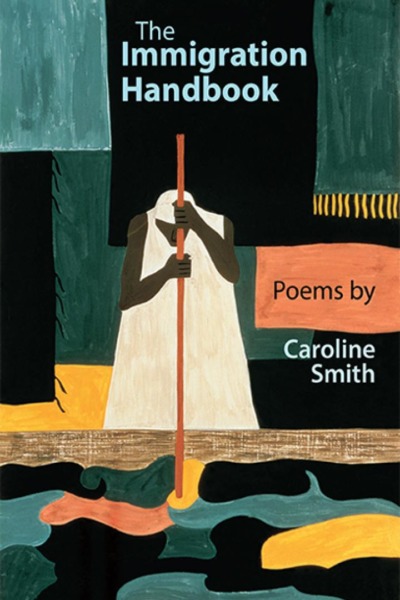

In the fourth instalment of our Ted Hughes Award ‘How I Did It’ series, Caroline Smith explains the creative process behind ‘The Scarlet Lizard’ from her shortlisted work The Immigration Handbook.

Caroline Smith’s The Immigration Handbook is the fruit of her career as an Immigration Caseworker for one of the most diverse inner-city areas in London. Immigrants’ dramatic emotions, circumstances and feelings are conveyed in beautifully clear, expressive language while, amid these human and lyrical moments, the cold language of bureaucrats runs like an icy stream. We also hear from judges, social workers, immigration officers and caseworkers who must enforce – often with brutal detachment, but just as often with reluctance and empathy – the laws of the state. Written over a period of years, these poems are a moving record of global people movement: the story of our time.

For me poetry and art are at the heart of life – a driving force – not a commentary upon it. I did not write The Immigration Handbook to try to change immigration policy, but I knew the climate of the immigration debate needed to change and as an artist I felt compelled to write these poems.

Working as an immigration caseworker for a Member of Parliament, I get the chance to see immigration from a multiplicity of angles and perspectives. In our surgeries I hear first-hand the despair and frustration of people trapped in the system, the victims of rule changes and bureaucratic mistakes, the prey of bogus lawyers. I also speak to the decision makers in the Home Office, the politicians who make the laws. I analyse the judgements and decisions from the Courts and Tribunals. The poems in The Immigration Handbook work together to give a whole picture that reflects this multiplicity of perspectives.

To be asked to focus on one poem, is to look from one angle only so I have chosen ‘The Scarlet Lizard’ because it deals with a theme that is constant throughout the whole collection.

‘The Scarlet Lizard’ is about the importance of language in immigration law and in poetry. How words matter, how they can be critical in determining someone’s fate; whether they will be allowed to stay in this country or be deported to a country in which they fear torture and death. Convincing an immigration judge that a story is true and credible is everything – like Scheherazade, who I have referenced at the front of my book – a persuasive story can mean the difference between life and death.

In an earlier poem ‘Selection’ I concentrate on the opacity of the way the Home Office uses language; their deliberate obfuscation to disguise the true meaning of their words. They will ‘invite’ a failed asylum seeker to a ‘Service Event’: the soft, welcoming word ‘invitation’, the unthreatening activity of ‘service’, disguise a devastating decision to refuse and to detain and to deport. In another poem, ‘Asylum Interview’ I focus on the interviewer deliberately misinterpreting the answers given by the interviewee as to why she has claimed asylum. But I also show the way in which asylum seekers too will speak in set phrases that they have been instructed to use by their lawyers, because these words fit the rules and legal precedents for being granted asylum.

In ‘The Scarlet Lizard’ an immigration judge is dealing with all these layers of meaning; a professional, but in this quiet moment, overwhelmed by the immensity of his task to discern the truth in the scores of cases he must read and judge and decide upon. He is conscious of the enormity of refusing someone and sending them back.

He must be convinced, discern the credible through the layers of stories, both those presented and those concealed. He must weigh up accounts of asylum seekers whose first language is not English, who are afraid of the authorities, who have fled with no documents and are traumatised by the events that have happened to them, such that they cannot easily put them into words.

Like a poet, the immigration judge uses metaphor, the tools of poetry, to discern a flicker of truth in the appelant’s narrative.

‘He longed to see the quick movement of a scarlet lizard weaving unexpectedly through the parched, cracked hexagons of a legal phrase’,

He needs a clinching detail that can bring a story to life, a vivid observation, an unexpected element, an unpredictable turn in the story that doesn’t chart an obvious path to the longed-for outcome. He looks to the power of language to convince and illuminate, to see the authentic within the lawyers’ legal speak used to frame a story within a Geneva Convention reason for a grant of asylum.

It took me about five years to write The Immigration Handbook and I was still including poems up until the day before the proofs were being sent to print, driving my patient editor to distraction! I had however, been thinking about it for many years. The subject is so huge I found it hard to find a way in. I knew I didn’t want to write a polemic, I wanted it to be centred around the impact of the system on the people trapped in it and to create an emotional response in the reader in this way. Like the immigration judge in ‘The Scarlet Lizard’, to see the human beings behind the statistics and legal speak.

I finally found the key to writing The Immigration Handbook through theatre. I happened to see a series of Shakespeare plays. I realised Shakespeare presents whole characters in dramatic tension with difficult decisions to make, in the most extreme and challenging situations. He presents boundary moments in people’s lives, the consequences of action and inaction, actors caught up in the ebb and flow of social currents and the contingencies of fate. But above all he does not judge his characters.

I originally trained as a sculptor and as soon as I began to see the poems as three dimensional and to withdraw myself, as the narrator from the poems, I felt they began to work. I remember when this first happened with one of the poems – I realised I had begun to think as the character, to use metaphors that could be part of the character’s unconscious instead of my commentary on them. I went back to some of my earliest poems and rewrote them from within the character’s own perspective.

Although I don’t write in a conventional form, the structure of a poem is very important to me. My technique was honed by the discipline of writing thousands of letters to the Home Office over the past fifteen years. A turn of phrase, a report, situations of injustice and poignancy would jump out at me in my day to day work and gave me sparks of ideas. These fragments would sit in the background until there was something else to juxtapose against them. Being so immersed in the subject and carrying so many stories and incidents and letters around in my head – a portable and abstract version of my sculpture studio – meant unexpected images would come into my mind naturally because they were already part of my daily life.

In The Immigration Handbook I have no interest in revealing the sensational; to record the horrific stories I hear and read on a daily basis. I wanted to use stripped back language, focus on the subtle and human detail, the different angle, to contrast the official language of a report with a lyrical moment, like the immigration judge – look to the tools of poetry to convince the reader.

The Scarlet Lizard

Nothing moves

except the evening light

crossing the Judge’s room.

The lawyers’ skeleton arguments

lay piled on his desk.

They seemed to him brittle

as bleached poppies,

tapped of their seeds.

He longed to see the quick movement

of a scarlet lizard weaving unexpectedly

through the parched, cracked hexagons

of a legal phrase, to hear the snapped stick

fritter away from a hiding place;

to feel the cold, diaphanous weed grip

in the black current of a border crossing.

He needed to sense some quiver of

indecision, an odd detail

that would open the truth of their words;

chinks of light shining

through shuttered doors.

Find out more information about The Immigration Handbook and buy the book at Seren Books.

Find out more information about The Immigration Handbook and buy the book at Seren Books.

Caroline Smith originally trained as a sculptor at Goldsmith’s College. Her first publication was a 30-page narrative poem ‘Edith’, which was followed by a full collection, The Thistles of the Hesperides in 2000. Published widely in journals like Poetry Wales, Poetry Review, Staple, Orbis and Stand, she has twice won prizes in the Troubadour Poetry Competition. Smith has had work set to music, broadcast on the BBC and is also the author of a musical play, The Bedseller’s Tale. Her latest collection The Immigration Handbook was published by Seren Books in 2016.

We have asked all poets shortlisted for this year’s Ted Hughes Award for New Work in Poetry to tell us about their writing process. For more blogs visit poetryschool.com/how-I-did-it

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.