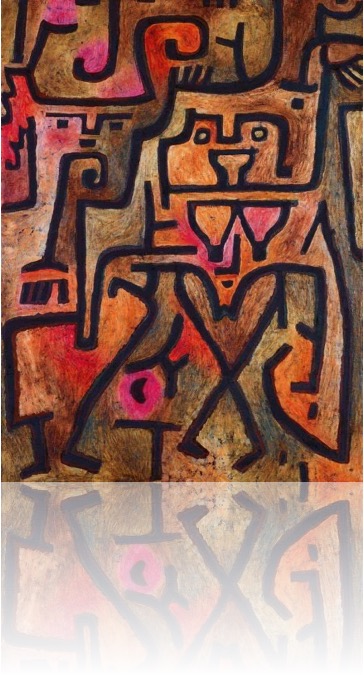

How can abstract art help poets? It makes us look and it makes us think, and it makes us think about our thoughts. It helps to steer us away from pre-existing categories. We cannot glance at it and then say ‘Nice goat’, or ‘Evocative seascape’, or ‘What a lovely cottage!’. Instead, we interact with the lines, forms and colours, our minds hovering over a range of possibilities. We register the medium. We see paint (or whatever the art work is made of). We can make notes about our shifting perceptions but we will not be able to offer a definitive conclusion about our experience of the art. We can celebrate the processes of interaction instead. We can trace the flicker of the here and now – we can turn it into art of our own. In some respects, we are able to collaborate with great artists while being fully engaged in our own creations.

Of course, we may want to find out some ‘facts’ as well. Where is this painting? What is it made of? Who made it? What were the circumstances of her life? When was it made? How does it relate to the history of painting, to society, to politics? But, for our purposes, the main concern is how we respond to the work, how our responses fluctuate, and how we allow the spirit of the painting to infuse and shape our own writing. This will be unique for every person. We respond with the whole of ourselves, our contexts and our histories.

There are two things we will try to avoid on this course. The first is making a straightforward description of the painting or sculpture. The second is writing a poem as if Modernism had never existed. In Britain, broadly speaking, poetry has lagged behind the other arts in terms of risk, playfulness and experimentation. But we will be trying things out, embracing process, avoiding traditional prescriptions. We will not care whether or not our poems fit into other people’s boxes. We will make it new.

One of the key concerns of Modernism and its various aftermaths was how to move on from styles of writing and creating which still relied upon a single, untroubled authorial voice, or a single visual perspective, the famous and infamous ‘I’! Of course, this was never to say that the poet’s perceptions and feelings could not generate the poetry. That would be impossible and undesirable. But there was a sense that art had to keep refreshing its relationships with reality, making them more subtle, complex and inclusive.

In this course we will think about orchestrating voices other than our own, experiences from far away in place and time, and the overlapping complexities and conflicts of location. Sometimes we will foreground language just as Jackson Pollock foregrounded paint. We will also be creating a longer text, or sequence of poems, which could well form the basis of a pamphlet or more extended collection. This will involve compositional and editorial crafting over a much broader canvas. Participants on this course will have the opportunity to explore and extend their writing methods, engage with exciting works of art, interact with like-minded poets and create a substantial body of new and forward-looking work.

The course runs from the middle of September until the middle of December 2020. Come and join us!

Peter Hughes, Snowdonia, July 2020

I would love to join this course, I am a painter as well as a poet I have had paintings sold at numerous exhibitions but going that step further would be exciting.

That’s great to hear, Justine. I think that this course might be sold out currently, but, if you email [email protected] they can add you to the waiting list. We also occasionally run courses twice, when there is enough demand.