So with one bound, Jack was free …

and he woke up to find it had all been a dream.

But when do you wake from the book of the dream,

shrug it off with a cold shower, a shot of black coffee?

There can be no forgetting; even after the fire

the archives are always somewhere intact –

in the world, or that part of the mind that the mind

cannot contemplate …from Don Paterson’s ‘The Alexandrian Library’

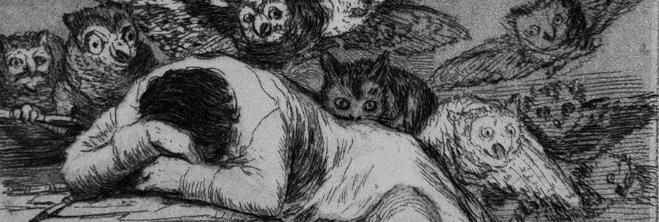

The best poems are places to get excited and surprised, intoxicated and lost, amazed and frightened in. The same goes for dreams. Even before the “person from Porlock” famously interrupted Samuel Taylor Coleridge from composing his reverie of Kubla Khan and his “stately pleasure-dome”, poetry and dreams have had plenty in common.

Both are full of symbolism, where, according to Freudian psychoanalysis, people and objects often represent hidden ideas and emotions, manifestations of our desires and fears. Both draw you in, and tend to affect your thoughts and feelings in ways you can’t control. A dream, like a poem, bridges the divide between our everyday way of looking at the world, and the murky depths of the subconscious. It reveals the extraordinary lurking beneath the familiar.

As it did for Coleridge, dreams can even inspire creativity. How often have you woken from a dream, whether seemingly real or downright strange, with a story you wanted to write down? Or the first line of a new poem? Perhaps you keep a dream diary, and draw on it for inspiration. We are such stuff as dreams are made on, as Shakespeare’s Prospero knew. In dreams begin responsibility, said W B Yeats. Far from being flights of fancy or whimsy, dreams of all kinds might help us understand ourselves, and the world around us, with renewed clarity.

I’ve always been fascinated by dreams – no surprise they’re often a feature, a vehicle, an atmosphere or a landscape in the poems I admire and enjoy the most. Take Michael Donaghy’s ‘My Flu’, where the speaker is suffering time-and-space-shifting hallucinations, fitful between one world and another, unsure what is real and what is dreamed:

I’d swear blind it’s June, 1962.

Oswald’s back from Minsk. U2s glide over Cuba.

My cousin’s in Saigon. My father’s in bed

with my mother. I’m eight and in bed with my flu.

I’d swear, but I can’t be recalling this sharp reek of Vicks,

the bedroom’s fevered wallpaper, the neighbour’s TV,

the rain, the tyres’ hiss through rain, the rain smell.

This would never stand up in court – I’m asleep…

Or how about the somnambulating strangeness of John Burnside’s ‘Animals’, where the dream-world brings a powerful sense of personal revelation, brought back to the apparent land-of-the-living:

Even now, we sometimes wake from dreams

of moving from room to room, with its scent on our handsand a slickness of musk and fur

on our sleep-washed skins,though what I sense in this, and cannot tell

is not the continuity we understandas self, but life …

Or Frances Leviston’s remarkable ‘Incubus’, where memories of a shape-shifting crime continue to haunt the poem’s speaker, leaving her questioning the reality of what has befallen her:

What happens now is I make a confession –

Confess, though I am the victim here,

To having the most incredible dreams

I believed were real, as long as they lasted;

To having had dreams I believed were ended

When the end was only a part of the dream,

The part where you wake in your own bedroom

Glad to be woken, till the door creaks

And whatever it was you were running from

Walks right in. I confess to recurring

Dreams in which my room is haunted

That seem more real than my waking life,

To a ghost who comes in the form of a pressure

Imprisoning me …

In my own writing, dreams have come to preoccupy and shape my poems more and more. Allowing myself the freedom to think, feel and write through the narrative device and concept of the dream, I’ve found that I’ve penned poems that close the gap between the real and the imagined, both in feared and wished-for possible worlds. I’ve ended up exploring the spaces between what happened and what might have, between roads taken and roads not, in ways I could never have expected.

Dreams, then, can be and mean a great many things in poems. Far from flights of fancy or whimsy, they are vital, unnerving, invigorating and powerfully emotive territory for poems to explore. If they fascinate you like they do me, let’s find out how deep down the rabbit-hole your poems will venture, and bring the phantasmagoric alive in your own writing…

Want to suffuse your poems with the power and possibility of the phantasmagorical? Book your place on Ben’s new online course ‘Dream On: Waking Up Your Poems with the Phantasmagoric’ or ring us on 0207 582 1679.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.