This year we’ve once again asked the poets shortlisted for the Ted Hughes Award to explain the creative process behind their award-nominated work as part of our ongoing ‘How I Did It‘ series.

In this third instalment, Antony Owen talks about writing The Nagasaki Elder (V. Press), a journey through the bombed cities of Japan, drawing on accounts of survivors.

For me, every poem is sensory and, if it is not felt by the writer, then it will not be felt by the reader.

The Nagasaki Elder began in 1984, when I was 11 years old. In 1984, the Cold War was at a record peak and the handful of super-powers, including Britain, collectively had over 50,000 nuclear warheads. (This is three times the number of nuclear warheads that we have in our possession today.) Back then, art and music spoke out against nuclear proliferation, from Frankie Goes to Hollywood’s ‘Two Tribes’ to Panorama documentaries about what would happen if a nuclear war took place in Britain. We only had four TV stations and no internet, so the influence was concentrated and very effective.

One day, as part of our school Humanities class, we watched Threads – a docu-drama produced by BBC and written by the hugely unsung writer Barry Hines, who also wrote A Kestrel for a Knave (AKA Kes). Threads was a visceral drama about the political algorithms, reminiscent of today, that lead to a nuclear stand-off and then all-out conflict. In Threads, a one-megaton (one million ton TNT equivalent) nuclear bomb explodes above Sheffield, which was an industrial city. I strongly identified with this, growing up in Coventry on the same lane where Jaguar cars were made. To put it into perspective, a one-megaton bomb is approximately 60 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped above Hiroshima. These people depicted in Threads were my kin, working class people I identified with, and it struck me very hard.

One scene stayed with me, which was a young couple nesting. The woman protagonist was pregnant, scraping away wallpaper and decorating a house with her lover. In the background was radio coverage of an escalating conflict between East and West and she just broke down crying as the “Threads” of civilised society unravelled. This scene unknowingly was the seed of The Nagasaki Elder and it was felt as a young boy, way before I had the capability of articulating those innocent emotions through the very adult poems featured in The Nagasaki Elder.

Once my interest was stimulated by Threads, I had a thirst for knowledge and learnt about the atomic devastation of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. This fuelled my lifelong interest into the consequences of conflict upon civilians and soldiers (who are also reintegrated civilians with PTSD). In 2014, I met a man called John Hartley who was stationed in Hiroshima in the early 1950s and he introduced me to a peace group in Hiroshima who subsequently got to know my work and invited me over there. I self-funded my trip to Hiroshima as I felt propaganda in WW1 and WW2 had used art to serve the ideals of war mongers, which is something I feel art should never do.

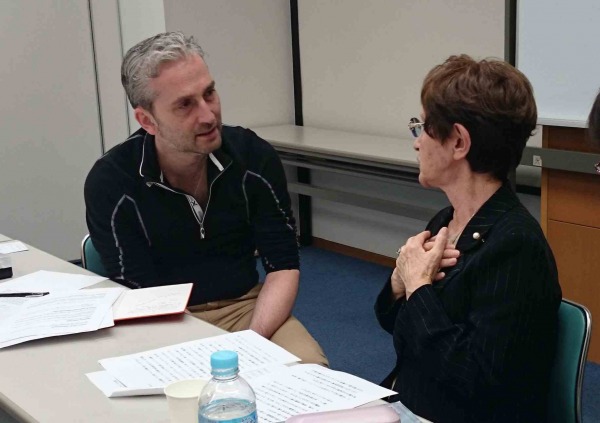

In Hiroshima, I visited many schools and heard testimonies of two atomic bomb survivors known as Hibakusha. One of the survivors spoke to me for approximately 90 minutes and broke down several times as she recounted the events from the calm of the night before the bomb, the awful day itself and her life that followed. I knew I could write about it but that it would be a dangerous book for me to write. However, these survivors were dying out and desperate to pass their stories on to the next generation because they are so important. I wanted stories and poems, so made sure I conducted a narrative structure within the poems. I felt people had to feel that these were fellow human beings to connect with on an emotional level and not a coldly statistical one. Poetry is the conductor to transmit such emotions. I wanted to state the horror of their deaths but also the beauty of those lives.

When writing peace poetry, it is important to balance acts of inhumanity with acts of humanity and strength. The Hibakusha were poems, they had poetry in them in every sense. I just had to capture something that was willing to be captured, so that their message could be free, unlocked through poetry. I also wanted some of the poems and stanzas to be structured like a musical composition, so that the book had the brevity of a poem but the epic feel of short films with music. In many films, we respond emotionally because the musical score or cinematography influence our responses. To me, writing The Nagasaki Elder was to bring a sometimes overlooked Eastern tragedy to the consciousness of Westerners from the perception of a Westerner but with the view of a world citizen, a humanist voyeur stating the events using poetry. Many Japanese poets and film-makers like Akira Kurosawa helped influence the inertia of the poems and compilation. Inertia is an important word, the streetcars in Hiroshima moved on inertia after the bombing, with the carbonised remains of the passengers travelling into the after-life. Art has to continue that movement to be a movement for war and peace poetry.

I wrote most of The Nagasaki Elder during and after my trip, and took many notes when I was over there. I then distilled and refined those images but importantly did not edit the feeling from them. I am an auto-didact but instinctively feel that a good poem must have technical allegiance and discipline yet also must be written with clear and controlled emotions. Imagine one of my idols, Jackson Pollock, shaking as he holds a paintbrush trying to capture a hairline bone; he wouldn’t be able to do it if he was angry, so must await the art in him to paint. This is the same for poetry, the blank page is a world that has to be transferred from the mind of an artist to the beholder’s eye of a reader. If they don’t feel the poem they won’t read it. A poem is a painting of colours we’ve never felt or seen before. We may imagine them as familiar but art is a new world and, if it isn’t, then we have not been transported.

The Nagasaki Elder was a choice, this is how it was written and then the abseil descent into darkness to shed light on to the horrors of nuclear weapons we all want to look away from. Looking away blinds us as much as the nuclear flash. Poets must respond in the same way Douglas, Bain, Scannell, Sitwell did in WW2 when the papers of the day asked, “Where are all our war poets?” War poetry has evolved since then and I want to champion peace poetry in this age of the civilian and refugee. I want to ask on behalf of the voiceless, “Where are all our peace poets?”

Where are you? Join me at the edge!

Purple chalk

Years after the bomb startled water,

koi engulfed the egg-flecked banks,

spawning shockwaves of life.

Years after the ill star was born,

shy women revealed themselves

to men who took their blood and husbands.

Months after the first silent births,

a mother took her unnamed life

and then her soul in a whispering rill.

Weeks after, this girl with the handprint face

explained she was counting to ten, then a flash

printed hide and seek on her face.

Days after, a boy wrote his name in purple chalk –

his yo-yoing eyes spilled across his frame;

they washed his feet before he died.

Before he died, he asked why me?

The boy on the human bonfire

gulped, koi-mouthed, at the sky.

You can find our more about The Nagasaki Elder from V. Press here.

You can find our more about The Nagasaki Elder from V. Press here.

Antony Owen is the author of five poetry collections. His most recent book The Nagasaki Elder was inspired by atomic bomb survivors’ accounts and growing up in Cold War Britain at the peak of nuclear proliferation. His poems have been translated into Japanese, Mandarin and Dutch. CND Peace Education (UK) selected Owen as one of their first national patrons in 2015, and his poems feature in a national CND peace education resource to schools. Owen is also a recipient of the 2016 Coventry Peace & Reconciliation Award for various peace projects.

We asked all the poets shortlisted for the Poetry Society’s Ted Hughes Award for New Work in Poetry to tell us about their writing process. For more blogs visit poetryschool.com/how-I-did-it

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.