I remember giving a set of poems at ‘Reading the Leaves’, a night in Tchai Ovna in Glasgow where I liked to try out new work alongside other poets, novelists and writers. The poems in my set were mostly new, and seemed to arise independently of one another, but a striking commonality revealed itself as I was reading.

‘All my poems seem to have a watery theme’ I said to Nalini Paul, the tireless organiser of what was one of the few outlets for writers of its day. ‘Well, you do come from an island’ she observed.

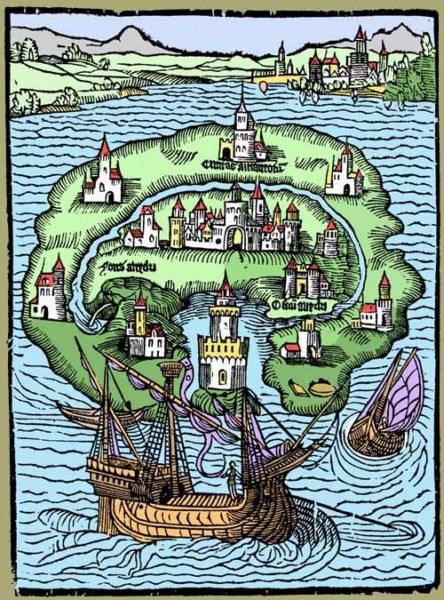

The Island of Utopia, from the original book frontispiece, 1563

It seemed obvious, but it hadn’t occurred to me that my island origins – Yell in Shetland – would influence the nature of my work. Some years after this, I was lucky enough to be included in Kevin MacNeill’s remarkable anthology These Islands We Sing, the title playing on George MacKay Brown’s deft autobiographical piece ‘For My Island I Sing’. Kevin’s aim with the anthology was seemingly straightforward – having enjoyed an extended residency in Shetland, he wanted to collect poetry from all of Scotland’s islands. He had expected to be publishing only the latest in a line of such anthologies, but later found that his collection was the first such gathering of the poetry of the Scottish islands.

Fast forward past a first collection for myself and, the growth of The Island Review, an online magazine devoted to all things island literature and I had the outrageous fortune of taking part in the 2015 Aldeburgh Poetry Festival, giving a talk on Shetlandic literature’s relationship with the rest of Europe. Through this I formed connections with the Poetry School and started exploring broader contexts of the relationship between poetry and islands.

A common theme (perhaps a bit like my watery poems in the tea house) began to form. Many commentators were fascinated by the quincentenary of Thomas More’s Utopia, and this became useful as a basis for a more general and theoretical exploration of islands, islandness, poetry and their many connections.

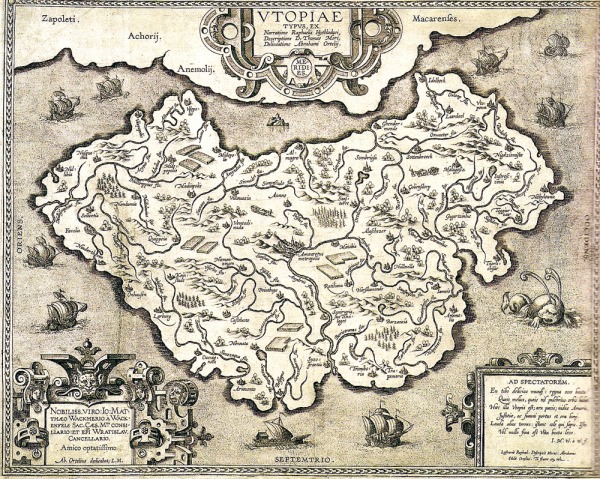

Another map of Utopia

2016 has been a hard for everyone; I think we have all felt the need to escape to both real and imaginary islands at some point this year, a space to contemplate life at a removed distance. So using More’s Utopia as a focus (and haven) for poetry makes sense, and on my upcoming course, Utopia Island Studio, we will do exactly that. Many of the poets and poetries we will study will be produced by islanders like me, and some by islanders more like George MacKay Brown or Lise Sinclair whose physical connection to the landscape, the thoughtscape, the lifescape of being on and of an island that they couldn’t escape, both literally and emotionally. Some are metaphors, like both More’s Utopia and the ‘flip side’ which naturally suggests itself, Alexander Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago. Whilst one is dystopian and non-fictional and the other is an effective satire, both display themes which illuminate on islands and islandness from the minds of writers inhabiting significant landmasses.

Islands pull us back to our origins, but also towards the future. As historian Christopher Hampton has noticed, More conceived of his perfect island as a thought experiment reacting to social and political changes taking place in England that closely echo today, looking backward and forward at the same time:

‘[Utopia] reflects the the conditions of the England More actually lived in and his sense of shock at the ruthlessness with which the new rich men were prepared to sweep aside (or transform to their own great profit) the old-established structures of the agricultural and social system they were in fact displacing … it also sets out to delineate a cooperative system of work and life which repudiates the concept of the inequality of wealth and of condition that governed More’s world’

But it’s worth remembering, Utopia wasn’t an island until the inhabitants agreed to dig a trench, a channel separating them from their near neighbours. For those of us from or on real islands, such measures are unnecessary, and creating and maintaining connections beyond the isles is the thing which takes all the effort. I write at the lively end of a twelve hour boat trip back to ‘civilization’ after catching up with family and friends in Shetland. There is also a real danger, which I’m not sure I always avoid succumbing to, of utopianising an island past. To para-phrase Edwin Muir, who recognised this of his Edenic isle of Wyre – ‘You can’t go back. If you go back, you’ll ruin it’. Utopia literally means ‘no-place’.

An aerial view of the pier in Wyre

So whether you buy John Donne’s diagnosis or you have ideas of your own, whether you’ve never made beyond the near surf of your home or the great sea roads are as a garden path to you, whether you’re a bridge builder or a boat burner, please join me on Utopia Island Studio and let us make sense of the tides we are facing and explore the many rich cultures waiting to welcome the canny traveller. Get your feet wet. The water’s lovely.

Explore real and imagined islands and their literature with Christie Williamson on Utopia Island Studio, a new three week poetry course from the Poetry School. Book online or ring us on 0207 582 1679.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.