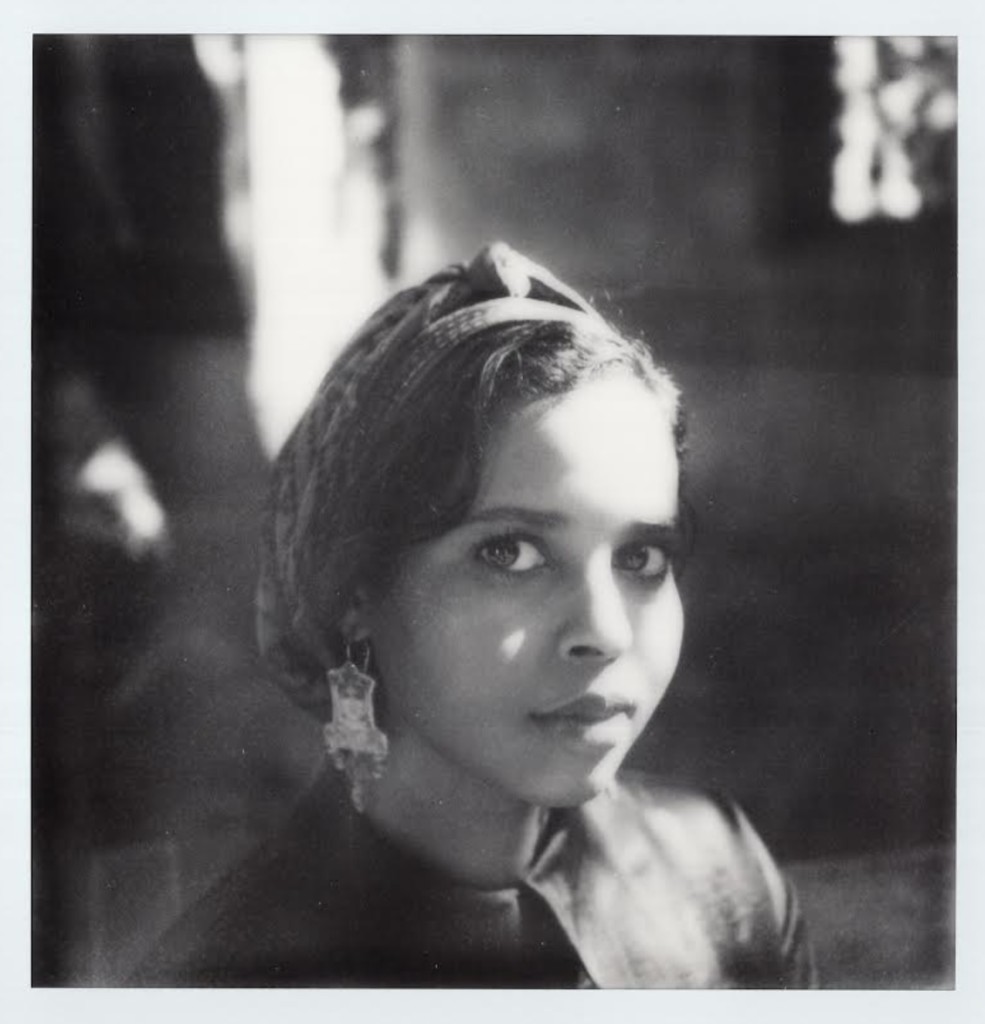

Welcome to our Forward Prizes 2023 ‘How I Did It’ series. This year we asked the poets shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best First Collection to write about the inspiration behind their collection. Here’s Momtaza Mehri on what inspired her to write Bad Diaspora Poems.

This was one of a series of poems I wrote in Nabeul, a coastal town surrounded by the Mediterranean Sea. I was living in Tunis at the time, and I would often drive down to Nabeul with friends. Occasionally, I would take the bus there alone. A strait’s throw away from Sicily, Nabeul is a city of fragrant orange trees and quiet charm, an ideal setting for anyone considering the insecurity of frontiers. I note the setting because of how much it intensified my own state of hesitancy, as well as the tussle between received wisdoms and hard-earned revelations that can define intergenerational experiences of displacement. The facts may not be yours to probe, but you live in the aftermath of inherited fictions. In this sense, this is a restless poem from a restless collection. Irresolution is a difficult position to write from, though it’s the only one that makes sense to me.

Water, or being close to it, always unsettles my writing practice. There’s a grogginess to editing a poem after a swim. Your words feel curiously foreign, as if they were written by someone else, someone more assured in their convictions. In his beautiful, obsessive work of cultural history Haunts of the Black Masseur, Charles Sprawson likened the ‘trance-like condition’ of the swimmer to the opium addicts of the nineteenth century, caught in ‘the feeling of blissful buoyancy, the extension of time, contrasts of temperature, the bliss of the outcast.’ Sprawson was a devoted swimmer, but in this state of chosen suspension, he also saw the poet, another slippery figure. Water emboldens the melancholic. It encourages the brooder. There’s something deliciously emo about writing within sight of a lapping tide.

The poem is concerned with disintegration and reconstitution, the rhythms of falling apart and coming together elsewhere. I was struggling with the idea of community as a kind of engulfment. A gloved hand around the soul. I was thinking about what it means to belong to a family, a people, a poetic tradition, a coastline. Woundedness is the worst adhesive. At times, it feels like that’s the only thing binding us together. We are encouraged to explore our suffering more enthusiastically than our desires. I was attempting to confront these unifying desires. Nationalisms and national patriarchs also interested me. Then there are the poets, prisoners, refugees, and white-robed nomads. Characters who fluidly pass between borders, occupying different, and sometimes overlapping, roles in the construction of national identity.

Think of Beckett warning against the danger ‘in the neatness of identifications’. The poem’s list structure scaffolds this movement from certitude to fragmentation. A kind of descent. The image of a child learning Somali, cradled in the lap of a woman, is invoked alongside English orientalist and Victorian-era explorer Richard Francis Burton, learning the language in much the same way. Poetry helps me think through the monstrosity of alikeness, without the burden of verisimilitude.

Fidel Castro. Siad Barre. George Jackson. 1971. The year the Supreme Revolutionary Council set up a language commission to finalise a national grammar and standard orthography for the Somali language. The same year George Jackson was killed in San Quentin during an escape attempt. Histories converge, as do thwarted dreams of expansion and insurrection. I was grasping at the churns of the 20th century, its reverberating disasters and our shattered beliefs. Balwo, a musical and poetic style pioneered by the Somali musician Abdi Sinimo, was useful here. Elegiac in spirit, balwo takes its name from the word for ‘catastrophe’. In this genre, love and catastrophe are bedfellows.

‘We’ is a word that reoccurs four times in this poem. As I write elsewhere in the collection, the plural personal is the evidence of murderous affinity. Someone is always betrayed by every assumed we.

A Few Facts We Hesitantly Know to Be Somewhat True

I. I am uneasy thinking that you may be attracted to the tragedy of me George Jackson wrote & he could have easily been talking about lovers or prisoners or poets or refugees or all at once or none at all. All deserve love letters.

II. We are one people of one stock of one language of one religion of one coast of one desire.

III. Whatever helps you sleep at night won’t let you rest by day.

IV. Richard Burton learnt Somali in the laps of women. In this way, we are monstrously alike.

V. Equilibrium is not a destination you can relocate to.

VI. Castro and Barre met in 1977. A private encounter with no witnesses. Some say Barre pointed to the map and said that anywhere one of us stood was ours, all ours. We just had to take it.

VII. Our proverbs are often defence mechanisms.

VIII. You can’t call us Horners and seriously expect us not to be hard-headed.

IX. Art is something we do when the war ends.

X. Even when no one does on the journey, something always does.

Momtaza Mehri is a poet and independent researcher working across criticism, translation, anti-disciplinary research practices, education, and radio. She is a former Young People’s Poet Laureate for London and Frontier-Antioch Fellow at Antioch University (Los Angeles). She has completed residencies at St. Paul’s Cathedral and the British Library, and has won an Eric Gregory Prize. Bad Diaspora Poems, her debut poetry collection, was released in Summer 2023.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.