Because first of all, it’s not just I. Even in poetry, even the lonely writing on a lined pad or keypad. Even that has its communal moments. No one does anything on one’s own. And that goes for writing, too.

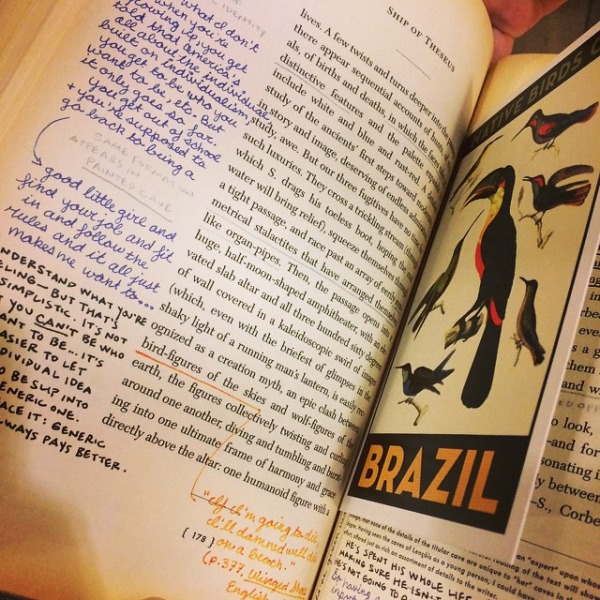

When I read a book of poems that move me, I know I am moved when I begin to poem back. A marginalia conversation. Writing, we know, can be a form of communication—with ourselves if it’s a private journal; with others if we publish. On one hand there is the desire to live among the diction and musicality of others, but also there is the desire for others to live within our voice and music. For me, literature, the creating of it and the consumption of it, has always been about communication. Not only with myself, for it is that. Not only with future readers, for it is that, too. But also for communicating with other writers—living and dead. I write in my books; I write to my books. The books of poems I own are sometimes covered with my own proto-poems…my turn in the dialogue I am having with this poet, with poetry itself.

We often read poetry written by the dead and this conversation with the dead is a vital part of becoming a writer. But it is a different kind of pleasure to converse, via poetry, with the living, and more over, with the living who we have seen or might see in their own living bodies. I had read books written by people now dead. Those were the white, the early Europeans, the old Americans of my grammar school education. In my own hope to find Caribbean writing, for I am a Caribbean writer, I had discovered more dead writers, these with bodies born in the Caribbean or of Caribbean parentage. Some white, some black and brown. I had also found poets who were living—but somewhere inaccessible to me at the time: Toronto. Nigeria. Jamaica. India. Then I met a living poet and I bought her book.

I didn’t understand then what that might mean, to be able to converse with the person and then again with the person’s poetry. The poet was just beginning her career. She had written one book. Later, there would be many prizes, including the Pulitzer Prize but The Body’s Question, by Tracy K. Smith, had only just been published. I met Tracy at a writer’s conference. She was generous and personable. We talked. I bought her book. I read her book. This was the first time I had done such a thing. Then I poemed back to her poems. I had written in the margins of books before, but now it felt like I had opened a secret tube of communication. Tracy K. Smith was a living person, but she didn’t even know I was writing poems to the poems she had written. It felt intimate—and therefore a little creepy—and therefore a little shameful, a little thrilling.

Here are some lines from Smith’s “Serenade,” found in The Body’s Question:

And my body rings

With the ringing that wants to be answered.

As though I am a little drunk in the bones.

As though all along, my body has been waiting

To show me these trees, these nocturnal birds.

What I started tripping out on when I read this, was the idea of the body as its own mind. The body as a mind. The body as a soul. The body as a question and an answer. The body as a being of preference and plans. I heard and saw her subtle rhyming, that happens in almost couplet form. I felt the music of the “rings” and “ringing,” the repeated “As though,” the closeness of “trees” and “these” that didn’t quite create a pattern, but rather a little syncopated tapping from somewhere in the body of the poem. I was taken by the simple language that communicated such complexity—I had to read it twice to even understand the basics of it—though the words were easy and the grammar clear. What is the narrator doing in the poem? She is dancing, but she is also looking at birds in a tree. She is experiencing something in her body that otherwise might be caused by rum and reggae—a drunkenness and a ringing—but is being made even more profound by natural environment.

This is what I was responding to when I wrote in the margins of Tracy’s book. I, too, wondered about the body. In “Serenade” Hayes’s body is stripped to its almost basic verbs. It can ring, it can wait and show you. In this poem the body might also deny, or the body might glow. My preoccupations back when I read this poem were about grand emotions. I wanted to know: could the body love? Could the body know the truth that the mind lies about?

So I wrote this:

The poem that this would become is called “Body Logic” and is published in my own first poetry collection, Wife. The word “logic” actually comes from another book of poems I discovered soon after Smith—Hip Logic by Terrance Hayes. I didn’t need to honor either of these poets by using their titles in my own title, “Body Logic,” but I wanted to. I also didn’t need to note where my inspiration had come from, but I did want to further clarify that this poem was a communication, so I even added, “after Smith and Hayes” so anyone who wanted to know could know:

Body Logic

(after Smith and Hayes)

The body has its own

infant logic.

Its own way to know

if what you speak is true.

It knows where your hands have been.

The body has jokes on you.

The body lies, for real.

It will rat you out.

Give you a negative

when you least

expect it.

The body will fail you, it will betray you.

The body tells you this is love—but hold on,

that’s no lie after all.

Picture this, baby: the body’s on your side.

It will open you

and leave you open.

And you’ll have to read it

like a sonogram.

Smith’s poem was the initial inspiration for “Body Logic.” In “Body Logic,” I remained interested in the intrusion of one time rhyme or sometimes repeated language, but in revision I also moved away from her poem. In the final version of my poem I have refined the line breaks by disrupting the lines. The action of breaking lines at uncommon moments produced a kind of trigger for me that also enabled me to see where the unnecessary language might be. Hayes doesn’t dwaddle in unnecessary language. She strips the poem down to its simplicity. I attempt the same in “Body Logic,” but Smith and I arrive to it differently—our poems are visually and musically very different. The persona is also different. Hayes’ narrator is in love, but unencumbered by responsibility. My narrator isn’t sure if she’s in love, but still finds herself with some pressures—there is the imperative: “You’ll have to…”, and then of course there’s that sonogram.

So there is something to be said for those writers who share with us a common vocabulary, a familiar swagger. In my case, poets who know and use the music of the 90s. Poets for whom Basquiat is so in, so down, that his visual work is taken for granted when arising in our own. I think many poets do, eventually, find their contemporaries and start talk-writing into the artful chatter of the community.

For me it began with Tracy K. Smith. Which was just because she was the first one. She wasn’t a Caribbean poet, which is what I really hungering for then (and still), but she was a living poet who was concerned in part with things I was concerned about. Whose body and place in the world was not terribly unlike my body and my place. And now she is part of my personal cannon, despite the fact that I have on more than one occasion bumped into her, her living body, on the train. She is, these days, an established poet who has written four books, won the Pulitzer and been nominated for the Nation Book Award in the US. But when I first met her she was a young woman, like me. Her first book had just been published. My first book was in progress. She gave a reading, where I was in the audience. In the question and answer she said interesting things about poetry. Afterwards she spoke to me with generosity. I spoke back, I think, with eagerness and gratitude. I bought her book. I wrote back to the book. Some of that became a poem.

Tiphanie Yanique is the author of the novel, Land of Love and Drowning, which won the 2014 Flaherty-Dunnan First Novel Award from the Center for Fiction and the American Academy of Arts and Letters Rosenthal Family Foundation Award and was listed by NPR as one of the Best Book of 2014. She is also the author of a collection of stories, How to Escape from a Leper Colony, which won her a listing as one of the National Book Foundation’s 5Under35. BookPage listed Tiphanie as one of the 14 Women to watch out for in 2014. Her writing has won a Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers Award, a Pushcart Prize, a Fulbright Scholarship and an Academy of American Poet’s Prize. She has been listed by the Boston Globe as one of the sixteen cultural figures to watch out for and her writing has been published in the New York Times, Best African American Fiction, The Wall Street Journal, and American Short Fiction. Tiphanie is from the Virgin Islands and is a professor in the MFA program at the New School in New York City, where she is the 2015 recipient of the Distinguished Teaching Award. Her collection of poems, Wife, was published by Peepal Tree Press in November 2015 and is shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.