This year we’ve once again asked the poets shortlisted for the Ted Hughes Award to explain the creative process behind their award-nominated work as part of our ongoing ‘How I Did It‘ series.

In this second instalment, Matthew Francis discusses the writing of The Mabinogi (Faber and Faber), a poetic adaptation of the 14th Century Welsh epic tale sequence.

In January 2014, I went to see my editor, Matthew Hollis of Faber and Faber, and told him I was out of ideas. I had been trying to write lyric poems, and they weren’t working. I knew from experience that long narrative poems, especially those adapted from existing material, worked well for me creatively; I enjoyed the feeling of getting up in the morning knowing exactly what I had to write today. What I needed, I told him, was a project, but I couldn’t think of one. Did he have any suggestions? Rather to my surprise, he had an idea ready: had I ever thought of a poetic adaptation of The Mabinogion?

The Mabinogion is a set of eleven prose tales of magic and adventure, war and romance, originally written in Welsh in the fourteenth century. I had read it on first coming to live in Wales in 1999, and knew how important the book was in the history and culture of my adopted country. It was a daunting task for an incomer, especially one who didn’t speak Welsh. The tales had already inspired many adaptations, including Evangeline Walton’s fantasy tetralogy The Mabinogion, Alan Garner’s YA classic The Owl Service and the recent series of novellas New Stories from the Mabinogion, written by distinguished Welsh writers and published by Seren Press. But these were all in prose; the idea of a book-length poetic adaptation was new and exciting. Rereading the tales, it seemed to me that their magic and strangeness would work particularly well in poetry.

My first idea was to adapt all eleven tales. After a few weeks it became clear that this would produce an unwieldy book, and I decided to restrict myself to the first four stories, the ones which describe themselves as The Four Branches of the Mabinogi. (Mabinogion, not really a Welsh word and used in error by early translators, is now reserved for the book as a whole.) These are arguably the most fascinating of the set, and tell a more or less continuous story, though one with many twists and turns. So my sequence would have four sections, or branches. It would need to be broken up further, as long poems make a lot of demands on the reader, who is usually grateful to be given plenty of places to rest. From the start, I had a picture in my mind of what the text would look like on the page.

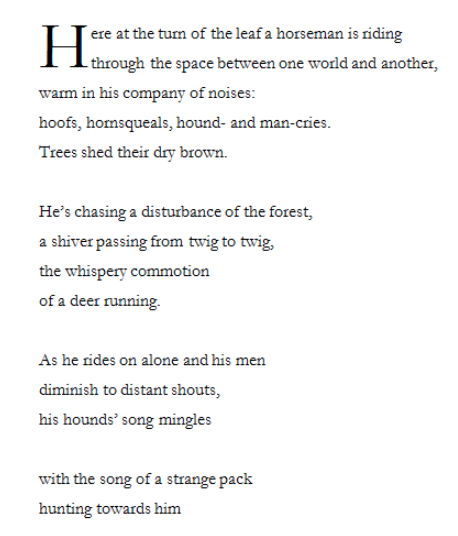

The lines would be syllabic – that is, they would have a fixed number of syllables, regardless of stress-patterns. I have used this form a lot over the years, and have become especially fond of stanzas where the syllable count dimishes, line by line, This gives them an attractive appearance, and also forces me to write more economically as the stanza advances, intensifying the language and making for an interesting technical challenge. I decided to make the stanza lengths diminish, too: five lines, then four, then three, then two. That adds up to fourteen – the same length as a sonnet. Then I would insert a larger space and begin the next ‘sonnet’, with no numbering or title. The result, I thought, would look a bit like a medieval manuscript with bits of the text missing due to age. That gave me the idea of marking new subsections within each branch by the use of a large ‘dropped’ capital letter, sometimes used to begin a chapter in old books – the effect would be similar to that of a medieval illuminated capital. Aware that readers might have trouble following the story, I came up with the solution of marginal notes in italics, like the ones Coleridge used for ‘The Rime of the Ancient Mariner’. This saved me from trying to cram too much detail into the text itself.

The First Branch of The Mabinogi begins with a man hunting in a forest. He is Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed, and he is shortly to meet the King of the magical realm of Annwfn (which I translate as Unland). It is an encounter which will change his life and set off a series of fantastic events extending through all four branches. So my poetic version begins with a hunting scene: I pictured the forest in autumn, when the leaves have turned and are beginning to fall – and that gave me my first line, as I realized that ‘the turn of the leaf’ was a potential pun. Like the turning season, Pwyll has unwittingly reached a turning point in his life, and the reader, having just turned the leaf of the page, is about to embark on new adventures with him.

You can find out more about The Mabinogi from Faber and Faber here.

You can find out more about The Mabinogi from Faber and Faber here.

Matthew Francis is the author of The Mabinogi and four previous collections with Faber, most recently Muscovy (2013). He has twice been shortlisted for the Forward Prize, and in 2004 was chosen as one of the Next Generation poets. He has also edited W. S. Graham’s New Collected Poems, and published a collection of short stories and two novels, the second of which, The Book of the Needle (Cinnamon Press), came out in 2014. Matthew Francis lives in West Wales and is Professor in Creative Writing at Aberystwyth University.

We asked all the poets shortlisted for the Poetry Society’s Ted Hughes Award for New Work in Poetry to tell us about their writing process. For more blogs visit poetryschool.com/how-I-did-it

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.