This year we’ve once again asked the poets shortlisted for the Ted Hughes Award to explain the creative process behind their award-nominated work as part of our ongoing ‘How I Did It‘ series.

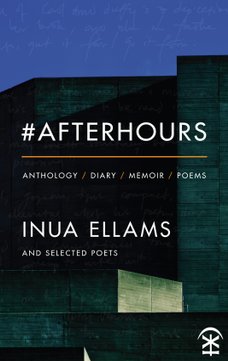

In this final instalment, Inua Ellams discusses #Afterhours, a collection comprising response poems, memoir, diary and artwork.

In 2014 I turned 30 and wished to mark it with a project about the end of childhood by writing response-poems to the work of British and Irish poets. I think, arguably, all poems are response poems and attempts by the poet to find or claim personal space in any given topic.

I looked for poems published between 1984 and 2002, from when I was born to when I turned 18, and in writing, I stayed stay as close as possible to aspects of the originals – subject matter, structure, syntax, length etc – but I reset them. I culturally transposed/translated the poems, took them from Britain and Ireland and set in the Nigeria, Ireland and England of my childhood.

Rather than taking say a floorboard from a house and using it as a starting point to make a new house, or making a house of a similar hue or aesthetic, I rebuilt each poem by using my past experiences and although the work would ever have a close relationship with the originals, I wanted them to very much exist outside of each other’s space.

I believe a response poem has to stand up on its own. One of my pet peeves in poetry is work that references obscure texts, paintings, music etc… it can alienate a reader, make one feel inadequate, less than, poorly educated and embarrassed. For me, poetry should always include more than exclude, should welcome-as-you-are more than question-your-preparedness. If the response poem relies too heavily on the first text, or require the reader to source and find the original poem in order to understand, then it fails. A poem should be a world onto itself, a floating island, a house in a vacuum.

Language is ever-changing and the poets of any given generation determine the relevance of those who wrote before them. By recasting old words and texts in contemporary voices or languages, we frame them, give them relevance or strip them of their gravitas. It can be an inexpensive and in-exhaustive act of defiance.

Sometimes, the simple act of reading a poem is a way of reclamation. I never forget that Rudyard Kipling who wrote ‘If’ also wrote ‘The White Man’s Burden’ where he described people of colour, those colonised, as ‘half-devil and half-child’. When he concludes in ‘If’ “you’ll be a Man, my son!” – it is clear that I am not considered a man in his eyes. This, for me, makes Serena Williams’ (whose femininity and blackness has been questioned and ridiculed for so long) reading of his poem, incredibly subversive, political and powerful:

In that last line, where she says/rewrites ‘Woman, Sister’ – not only does she emasculate the poem, and in that, Kipling, she uses it to empower women of colour (“sister”), those who suffered the most under the foreign policy of colonisation.

Most of my response-poems do not have political aspirations. The first few are family, reincarnation, spirituality, mythology, markets and shopping. The fourth is about my parents meeting and is a response to this by Seamus Heaney.

A Shooting Script 1987

#After Seamus Heaney

Book: The Haw Lantern

They are riding from what might have been

towards what will come to be, in a locked shot:

Missionaries on bicycles greeting Muslim boys,

priming the eighties for the troubled future,

still pedalling out at the end of the lens,

circling the teens like ambushed prey.

Mix to desert dust floating in hot breeze.

An ominous long sequence. Pan and fade.

Then voices over, of different tribal dogma,

discussing politics, failed civilian rule, the pull

of Christian capital, dwindling grazing land,

occurrence of names like Matthew and Paul.

A close-up on the cat’s eye of a white button

pulling back wide to a kaftan, black turban,

rifle, parched fields, herd of starving cattle.

Freeze his livid face. Let the credits run.

And just when it looks as if it is all over –

tracking shots of a mosque, the muezzin stands

for the call to prayer, sings over the young

interfaith couple washing off their hands.

You can buy #Afterhours from Nine Arches Press here.

You can buy #Afterhours from Nine Arches Press here.

Born in Nigeria, Inua Ellams is an award winning poet, playwright & founder of the Midnight Run. Identity, Displacement & Destiny are reoccurring themes in his work in which he tries mixing the old with the new, the traditional with the contemporary. He has three pamphlets of poetry published by Flipped Eye, Akashic and several plays by Oberon. He won an Edinburgh Fringe First award for The 14th Tale, and The Live Canon Prize for Shame Is The Cape I wear. He has been published in The Poetry Review Summer 2016, Best British Poetry (Salt) 2015, The Salt Book of Younger Poets 2012, Chorus (MTV Books), City State (Penned in the Margins) TEN The New Wave (Bloodaxe), and in magazines such as Poetry Paper, Magma, Pen International, Wasafiri and Oxford Poetry.

We asked the poets shortlisted for the Poetry Society’s Ted Hughes Award for New Work in Poetry to tell us about their writing process. For more blogs visit poetryschool.com/how-I-did-it

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.