Danne Jobin interviews Pascale Petit, winner of the 2018 RSL Ondaatje Prize and co-founder of the Poetry School, about rainforests, mothers and fathers, and trauma.

Pascale Petit reads alongside co-founders Mimi Khalvati and Jane Duran at the celebratory event ‘21 Years of the Poetry School‘ at Poetry in Aldeburgh on Sunday 4th November.

Danne Jobin: You were a sculptor before you became a poet, and some of your literary work is shaped by art pieces, such as your collection about Frida Kahlo What the Water Gave Me. Your poems are often strongly visual, bearing an almost material quality. How does poetry communicate with other creative arts?

Pascale Petit: I’m so pleased you find my poems have a material quality because that’s what I’m after, making them into paintings, sculptures and installations, now that I don’t make sculptures and installations from raw materials. I have to be able to see a poem as well as hear it, and I think the visual arts can help to make the images more memorable, or see-able. As well as that physical and sensory quality, they can open up a poem, because artists can be very adventurous and playful, maybe more than me as a poet. The wonderful thing about poems is that though they can be physical entities, they are hidden away inside a book! I love that a collection is like a jewellery box full of colour and music that can be closed and kept secret.

But to be more specific, when I was writing Mama Amazonica I found the poems coming out were longish sequences, built up of small imagistic bursts of energy, such as “she’s a rainforest / in a straitjacket” (‘Jaguar Girl’), which is just one couplet in a two-and-a-half-page poem. That was a new development for me, and I worked at creating those pent-up bursts. But the fact is I love very short poems, and wanted to have some to punctuate the book, so it wasn’t too much hard work for the reader, and also for me reading them aloud at readings!

One week, a builder was working on our cottage. I shut myself in the bedroom and excitedly googled loads of contemporary taxidermy art images, and wrote about thirty very short poems, about seven each day! Not many made the final cut, but you can find some of them in the book, relief for the reader’s eye and heart hopefully.

Danne Jobin: You recently read at the conference on Poetry and Psychoanalysis in London, which focused on “writing shame.” How would you define the relationship between trauma, poetry, and therapy – and is there a risk of reducing poetry to its therapeutic function?

Pascale Petit: For me, the therapy is in the transformation of trauma into art. I’ve never been interested in just expressing the trauma straight, like a slice of life. What makes it redemptive is turning it into an artwork, changing it in the process. Mama Amazonica is (at least for me) a book where I love my mother, celebrate her, and show her power through the power and awe of nature at its most intense – in the tropical rainforest. Outside of that book there is the stark reality that we had a difficult relationship, that she didn’t mother me, or love me, and I could not love her. I find it incredible that I do love her in the book, feel warmth towards her, luxuriant warmth even. That is all down to the art – so if that is therapy, it feels more like magic! All life involves trauma, to varying degrees, and poetry can make sense of that, can transform it. I don’t find poems that are just about the trauma interesting, if there is no transformation. At heart, I suspect I’m more interested in the awe and wonder of nature, and bring human dramas into the natural world so as to make beings like trees, rivers and animals compelling.

I started writing when both my parents were alive. I published my first book Heart of a Deer (1998) just before my mother died. I kept the fact that I was having my first book published secret from her, because I had to write my poems and could not be censored. Nonetheless, this book has a lot of what I call ‘foliage’, obscuring the parents, abusive childhood, and traumas to a certain extent.

I did not know my father then; he had left when I was eight. But when I met him in Paris, after he made contact, and visited him while he was dying, I started to write my second book The Zoo Father (2001), directly in response to his reappearance. My mother was still alive, but she died a third of the way into the book. A year later he died of emphysema. He could only speak and read French and not English, and he had done terrible things to his family, so I felt I could write the poems, but I was glad he could not access them.

Even though I didn’t want to censor myself, I always tried to protect my mother from my work. She had really suffered and I did not wish to add to it. Once they had both died, yes, it made it easier for me to write about them. I have written two books about him, The Zoo Father and Fauverie, and two books about her, The Huntress and Mama Amazonica.

Danne Jobin: Your latest collection, Mama Amazonica, transposes imagery from the Amazon forest to talk about your mother, much as Fauverie allowed zoo animals from the Jardin des Plantes to merge with your father. Do you find that natural tropes are best suited to reflect personal experience? What drew you to these particular places to begin with?

Pascale Petit: I have been obsessed with the Amazon rainforest for twenty-five years, ever since I first saw a photo of Angel Falls in the book Waterfalls of the World, walked into a travel agent and asked how I could see this wonder in Venezuela’s Amazon region. I fell in love with everything about that landscape, visited it twice, trekked to the top of Mount Roraima and was canoed upriver to the base of the falls. The second, more ambitious trip was too hard for me and I fell ill for a few years. So I didn’t go back to the Amazon until 2016, when I went to the pristine lowland primary jungle of Tambopata National Reserve. Again I went twice, and on my second visit saw a jaguar!

I’m automatically drawn to natural tropes, but the nature is not just a trope, it is itself in my poems, as well as any metaphorical role it plays. It is nature that excites me, and of course different things will excite different poets, not everyone is crazy about trees and jaguars! But we humans are part of nature and it’s useful and perhaps even therapeutic to set our experiences in a natural, raw environment, where we once belonged in a more whole way.

Danne Jobin: In an interview with Anthony Huen, you say: “I suppose a poet ought to be an all-rounder and be able to write about anything, but that’s not how I work. I write about what I have to write about, not what I ought to write about.” Do your poems always emerge from such an urge, and is there a way in which you can seek them out?

Pascale Petit: There may be two urges my poems spring from – the personal dramas I must write about, and the impulse to describe awe of nature. I work best in solitude, on extended writing retreats. All of Fauverie and much of Mama Amazonica were written in Paris in rented rooms for one month at a time. MA was also drafted on a Gladstone’s Library month-long residency, and at home in my writing shed. If I sleep well, I like to start work very early in the morning, when the air is trance-like and fresh. Occasionally I write in response to commissions, and I enjoy the playfulness of that challenge – being given a subject, but it does have to feel like a poem I will include in the book I’m working on. I don’t dash them off – like the poems I have to write, I must connect with them in the depths.

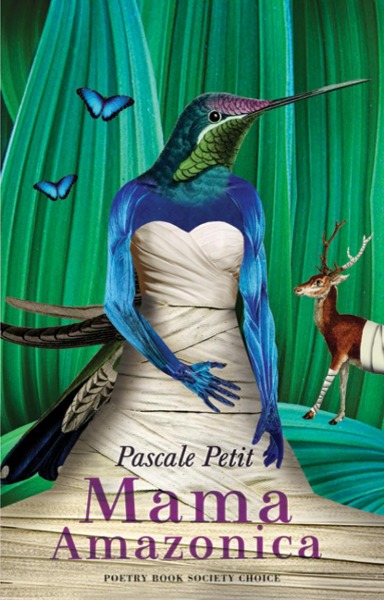

Pascale Petit’s seventh collection, Mama Amazonica (Bloodaxe), won the RSL Ondaatje Prize. She received a Cholmondeley Award in 2015 and was made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2018.

Pascale Petit’s seventh collection, Mama Amazonica (Bloodaxe), won the RSL Ondaatje Prize. She received a Cholmondeley Award in 2015 and was made a fellow of the Royal Society of Literature in 2018.

Danne Jobin is a PhD candidate in literature at the University of Kent and will be reading in Aldeburgh during the Queer Studio session. Earlier this year, they received an Arts Council bursary for a Free Read at the Literary Consultancy. Their poem “The Studio” is forthcoming in Tenebrae: A Journal of Poetics.

[…] GUARDIAN: 123 45678 LIDIA VIANUPLANET POETRYPOETRY ARCHIVEPOETRY EXTENSIONPOETRY SOCIETYPEONY MOONPOETRY SCHOOLPOETRY SHED PRAC CRIT: 123 PUBLISHERS WEEKLYRESEARCH GATERIZOMROYAL LITERARY FUNDROYAL SOCIETY OF […]