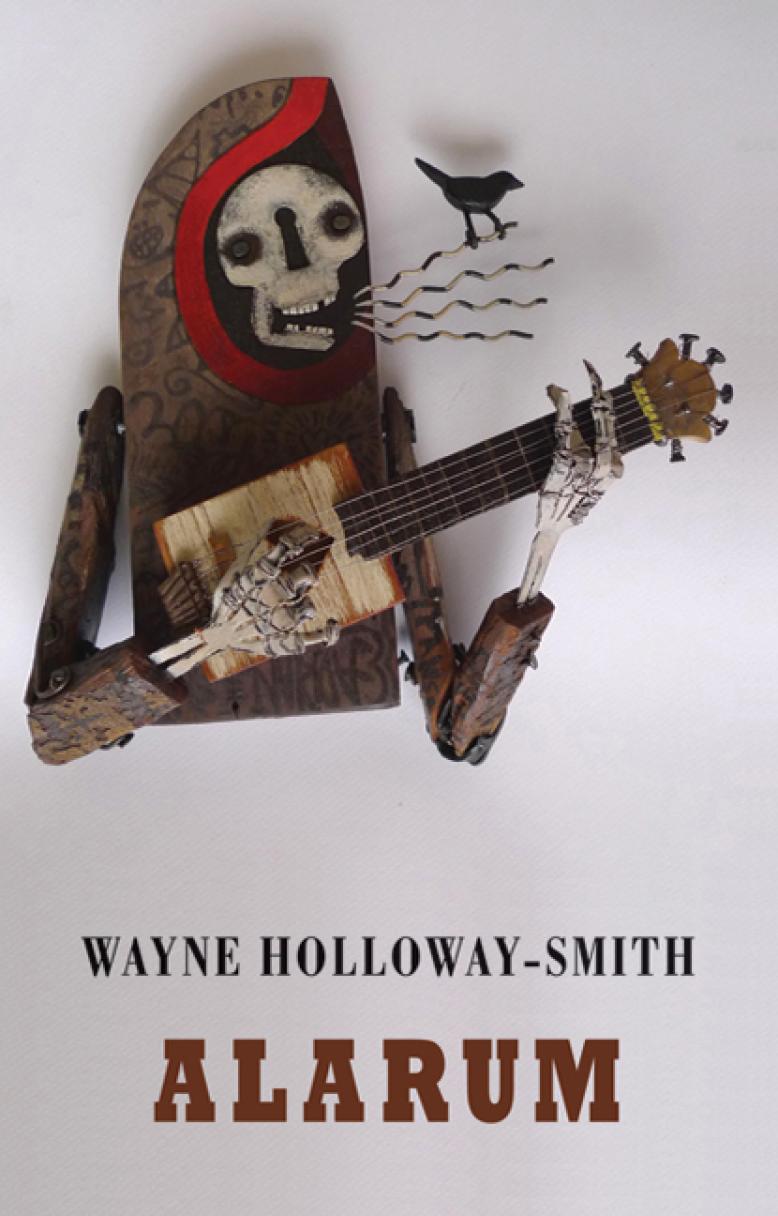

Whilst reviewing Wayne Holloway-Smith’s debut Alarum (Bloodaxe Books), I found myself reading sections aloud to friends in the pub, partly because Alarum is enviably good, but also because I couldn’t quite get my head around it. Hilarious and witty, it’s also terrifically sad, but wears its tragedy so lightly at first it’s hard to notice.

‘Doo-wop’, an elegy disguised as a poem about barbershop music, is an example of Holloway-Smith telling it slant. What I admire about this poem is how it tries to distract itself from grief:

There are so many things to run

and hurt yourself against.

Imagine that, for a moment

we’re in a time when you’ve not yet gone

and I’m telling you

sure as men in the fifties sing in high-pitched voices

that they really do want you to stay, girl.

There are so many ways to perform this genre.

Look shoo I’m bop di wop kicking

my bare feet about you

against the skirting boards, scuffing my toes

on the carpet and singing to the music

it’s making my manipulative longing for you

– softening it like those men at the key change –

to please not go

just a little bit longer under the ground.

It is a poem that is aware of being a poem and it doesn’t pretend otherwise. This self-aware approach is evident in the line ‘there are so many ways to perform this genre’, which refers, I assume, to the elegiac form, as well as to barbershop music. Through these digressions, the real grief seems distanced.

In ‘Sympathy for Toast’, a poem written in memory of the poet’s father, he creates a similar pretense. The poem explores the toasting of bread as a way of writing about the fragility of love. The academic attention he gives to bread hints towards an inexhaustible imagination:

[…] but toast has nothing save the properties it is made from and cannot barter only

hope that its colouring will carry enough currency just light enough a kind of

tanned white gold is best to be chosen cut further and eaten

In many cases Holloway-Smith is more comfortable risking conceit than being openly sincere. The final poem ‘Short’, is another example of this offbeat way of writing about the bigger themes of death and love originally. But he still makes you feel something without trying to yank on the heartstrings.

The whiskey in my dad’s bottle outlasts his body

I should be older than this by now

but the crushing simplicity of your hair

but I’m being played by Joseph Gordon-Levitt

in a movie about someone whose dad died

we could rob a bank here – I say in my American voice –

but he’d still be dead

At the centre of Alarum is ‘(Some Violence)’, a mediation on violence and masculinity in white, working class culture. In my view it’s a very substantial addition to the cannon of poems about working class culture by working class poets like Douglas Dunn (Terry Street) and Tony Harrison (The School of Eloquence).

Those familiar with the demands of a Creative Writing PhD (most institutions ask for a creative and critical project that is in dialogue) might recognise this poem as a creative self-reflective piece. Part poem, part essay, the sequence often commentates on Holloway-Smith’s own PhD on the same subject, and on his feelings towards being educated out of his class:

Somewhere everyone is beating and biting everybody else

In Swindon Eric Cantona stamps down hard

on the floor of a midfielder’s midriff

In other news refusing to sing

working-class love songs to other men

with other men and your dad is a type of violence

laughing at the back of your lungs

and knowing you will leave this arena for something

or knowing that you’ve already left it

cue: Degree AHRC funding PhD

scholarship for research on working-class men

and a shameful sort of understanding

The irony of a working class lad writing about working class culture in a way completely detached from the culture it seeks to investigate isn’t lost on the poet. The final section has him dining with a ‘celebrated poet’ whose wife points out how, by mastering the academic lexicon with which to dissect his subject, Holloway-Smith has murdered his ‘working class-self’ and can no longer be working class.

Tony Harrison also examines the alienating role of education in working class culture. A famous example is ‘Book Ends’ in which Harrison lists the cause of the differences between him and his working class father as ‘books, books, books’. Holloway-Smith, however, is much more self-deprecating, which is a strategy for writing about something serious without being too serious. I think he falls on the right side of detachment.

the joke is she says that now you understand words

like socio-symbolic and discursive values and have a certificate

to prove it you cannot any longer be working-class within

the dominant discursive values which have

enabled your socio-symbolic act and which no amount

of erasure can erase )

Given its blokey subject delivered playfully and skillfully, the sequence also makes me think of early Don Paterson. Whereas Paterson’s ‘An Elliptical Stylus’ takes a defiant stance, Holloway-Smith’s poem is less decided and is much more self-critical. It refines itself as it goes along as though showing its workings-out or thinking aloud on the page.

masculinity as our neighbour’s red and hairy knuckle

masculinity as my dad’s head knocked back

as a small man cursing

as shucked-off onions in the street

masculinity as next morning

my dad smoking crossed-legged on the doorstep

waiting for Henry to leave for work

Holloway-Smith has developed a style just as well-wrought as Paterson’s, but through the use of free-verse and the fashionable eschewing of punctuation for white space, it creates a less authoritative tone, which I assume is a deliberate attempt to get as far away as possible from any kind of received ‘poetry voice’.

Instead, Holloway-Smith has developed a voice through the creation of a personal symbolic register. In ‘(Some Violence)’ the dreaded ‘right knee’ becomes symbolic of a type of oppressive violence that is physical as well as mental. It varies from suggesting the dead leg the knee inflicts to evoking the ‘right knee of employment’ and ‘the right knee of the lunch hour’. One section has Holloway-Smith’s father punched by a neighbour called Henry. The next relives this image in a different but still violent context as ‘the threat of Henry’s wall’. This self-referential approach feels endlessly renewable and demonstrates Holloway-Smith’s creative resourcefulness.

This sense of personal symbolism also develops elsewhere in Alarum. Crows appear in many poems as stand-ins for anxiety and depression. ‘Everything is always sometimes broken’ sees crows fall out of the poet’s mind like a secret:

[…] I thought

.

I could trust you. It’s no big deal, there are people

you can even talk to about this on the telephone. There are still so many

crows up here, I tell them, and they need feeding, constant attention.

There’s a second reading of the crow here that suggests Holloway-Smith’s crows are symbolic of poetry itself (and a poetic image inescapable from Ted Hughes). Under this reading, the poem is a reflection on writing. The second section avoids being concrete, perhaps commenting on the maniacal pursuit of clarity associated with mainstream poetry:

If you could perhaps take all this and hold it for just a second,

up to the light, whatever it’s made of. If we could

be together in the eye of the awful thing, but together.

.

They sometimes have a different name for the crows,

but they can’t all of them be called that. In parks, people running

in vests, walking dogs. Some people can eat

.

and eat all day, then kiss someone. Others are hatching,

their eyes are nests for it. Some people are trying hard

not to let anything out into the daylight. Then,

wait. It’s no big deal…

There is much fine work in this collection of elusive and self-critical poems that are assured in their performance of uncertainty. The minute I think I understand a poem it shifts and does something else. From the cartoon-like ‘Worship Music’ with its crows from Dumbo singing at a wedding, to the clever personification of the phrase ‘No Worries’ as a white-van man with ‘a roll-up behind one ear’ promising ‘everything can definitely be sorted, mate’, Alarum is a refreshingly off-centre collection that builds upon a deeply personal symbolic register, which I hope will continue to flourish within Holloway-Smith’s work.

Reviews are a new initiative from the Poetry School. We invite (and pay) emerging poetry reviewers to focus their critical skills on the small press, pamphlet and indie publications that excite us the most. If you’d like to review us or submit your publications for review, contact Will Barrett at – [email protected].

You can

You can

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.