I had just turned 18 when I moved out of my childhood home and into an apartment with my boyfriend.

Although I hoped my young relationship would last, there was something in me that said my treasured objects would be safer at home. Built by my grandfather for my grandmother after World War II, it had provided a sturdy roof to three generations. Even though my home wasn’t always a happy one, it was a steadfast place I could always come back to.

Before moving out, I tucked boxes of my journals under my bed, left family heirlooms dusted on my shelves, hung photos of people I loved on my walls. I remember standing in that room, hoping for an act of infusion. Drinking in my whole young life, touching each object individually. Even though I visited rarely after the move, each time I did I walked purposefully back to my room—which was kept as I left it—to submerge myself in the memories that were held there.

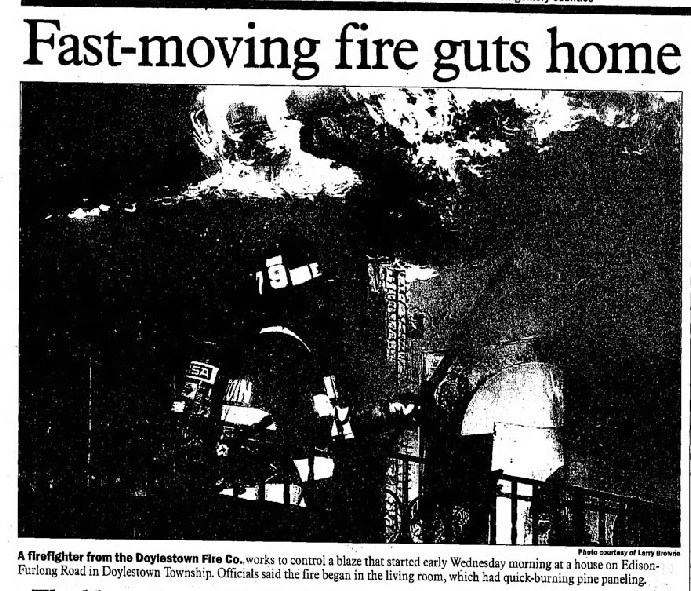

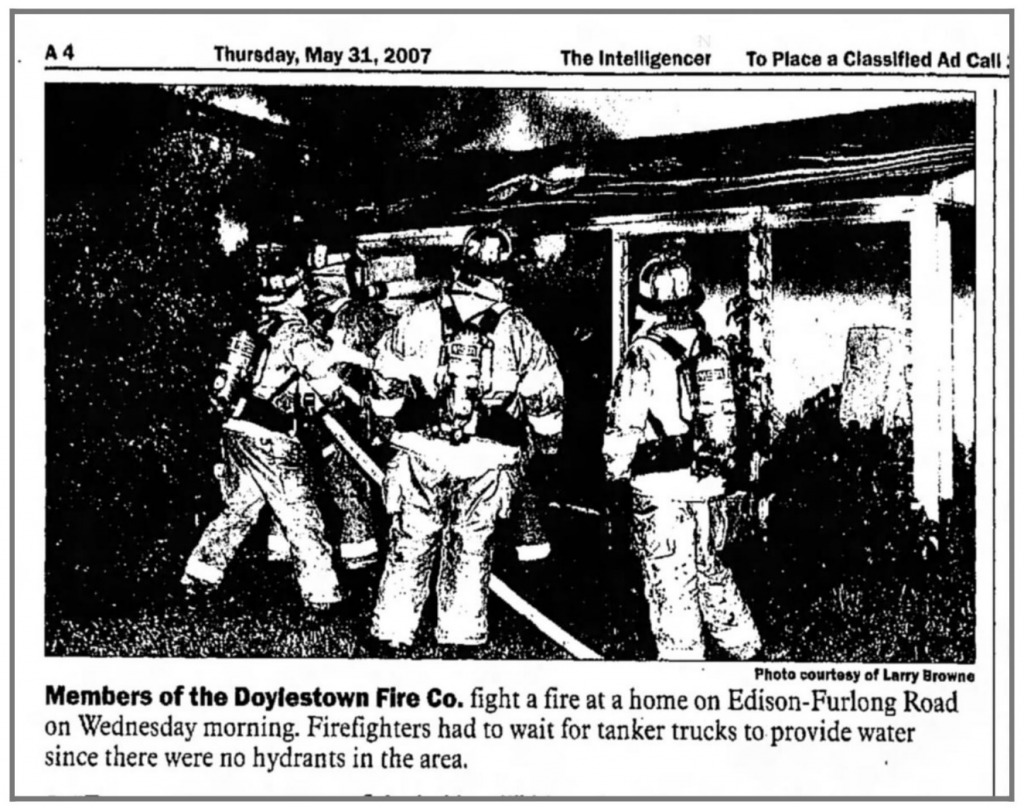

Three years later—to be exact, at 1:07am on May 31st, 2007—the Doylestown Fire Company was dispatched to 464 Edison Furlong Road. Over the radio, police officers reported that flames were erupting from the front of the house and spreading fast. According to the local paper, Ladder 79 and Engine 19 arrived to ‘assist with the tanker shuttle and provide an air cascade’. The end of the article states that there was ‘no entrapment’, that all residents were out of the building. Those residents were my parents and younger brother.

At this point, I was still living with my boyfriend so I wasn’t there to feel the heat, hear the panic, make a narrow escape. However, I heard the cries crackle down the phone as our house burned and remember time slowing down: I couldn’t dress fast enough, drive fast enough. By the time I arrived, everything was gone.

On the day, tall flames surged through the house. Although the living room sofa—near the front door—had been the ignition point the fire quickly made its way to my back bedroom. At the time, our road had no fire hydrants and the engines needed to pump water from a pond a half a mile away. They called tanker trucks full of water in from neighboring counties. It wasn’t enough.

Finally, when the flames were extinguished and everything was left dripping with pond water and wet ash, we were invited to walk towards the back of the house to see if anything was salvageable. My clearest memory was looking up at what was left of my bedroom walls. There I could see the black outline of photographs stretching up like ghosts.

Although I was consumed by loss – the loss of my handwritten journals and personal objects, the loss of my history and home – I wasn’t a survivor in the same way my parents and brother were. I stayed awake for days after wondering what they’d left behind, what they’d lost of themselves—and each other—in the house before it burned to the ground.

I thought of my Mom carrying our terrified German Shepard out onto the lawn. I thought of my brother who admitted that, without his things, he didn’t know who he was. I thought of my Dad who started the fire, accidentally. He was so hurt by it all that he slept for days afterwards, barely talked to anyone.

Since that night, fire has followed me. I often read, write and think about fire. So often, in fact, that it is the subject of my forthcoming poetry collection, How To Carry Fire (Parthian Books, 2020). Days after the house burned down, I remember reading dozens of articles in medical journals. Their matter of fact tone and findings soothed me. The longer the title, the better. I remember printing and saving an article by Keane et al (2000) called ‘A Typology of Residential Fire Survivors’ Multidimensional Needs’. It taught me what survivors carry after fire:

Fire survivors’ stories tell us much about the broad range of fire-related losses experienced, their diverse emotional reactions, and attempts to ascribe meaning to these losses, and relate how the complex sequelae of home fires continue to compromise the multiple dimensions of their lives. Feelings of fear, relief, discouragement, anger, rejection, isolation, frustration, the perception of lost dreams, and even thankfulness are themes found in their vivid comments.

More than ten years on, I still think of our burning home. Every time I sit next to beach bonfires, roast marshmallows, shove kindling into a woodstove, I consider again what fire brings and takes away from us. As a writer, I am fascinated by how fire survivors tell their stories as well as how fire is depicted in mythology (see: Prometheus) and even in our media (see: the fiery metaphors of American politics). But most of all, I am interested in how poets speak to, and about, fire. It is this obsession that has led me to develop an upcoming course on the poetics of fire.

My new online course, Lighting the Flame: Writing Fire Studio will give all those who join a chance to consider how fire enters our lives. We will read poetry which explores the elemental, physical, and metaphorical incarnations of fire. We will write our own inner and outer fires together, speaking to themes so often represented by its flames: destruction, growth and passion. If you have ever sat awed beside a fire, then this course is for you. Come along and learn all the ways in which poetry can burn.

Charge your poems with fire’s many themes on Christina Thatcher’s Lighting the Flame: Writing Fire Studio. Call 0207 582 1679 or book online.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.