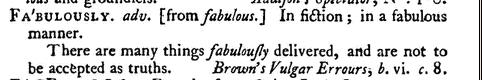

One of the little squabbles I tend to have with the dictionary, is over the word Fable and its family. Although conceding that the fable has at its heart a moral, peppered through Dr Johnson’s definitions is a great suspicion of the telling. A fable is a lye and the writing of a fable is To feign; to not write truth, but fiction.

In Webster’s Dictionary, the definitions of fable are more obviously conflicted. A ‘Fable’ is both: A story or statement that is not true – and also: A narration intended to enforce a useful truth. So, in the lie, lies a truth. At this point Emily Dickinson will always appear on cue in my head:

Tell all the Truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surpriseAs Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

This poem is about using metaphor as a way of reaching a truth, and the fable works in part, as a metaphor. The word metaphor comes from the Greek metaphora, which means to carry over. Traditionally the fable is a method of carrying over a moral and was a staple of school assemblies as I was growing up. I was always a little bored by the tagged-on, point-blank moral of Aesop’s stories and tended to enjoy more the mode of telling and how that appeals to the imagination. I think what fables and parables also teach is how to think in pictures, and how to tell the truth, but slanted.

A TRUTH ALL PACKAGED UP IN A LYE

Poets, as everybody knows, are champion liars . . . God forbid poets ever stop lying. How else can one make up good stories? What I’m talking about is imagination. It’s that faculty that puts us in the shoes of other human beings. There’s no truth without the imagination – Charles Simic

Some truths might be: I failed my driving test; it’s my birthday; I lost my handbag. While these all may not be entirely blinding, upon hearing them, one might say ‘I’m sorry to hear that’ ‘Happy Birthday’ ‘Oh dear.’ The responses one elicits with straightforward facts of this kind are cul-de-sac, blind-alley responses, and might suffice in everyday life, but they are not the kind of things you’d like a reader to say in response to a poem you’ve spent days making.

People who read poems and stories are not interested simply in facts – for this you can write them a shopping list or instructions on how to use the washing machine or tell them that you are a bit fed up with your Internet service provider. Scientifically, when a person is told a series of bland facts, only the language processing parts of the brain light up, as they decode the words into meaning. If you tell them a story involving lots of sensory and physical events, both their sensory and physical cortexes light up, as if they are actually experiencing the events themselves. Incidentally, this is how clichés become clichés – if you hear phrases again and again, they become just words because they no longer stimulate the sensory cortex. It’s the same as crying Wolf, to quote that fable. Hear the word wolf too many times (say it to yourself 20 times now); you disassociate it from a slavering beastie who has come from the forest to gobble up your children.

As a person who reads poems and stories, I want a little slantedness – for the dance of it. The Russian Formalists of the early 20th Century suggested that the distancing or estrangement of an object creates a heightening of our perceptions and stimulates our senses, thus exciting in us an artistic, rather than everyday experience. It’s a similar kind of slowing-down with the fable. If you wanted just the point of the thing, you’d cut to the moral at the end and ignore the story and, basically, the fun.

FABRICATIONS

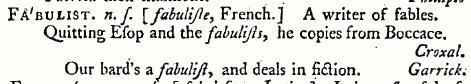

The Ancient Greeks had no real concept of the creative imagination and called whatever a poet made, a fabrication. The word fabrication belongs to the same family as the fabulist, the fable and indeed eventually, the fib (from fibble-fable.) Aristotle praises Homer for having taught poets ‘to lie properly’ in his Poetics. As far as Aristotle was concerned, poetry was a ‘mimesis’ or ‘imitation’ – a rendering of nature, not the thing itself. Can it be said then, that every work of art in every medium is a lye constructed by a fabulist? Perhaps, in the etymological sense, but there are works that claim a closer kinship to the fable than others.

Fables come from the oral tradition, and as such have the folk-tale draped loosely about them. In fables, animals talk and behave in a human way, mythical happenings happen. They are containers for extraordinary events. They are entertaining but didactic. They are tall tales but they are not smoke and mirrors because they never mislead, only illustrate in a slanted manner. Exactly like a metaphor. Once you know how fables work, there is a certain amount of expectation built in to how you read and interpret them.

Take this famous fable about deception – The Wolf in Sheep’s Clothing. As this fable comes from the oral tradition, different slants have been put on it over time. This version is thought to have been the first concerning a wolf disguising itself as a sheep and comes from the 12th century Greek rhetorician Nikephoros Basilakis. It may be different to the version you are familiar with; the preface to this fable is “You will get into trouble if you wear a disguise”. We are reminded here of the fate of the Wolf in Little Red Riding Hood, another folk tale:

A wolf once decided to change his nature by changing his appearance, and thus get plenty to eat. He put on a sheepskin and accompanied the flock to the pasture. The shepherd was fooled by the disguise. When night fell, the shepherd shut up the wolf in the fold with the rest of the sheep and as the fence was placed across the entrance, the sheepfold was securely closed off. But when the shepherd wanted a sheep for his supper, he took his knife and killed the wolf.

And now compare it to this Russell Edson poem, from his 1973 collection, Clam Theater:

The Difficulty with the Tree

A woman was fighting a tree. The tree had come to rage at the woman’s attack, breaking free from its earth it waddled at her with its great root feet.

Goddamn these sentiencies, roared the tree with birds shrieking in its branches.

Look out, you’ll fall on me, you bastard, screamed the woman as she hit at the tree.

The tree whisked and whisked with its leafy branches.

The woman kicked and bit screaming, kill me kill me or I’ll kill you!Her husband seeing the commotion came running crying, what tree has lost patience?

The ax the ax, damnfool, the ax, she screamed.

Oh no, roared the tree dragging its long roots rhythmically limping like a sea lion towards her husband.

But oughtn’t we to talk about this? cried her husband.

But oughtn’t we to talk about this, mimicked his wife.

But what is this all about? he cried.

When you see me killing something you should reason that it will want to kill me back, she screamed.But before her husband could decide what next action to perform the tree had killed both the wife and her husband.

Before the woman died she screamed, now do you see?

He said, what…? And then he died.

There is a certain similarity in tone and voice – a plain, matter-or-fact telling of extraordinary events. Both tales are a little horrific, especially if you side with the Wolf or the husband and wife. The shepherd is only behaving as a shepherd might, the tree is only behaving in the way a tree might if it could. The moral to Edson’s fable might be: Don’t mess with nature, or He who procrastinates is lost, or You can drive out nature with a pitchfork, but she keeps on coming back (Horace). What I have learned here is to always be true to my own nature and to not underestimate Nature.

THE FABLE AND THE PROSE POEM

The brevity and autonomy of the fable have, of late, shepherded the form into the modernist category of poetry: the prose poem. Russell Edson has been described as the American godfather of the prose poem. ‘My ideal prose poem is a small, complete work, utterly logical within its own madness,’ he said in an interview.

The prose poem form is exactly as it says, a hybrid of prose and poetry. On the page it looks like prose and thus carries with it the expectations of cause-and-effect logic. The poetry in the prose poem comes with the greater emphasis on simile, metaphor and symbol. And because they are relatively short, like any other poem might, the prose poem can open up like a Matryoshka – the fewer words and images there are, the more meaning they take on as we engage with them as readers.

The main difference between a fable and a fable-like prose poem is in its presentation. If the text you are about to read features a pre-amble, or carries a moral, it’s very likely going to be a fable. A prose-poem will just sit there and ask you to engage with it and draw your own inferences.

BECOMING A FABULIST

Many people find that writing about personal material is just too exposing. One method of tackling this is to take it so far into the fabulous, so as to make something appear as fiction, so that nobody would recognize the ‘I’ as being you.

Toon Tellegen is very tricksy in his Preface to Raptors:

Years ago I invented someone whom I called my father . . . and in his turn, invented my mother, my brothers and myself. He even, that very same morning, invented the life we should lead.

The poems in the collection all begin with ‘my father’, and although Tellegen has said in interview that the family that he writes about is not his real family, this does seem the ultimate form of liberation; say it is fiction; say it is made up; write a few truths.

My father

twisted the factsand the facts began to tear one by one,

my mother no longer existed,

my brothers woke upmy father took them fishing

and everything he was, he was not

and never would be again,

my brothers glistened,

gasped for airthen my father went on a journey,

my brothers helped him into his golden wings,

lifted him up and threw him into the airand for a split second he was the sun, my sun,

that disappeared behind a cloud.

In all of the poems in Raptors, the father is a mercurial force. He appears and disappears, and constantly his family – as well as the narrator – appear as bit part players in the dramas he creates. But then, according to the preface, Tellegen invented the father, so perhaps it is Tellegen who is responsible after all. . .

When it came to writing the poems in Waiting for Bluebeard, I did a few things with my narrative I. For one, I shifted myself into a she to express the out-of-body type experience you can have when you look back on your life and wonder where you were in it. Another thing I did was moved the story which was in real life set at first in a council house in Luton, and then in a remote farm in the Norfolk countryside, into an otherworldly place. For me this seemed a totally logical thing to do – I was aiming at showing and exploring truths, not delivering facts.

I want to finish with this poem – a fabrication of lyes. Facts are: my parents argued, or didn’t talk; we had cats and kittens; my mother is very good at sewing. This is how it felt some evenings.

The Family at Night

We were rag-dolls after school

and passed long winter evenings like this:

father in his armchair with an unlit pipe,

mother in the kitchen pretending to eat,

my sister and I with our small occupations.We saw little with our button eyes

and spoke even less with our stitched up mouths.

We played at playing till it was time for bed

when mother sewed our eyelids down

so we could get a good night’s rest.We always woke as our human selves

to find the downstairs rooms had altered too.

A chair unstuffed, a table’s legs all wrong,

and, that one time, kittens gone from their basket;

the mother’s bone-hollow meow.

Prose Poets is a new series of short prose essays on poetics by poets. Each essay uses a word and definition excerpt from Samuel Johnson’s first edition of the English Dictionary as a spur towards an exploration of poetry, language and literary criticism, combining a casual, subjective treatment of the chosen theme with personal anecdotes and reflections.

What a fascintating essay – I was tempted to say ‘fabulous’ which is a word I overuse. 😉

Thanks for sharing it, Helen.

Fascinating not fascintating. I haven’t had my first strong coffee of the day yet.

Thanks for the slanted dance of this, Helen. I agree there are quite enough facts in life and part of the joy of poetry is the truth in the ‘lyes’.

Thank you both! 🙂 x

Great essay, Helen – really enjoyed this, and coming back to your poem, even more so.

Thank you so much Di!

This is, er, fabulous, Helen. 😀 What a wonderful tool for writing poetry, prose, lifewriting – everything! I’d love to use it with my students (and myself, obviously): would that be okay?

Hi Morgaine – thank you!

Yes, of course – feel very free to use it for your students. Thank you again 🙂

I always enjoy a thought provoking essay but, at the end I did not want to like the poem as I have an aversion to life writing. However, I loved it. A Gothic Coraline feel with button eyes and and an unseen night world left bare in the morning without explanation. Thank you for un-stitching my eyes.

Hi Val – I agree about ‘life writing’ – I never did it till my fourth book, by which time I couldn’t stop doing it! I suppose it’s all about finding a way in and a method of working that makes it life, but at a slant. That’s how it was for me, anyway. Matthew Sweeney calls this an ‘alternative reality’ rather than Magic Realism. The otherworld is just through the back of the wardrobe, or at the other side of the Ouija Board . . .

Thank you very much for your comments and I am so pleased you liked the poem in the end. I was a bit annoyed when I saw the film Coraline as I’d already written this poem! I then went on to read the book and it’s very chilling!

Thank you for all the insights and distinctions here. This has helped me find focus— in my mind so far, not yet on page—for the kind of writing I like to do but which hadn’t seemed quite right yet. I love your poem, how the images tell the story and the meaning comes without telling it.