I have a fair few books about writing poetry on my shelves, some more helpful and inspiring than others. They do seem to have one thing in common, though: while they spend plenty of time talking about the poetic line, they have nothing much to say about the stanza. They may discuss set forms of verse that use a particular stanza form, but they never really say what a stanza is for, or even why poems have them.

The idea that line breaks matter most of all for poetry is clearly widespread. In his book A Linguistic History of English Poetry, Richard Bradford goes as far as suggesting that it is the poetic line that fundamentally divides poetry from prose:

“I can tell you in crude but accurate terms how to recognise a poem: it is a structure whose formal common denominator – that which separates it from non-poetic discourse – is its division into lines.”

But what about the stanza? Wouldn’t it be more accurate to say that a poem is ‘a formal structure whose common denominator is its division into groups of lines?’ Open any book of poems at random and you will find plenty of evidence for this.

The origins of the stanza at its most basic (that is to say as a regular or irregular group of lines with white space in between) are rooted in the classical Greek tradition. What we would now understand as lyric poetry can be traced back to a way of performing in which an individual poet would accompany themselves on a lyre while they sang their verses. What we now call the stanza was a group of lines in a set metre whose pattern was repeated, most likely to be sung to the same repeated melody, like the pop lyrics of today. As Edward Hirsch points out, another word for stanza is ‘stave’, which hints at the musical origin. Anyone who has tried to speak a poem by heart will also understand the way that highly regular stanzas, with a clear metre and especially with rhyme, make texts easier to learn and to recite.

But why does any of this matter to poets today? Not many of us get asked to sing our verses, and I haven’t seen a lyre at an open mic for a while. Well, for one thing, it seems to me to be curious that the stanza is so little discussed: while any workshop group or poetry class worth its salt is likely to take a new writer to task over poorly executed line breaks, my experience is that stanza breaks get much less attention. From talking with other poets, I know that many construct stanzas according to their own feeling, not necessarily with any clear principles in mind. The veritable epidemic of poems written in non-rhyming couplets in contemporary poetry – surely the formal trend of our day – perhaps suggests a lack of certainty over what stanzas are really for, unless the poem is being written to a set form. And even within those set forms, is it just a matter of following a pattern, or do the stanzas themselves help to make meaning in particular ways?

us get asked to sing our verses, and I haven’t seen a lyre at an open mic for a while. Well, for one thing, it seems to me to be curious that the stanza is so little discussed: while any workshop group or poetry class worth its salt is likely to take a new writer to task over poorly executed line breaks, my experience is that stanza breaks get much less attention. From talking with other poets, I know that many construct stanzas according to their own feeling, not necessarily with any clear principles in mind. The veritable epidemic of poems written in non-rhyming couplets in contemporary poetry – surely the formal trend of our day – perhaps suggests a lack of certainty over what stanzas are really for, unless the poem is being written to a set form. And even within those set forms, is it just a matter of following a pattern, or do the stanzas themselves help to make meaning in particular ways?

I know that, in my own work, I’ve been guilty of a lack of care for the effects that stanzas can help us to create when we structure poems, which was one reason I was so keen to suggest this theme for a course to the Poetry School. Not only will the course provide participants with the space to think about these issues, and some useful examples to follow, but it will hopefully also be an opportunity to explore together what is, after all, the second significant structural element of poetry itself.

What I hope we will discover together will be roughly along these lines:

1. EVERY POEM HAS ITS OWN LOGIC, even if that is a surreal logic, and that logic implies the unfolding of ideas and images, throughout the length of a poem. Otherwise, you have a static poem, which is another way of saying that you have a dead poem. Thinking more carefully about stanzas as a key structural element can help you to keep your poems moving, and not necessarily in the directions your reader was expecting.

2. STANZAS ARE, at least in their original meaning in Italian, rooms, but also stopping places. Imagine your poem is like a house that others will visit. They will move from room to room and stop for a while in each. Because you have excellent taste, they will see that every room makes sense on its own terms (the carpet doesn’t clash with the curtains, the way that vase is positioned sets off that table beautifully). And yet, at the same time, when your visitors go to the next room, they feel like they are still in the same house: they haven’t just walked out of your 50s diner-style kitchen into an oak-panelled dining room. Each little unit makes sense, but so does the whole. So, keeping things moving in interesting ways from stanza to stanza doesn’t have to mean you lose coherence, if you build your stanzas well.

3. ADOPTING PARTICULAR STANZA FORMS can make you write in new and interesting ways, pushing you to unexpected places and developing your ideas and images in ways you hadn’t thought of before. Stanzas need not be an afterthought (just a way of dividing up the lines you have written into more or less even units so they look neat on the page), but can (and should!) be integral to the way you construct your poem.

4. EVEN IF YOU ARE NOT using established stanza forms, writing in free verse or in more experimental ways, stanzas don’t stop mattering, even if we are only talking about the grouping of lines on the white space of the page. All of the above still applies, and perhaps even more so.

I hope this has said enough to persuade you that taking the stanza seriously (and then taking this course) is not a dull and technical thing. As we move through the course, we will be looking at poets as diverse and Tennyson and Jorie Graham, for all of whom the questions I’ve raised above are vital questions. They should be for you, too.

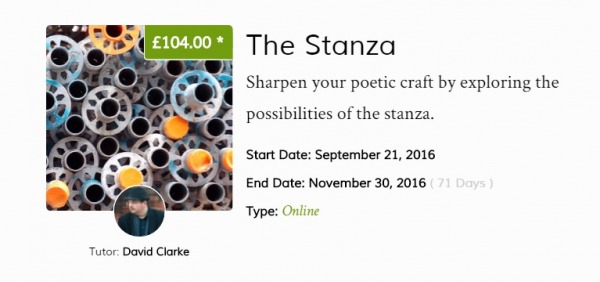

Want to understand and experiment with the structure of your poems? Join David Clarke’s online course The Stanza for Autumn 2016. Book online or ring us on 0207 582 1679.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.