In Anne Carson’s essay The Gender of Sound (from Glass, Irony and God, printed as Glass and God in the UK edition, and strangely omitting The Gender of Sound altogether) she writes of ‘…the haunting garrulity of the nymph Echo (daughter of Iambe in Athenian legend) who is described by Sophokles as “the girl with no door on her mouth” (Philoktetes). Putting a door on the female mouth has been an important project of patriarchal culture from antiquity to the present day.’

I read those words a year or two ago and, not long after, I came across Mary Beard’s LRB lecture, The Public Voice of Women. The pieces shared historical examples and contemporary concerns, and their various images and ideas hung about in my brain, not least the arresting image of a girl with a door (or lack thereof) on her mouth.

This was around the time I was writing a final few poems for inclusion in my first collection, Beauty/Beauty. I’d found myself preoccupied by ideas about female experience and womanhood and also naturally leaning towards a slightly different way of writing – a more solitary way – probably a product of the manuscript being workshopped, looked over, edited and generally poked about. I essentially wanted to be left alone for a bit. It’s tricky to think of a way of saying that I ‘worried less about the reader’ without sounding conceited or detached – I don’t mean I cared less, I was just writing in a less self-conscious way.

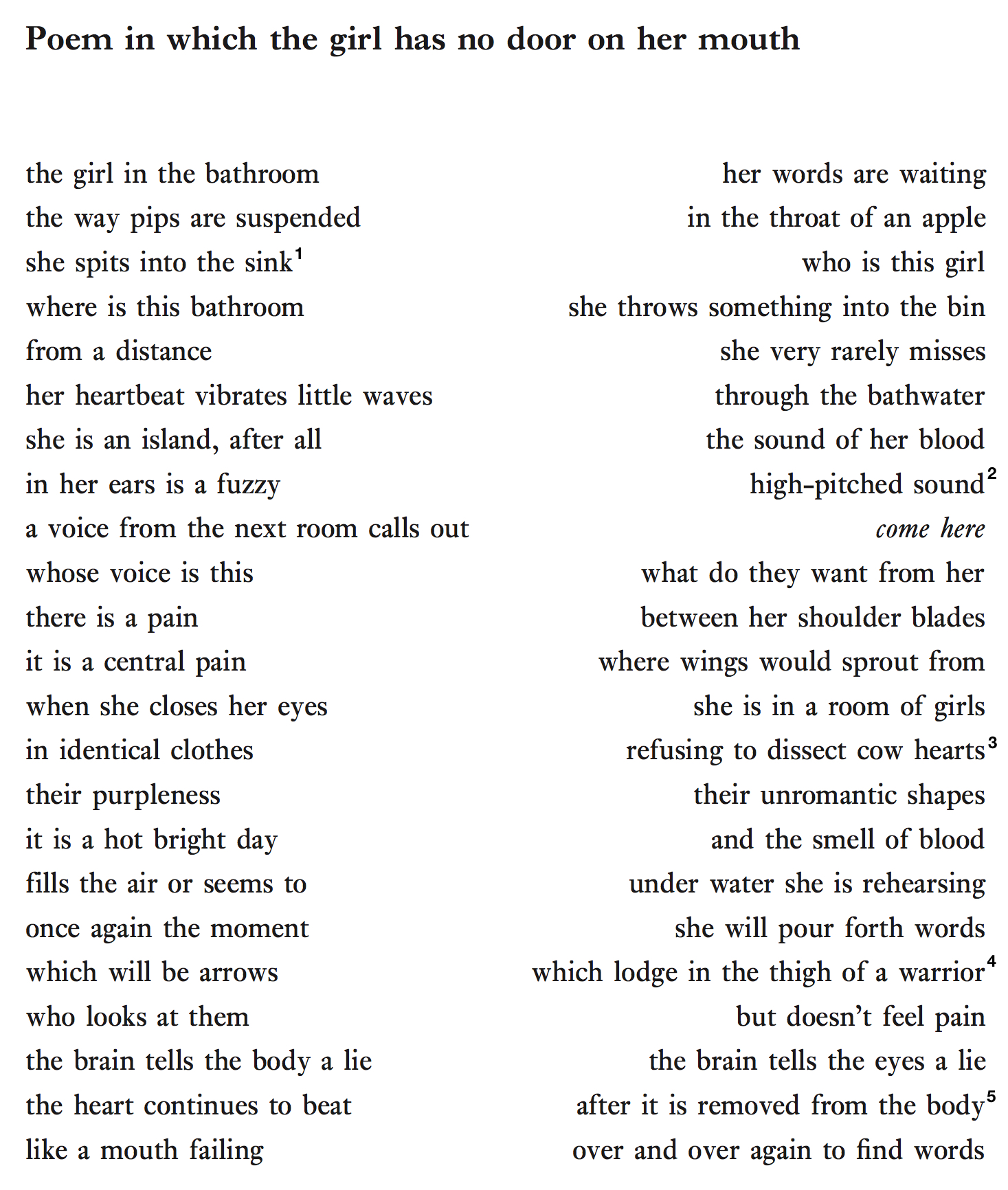

I tend to write poems quite suddenly and relatively fast, and looking into the methodology would be a scant exercise. ‘Poem in which the girl has no door on her mouth’ is more concrete in that it leans on The Gender of Sound itself as well as the Greek and Roman myth contained within it. Ordinarily I’d approach myth as subject matter with great caution, it having been done to death already, both brilliantly and badly. The Gender of Sound though, with its miscellany of sources and examples, was too brilliant (and relevant) not to steal from.

The title came before the poem in this case and it really helped me navigate my way through the writing. I also had a place in mind – the bathroom pictured – which gave shape to the world of the poem in my head. Both of these things aren’t usual for me.

I spend a lot of time in water, either swimming or in the bath, and I enjoy the experience of being separate from the rest of the world, either under the water surface or alone in the bathroom. I wanted to take a female in the bathroom as my starting point and work from there, exploring ideas about voice and expression as they came to me. I wrote the poem very quickly and made minimal edits afterwards. I suppose, broadly speaking, I took the action of the poem from the present, into myth, into (my) memory and back into myth again, quite fluidly and without any idea that was going to the shape of it.

Animal hearts (and hearts in general) are a recurring theme throughout my writing, so they presented themselves, as they tend to. I often have to edit out the hearts (they’d probably feature in every poem otherwise) but both Carson’s and Beard’s pieces reference historical accounts of the voices and sounds of women being likened to those of animals, and particularly the cow. I remembered being in a science lab at school and the majority of the class refusing to dissect the hearts. They smelt terrible. Our teacher, I think, totally believed that we’d eventually come round after being squeamish for a few minutes, but we were resolute to the end. Those two ideas fused for me at that point in the writing. It was also interesting to think about the ‘girliness’ of that act of defiance, how we were educated (at an all-girls school) with certain ideas about being ladylike, what was expected/accepted, how we perpetuated those ideas, and so on.

The final (and most significant) edit I made was to change the form. In its first outing on Poems in Which the layout and structure was more conventional, which didn’t feel was really working with the poem. I wanted to be a little more sparse, more disjointed, with the white space in the middle being reminiscent of a bath, a neck (see footnote 1), empty space ready to be filled with words, empty space where women’s voices should be, or where those voices have been erased. I also wanted the poem to be split into two parts, with one part being what we say and the other what we wish we could say, the real and the imagined, the outside world and the other the internal world of desires and memory, the public voice and the internal voice.

The end of the poem needed to be violent in a way, for the words (not yet spoken) of this person to pour out, disrupt and damage Carson’s aforementioned ‘patriarchal culture’. In her LRB lecture, speaking of the public voice of women, Mary Beard says ‘For a start it doesn’t much matter what line you take as a woman, if you venture into traditional male territory, the abuse comes anyway. It’s not what you say that prompts it, it’s the fact you’re saying it.’ I wanted this abuse – so relentlessly and casually thrown at women – to be caught, turned around and thrown back again.

[1] in the throat of an apple / she spits into the sink – Fruit is a regular feature in my writing. I don’t know why, though I do love fruit. The mention of the throat here is to do both with speaking and also bearing in mind the axiom of ancient Greek and Roman medical theory and anatomical discussion that a woman has two mouths – the oral orifice and the sexual orifice – both denoted by the word stoma in Greek (os in Latin) with the addition of adverbs ano or kato to differentiate upper mouth from lower mouth. Both mouths are connected to the body by a neck and provide access to a hollow cavity, guarded by lips best kept closed. I was also particularly worried about my own throat problems at the time of writing, and preoccupied with the idea that my voice might very actually disappear. The spit is an offering from the mouth, an act of disgust/rejection, railing against what is considered ladylike, and a preface to the girl speaking which never happens in the poem, but will.

[2] in her ears is a fuzzy / high-pitched sound – I wanted to reference Aristotle’s claim that ‘the highpitched voice of the female is one evidence of her evil disposition, for creatures who are brave or just (like lions, bulls, roosters and the human male) have large deep voices.’ Instead I wanted to sound to be of the woman’s blood (boiling? singing?) and also to call to mind the fuzziness of water pressing into your ears.

[3] refusing to dissect cow hearts – Here one of my personal memories creeps into the poem. I wanted to revisit the heart (first introduced in the heartbeat earlier and which I had an idea might end the poem) and tie that in with ideas of girlhood and memory.

[4] which will be arrows / which lodge in the thigh of the warrior – ‘Artemis, a goddess herself notorious for the sounds that she makes – if we may just from her Homeric epithets. Athemis is called keladine, derived from the noun kelados which means a loud roaring noise as of wind of rushing water or the tumult of battle. Artemis is also called iocheaira which is usually etymologized to mean ‘”she who pours forth arrows” (from ios meaning “arrow”) but could just as well come from the exclamatory sound io and mean “she who pours forth the cry IO!”’ (The Gender of Sound)

[5] the heart continues to beat / after it is removed from the body – I read that a tortoises’s heart will beat for minutes, and sometimes hours, after it’s been removed from the body. I decided to watch some YouTube videos to see if this was true (it is) and couldn’t get the image out of my mind. They looked like little mouths trying to breathe or speak, or fish gasping. It’s a bleak image to end on, really, but there is hope that the heart carries on in the face of adversity, and I hope it’s implicit that the failing will have an end.

‘Poem in which the girl has no door on her mouth’ was originally published on Poems In Which in an earlier version, and is included in Rebecca’s first collection, Beauty/Beauty (Bloodaxe Books).

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.