Retiring to the canopy of the bedroom, turning on the bedside light, taking the big dictionary to bed, clutching the unabridged bulk, heavy with the weight of all the meanings between these covers, smoothing the thin sheets, thick with accented syllables—all are exercises in the conscious regimen of dreamers, who toss words on their tongues while turning illuminated pages. To go through all these motions and procedures, groping in the dark for an alluring word, is the poet’s nocturnal mission.

From Haryette Mullen’s ‘Sleeping with the Dictionary’

In the preface to his groundbreaking work A Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson describes himself as “a poet doomed at last to wake a lexicographer”; he realises that to reach towards creating that elusive, perfectly accurate dictionary definition is to “chase the sun”. Instead, he settles for writing ‘best fit’ definitions that will usefully delineate word meanings for speakers, writers, and translators.

A dictionary is an authoritative, practical, functional aid to expression and understanding. It aims to record existing language use, not to create new meanings. Poets, though, aren’t constrained by such practical considerations. For the poet, a dictionary can be a deliciously rich source of building material and inspiration, a sort of collective linguistic ‘bible’ that attempts to track, classify and hold on to the ways we communicate through language. As Robert Pinsky explains in the notes to his 2007 dictionary-focused poetry collection Gulf Music, “…any word – is an assembly of countless voices that have uttered it or thought about it or forgotten it.”

But language is often, as both poets and lexicographers know, a pretty blunt instrument. As Charles Simic says, “Poetry tries to bridge the abyss lying between the name and the thing. That language is a problem is no news to poets”. Poetry often attempts to bridge the gap between experience and the words we have to describe it by using and focusing on less ‘rational’ or translatable aspects of language such as form, rhythm, and sound-sense, and by using culturally specific metaphor and connotation, and deviations from the usual rules of language.

So while lexicographers are largely concerned with documenting and delineating language, poets may stretch a language to its limits, subverting and re-making it as part of a process of change and renewal. By evoking the dictionary, by using dictionary definition form or register, or incorporating dialect words or neologisms, the poet can draw attention to the idea of meaning as slippery, shifting, evolving, and/or potentially imprecise.

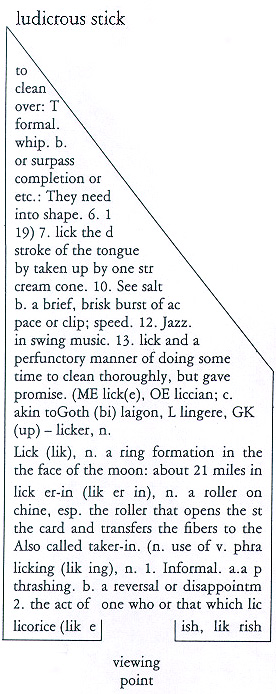

Tina Darragh, ‘ludicrous stick’

The dictionary of a language acts as a sort of collective, authoritative ‘guardian of the cultural tradition’. When we want to know if a word exists, or whether we know it correctly, we look it up in the dictionary. But what happens if we don’t feel represented by the dictionary of our own language? Lexicographers seek to record and describe language rather than control it but, as author and lexicographer Jonothan Green observes, “All lexicographers… who are the mouthpieces of a social class, the instruments of an ideology, no doubt believe that they objectively represent a set of forms. But there is no objectivity, no picture so accurate as to eliminate the model”. While language dictionaries must aim towards an ideal of collective ‘objectivity’, poetry is free to point at (and play with) what the dictionary leaves out, or can’t quite reach.

For example, in his 2010 collection A Light Song of Light, Kei Miller’s poem ‘Some Definitions for Light (I)’ plays with the idea of etymology and history, and of meanings composed from root words. “Photomania” is described like this: “an obsession with light – in 1974 a man was found sweating in his small room surrounded by a congregation of lamps, 137 bulbs burning, even daring the day he was trying to create.” Miller uses a very specific image to illustrate his invented word, “photomania”. We are given an exact year, an exact number of bulbs. There is “a congregation” of lamps. This dazzling, revelatory or religious and troubling sense of the word ‘light’ recurs throughout the poem.

So Miller’s definitions collectively point towards a very particular sort of light – one which he has no single word for. The writing shifts between a more general, informational and ‘objective’ dictionary-definition style – “Photophobia – the fear of light” – and a more individualistic, playful, narrative and poetic one: “photophobics hide in the shadows; their eyes hurt. The photophobic cannot read this; they are at risk of going blind.”

Jen Hadfield’s poem ‘Gish’ from her 2008 collection Nigh No Place defines a little-known or invented word. The examples that make up the definition play with the word’s sound-sense and its similarity to other words. So ‘Gish,’ with its short, hard sound and the ‘sh’ that reminds us of water becomes “Gish, noun: a channel of water strained through the wet red grass of a Fair Isle field, where a conger eel, like a swathe of gleaming liquorice, might thresh till nightfall.” The poem celebrates the specificity of place in dialect words, and the value of linguistic diversity.

In dialect, words may come about (or be maintained) out of a need to articulate place and culture-specific experience such as experience of a particular landscape, of particular weather or particular work. Such words, and their meanings, can be specific to small communities, and even to families (as demonstrated in Paul Muldoon’s poem ‘Quoof’). Jen Hadfield’s definition for ‘Gish’ draws attention to the ways in which the dictionary as authority can limit what’s perceived as acceptable or ‘proper’ language through the exclusion of taboo, dialect, or newly-coined words. By using the dictionary definition form in this way, the poem both celebrates and subverts the lexicographer’s role.

So – poets’ engagement with dictionaries can subvert, celebrate and play with the unreachable ideal of language as a transparent common code by drawing attention to the individual human voice and its fantastically messy subjectivities. Dictionary focused poetry can allow the poet (and encourage the reader) to re-insert their own voice – their individual, lived experience – into the cultural lexicon, actively participating in the making and re-making of the language.

Think your poetic praxis could do with an injection of word nerdery? Book your place on Kate’s new online course New Definitions and Neologisms: the Poetry of Dictionaries or ring us on 0207 582 1679.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.