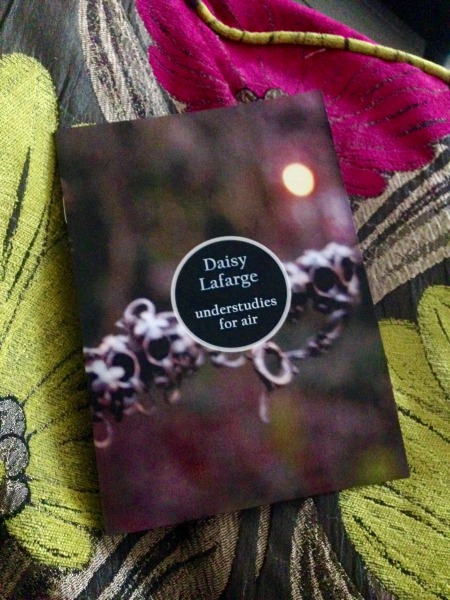

Welcome to the final instalment of our Eric Gregory Award 2017 ‘How I Did It’ series. We asked the winners of this year’s awards to explain the process their award-winning poems. Last up is Daisy Lafarge talking about her pamphlet, understudies for air – published August 2017. The Eric Gregory Awards 2018 will open for entries in September.

understudies for air – a total of 23 poems (or 23 parts of one poem) – came together in all the ways it shouldn’t have. To begin with, I’d been writing nothing but prose and academese for months, and had dramatically, bitterly declared to a close friend that I was ‘done’ with writing poems.

Such crises are entertaining in retrospective but cripplingly believable in their prime; my friend did the right thing by not taking me at all seriously – but letting me think he did. Tip: find a friend like this. While crises take any number of forms – often unrelated (or oblivious) to whatever has prompted them – this particular one had come about with regard to the problem of position and voice. Who did the poem’s voice belong to, if anyone? And by its own speaking, what other voices – histories, subjectivities – did the poem speak over? Was I really sure it was deserving of airtime?

The last poem I wrote before the understudies sequence was a long, fractured preamble to these anxieties. sixteen bells for a white marriage (published in Swimmers pamphlet #4) comprised a lyric loosely addressed to a friend, written in a staccato first person of ‘I, I, I’s, making it snag, stutter and trip on its own terms of expression. The ‘I’s peal awkwardly throughout the poem, and when counted make up the sixteen ‘bells’ of the title.

That had felt like the end. How was I going to find a way around ‘I’ – that I was sick of – but that kept ‘I’s intimacy & urgency? & whose ‘I’ anyway?

Over Christmas I decided to take two weeks off prose. I was staying with my godfather’s family (as their adoptee) on an island & for two weeks the internet was more or less down due to storms. I wasn’t used to the discipline of prose & in stepping back from it I began to get excited about all the things I hadn’t allowed myself to: arguments that don’t add up, words that should be pruned from sentences, nomenclature for its own sake …

Maybe because I thought was ‘over’ writing poetry I didn’t exact the usual censoring & harsh judgement on my note-making: I kept a pad in my pocket at all times & scribbled down words, phrases, concepts – everything felt deliciously vital & relevant. The old anxieties weren’t clamant because I wasn’t – I still don’t know how my superego fell for this – writing ‘poems’.

I moved onto my laptop & the thing that came first was the word understudies. What would an ‘understudy’ poem look like? A poem that is not quite ready to be a poem but might get called to the stage to act like one. Artists make sketches before moving on to the final work, but often sketches are the work; the more I thought about ‘understudy’ poems the more I realised there had to be a whole company of them: sketches towards possible poems.

This notion – that I wasn’t writing poems but something towards poems – took off a significant amount of pressure, & is maybe why I wrote them in a more concentrated period than I have with anything else. I felt less accountable for them, less policing of their voice & position – because I knew these were multiple.

~

Content & subject matter are perhaps harder to gloss – not to mention the dreaded ‘this poem is about …’ that usually sends my attention elsewhere.

What I can do instead is talk around some of the catalysts. I’d long been thinking on and off about air, through a number of mutually distorting lenses: pollution, dystopian (and actual) privatisation of resources, Pre-Socratic philosophy & the ‘porosity’ of infancy: what can be absorbed (or malabsorbed) in the primal, familial ‘air’. Parental weather: stormy or mild. All these things collide in the poem/s that make up understudies.

Pre-Socratic philosophers were obsessed with the idea of a universal ‘substance’ (arche) that accounts for everything in existence, which I (pompously) borrowed as an organising principal. This arche was usually taken to be one of the four elements: Thales believed everything was water; Heraclitus, fire; and Anaximenes, air – which he saw as constituting everything else through processes of ‘thinning’ and ‘thickening’. These philosophers were arguably the first scientists – seeking explanation for the world through natural causes rather than the supernatural.*

‘air’ runs through understudies & escapes from the pinning & naming of it enacted by each title: ‘pyrophoria air’; ‘pestilence air’; ‘nostrum air’; ‘scarification air’ (and so on) – hopefully allowing enough space for the reader’s gauging of air(s). I’d hoped each ‘definition’ remained partial and transitory, but containing its own warped truth – like a child’s magical thinking.

~

Over those two weeks we took daily walks on the bleak, barren beaches. The island’s coasts are mostly sand dunes, skewered with clutches of marram grass. The reeds looked exposed and vulnerable, straggled along the windswept crests of the dunes. But later I read up on the ecology of marram, how the plant itself is responsible for the formation and stabilisation of the dunes: by snaring & binding together sand with their extensive root systems. This dynamic became important to me in writing the poems, as a way to think about form:

desecration air

the dunes migrate inwards, sag

like cellulite from the headland.

in birth, you grew maladaptive

breathing patterns to survive

the air, patterns in which you are now

architecturally invested;

your dealings with the air are more frequent

than ever. brittle waves of grit

clump the windlashed marram

who only avoid the sand’s smothering

by growing, syringe-like

into the air, and in so doing suckle

and cleave the dunes around them.

such a boom and bust modality

raises the question of who

is mother to whom, if your method

of resisting an environment

becomes in turn the order

that generates its form

~

* ‘childhood air’, ‘sibling rivalry air’, ‘sapling air’ and ‘false alarm air’ appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of The Poetry Review

Daisy Lafarge lives in Glasgow. She was awarded an Eric Gregory Award in 2017. Her pamphlet understudies for air is out now, published by Sad Press.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.