We are delighted to share with you our favourite poetry books of the year!

Although it’s been a difficult year, where we couldn’t attend readings or poetry events in person, it has – nevertheless – been filled with exciting poetry, featuring long-awaited debut collections, innovative experiments, and fantastic books from long-established poets. There have been collections that have reminded us of the importance of friendship, joy, intimacy, and community, in a time when these things were scarce. These books kept us company when we could not be in company and provided some the best poetry we read this year.

We hope that you enjoy reading this list (presented in no particular order) and maybe even find some Christmas gifts for friends and loved ones! The team has made some personal recommendations of their favourites from the year, followed by a longlist of books we all thoroughly enjoyed.

I’ve been waiting for this collection from Daisy Lafarge since her first pamphlet, understudies for air, caught my attention back in 2017 – being one of my top books of that year – and it did not disappoint. Moving forward from that pamphlet’s conceit (the Greek philosopher Anaximenes’ assertion that air was the primary substance of all things), this collection riffs on Louis Pasteur’s observations on the processes of fermentation, as ‘life without air’, and explores moments, characters, and environments in states of literal and metaphorical airlessness and asphyxiation. Lafarge is writing a truly innovative poetry here – ecologically focused, keenly feminist, scientifically rigorous, and suffused with experimental sensibilities that challenge a host of contemporary thinking on misogyny, inconsistency, and our relegation of the non-human. This is a book for precisely the current moment and comes just in time, with the events of 2020 thrown into further relief by Lafarge’s writing:

have you ever festered

in your own quarantine, afraid

that your toxins would spread, only to find, when you finally

seep outside, that your sickness has turned benign

as if the very air

could oxidise pain?

In its dredging of lakes blighted by green technology’s mineral mining and picking through the wreckage of poisonous relationships, Life Without Air takes a hard look at humanity’s entanglement with toxicity and offers us a clarion call for change.

– Andy Parkes, Head of Programmes

Perhaps I should declare a vague conflict here as Glyn is one of our two brilliant MA tutors? But then, why the hell should I? It is a book I would include in any favourite list.

How The Hell Are You dances to the music of our times yet enfolds within its pages rhythms, craft, sensibilities, and questions which are timeless. From its eerily prophetic cover (chosen before COVID kicked us all into masks and face coverings) it is political in a universal sense, truthful in an existential fashion, and impressive in its control of form and language. In many poems, the reader is cajoled, assaulted, buffeted, and, indeed, charmed by a variety of disembodied voices which challenge and engage in a fashion redolent of Beckett – which kind of makes sense as Glyn is not only a poet, but a lyricist, dramatist, game conjurer, and much more besides.

It may be me, but I found myself quietly smiling as whispers of Eliot, Marvell, and other friends drifted from the pages, and all I might do is recommend that if you truly love poetry, its craft, its history, its future, and its power to provoke and agitate, then treat yourself to this book.

– Sally Carruthers, Executive Director

As a student of Rachel Long’s, I have long waited for her debut collection, and the wait was very much worth it. Nothing could have prepared me for the deep pulsations that each of these poems gave me.

My Darling from the Lions is a refreshing commentary on childhood, mixed race identity, womanhood, family, and sisterhood. These poems are filled with wry truths – ‘I feel middle class when I’m in love’ – that elicit laughter while holding a mirror to their readers that questions their laughter in the same breath; each poem unveils a heavy urgency that is lightly dressed. Long uses this humour and lightness of touch to comment on brutal, horrific experiences – illuminating how innocence and fragility can also be violent; such as the poem, ‘Interview with B.Tape II’, where a Barbie doll coyly narrates a cold-blooded racist attack that she initiated, as she was being ‘protected’.

At heart, the collection is an archive of family, friendships, and the author’s relationship to the Black women in her life and lineage. At times it reads like a photo album, including people ‘from all over the estate’ in movie-like scenes, but quickly tosses the reader back to real life, with the ‘gaffer taped loo’. In ‘A Lineage of Wigs’, beautification ceremonies and haircare practices are preserved through Winnie Mandela, a midwife, Auntie B and the speaker’s mother’s snake. This section starts with a very clear declaration of this history:

Mum combs her auburn ‘fro up high.

So high it’s an orb.

Everyone wants to – but cannot – touch it.

This collection will bring you to your knees – I cried, laughed, and laugh-cried all at the same time. Each poem will grab you and eat you whole!

– Esther Heller, Digital Programming and Marketing Officer

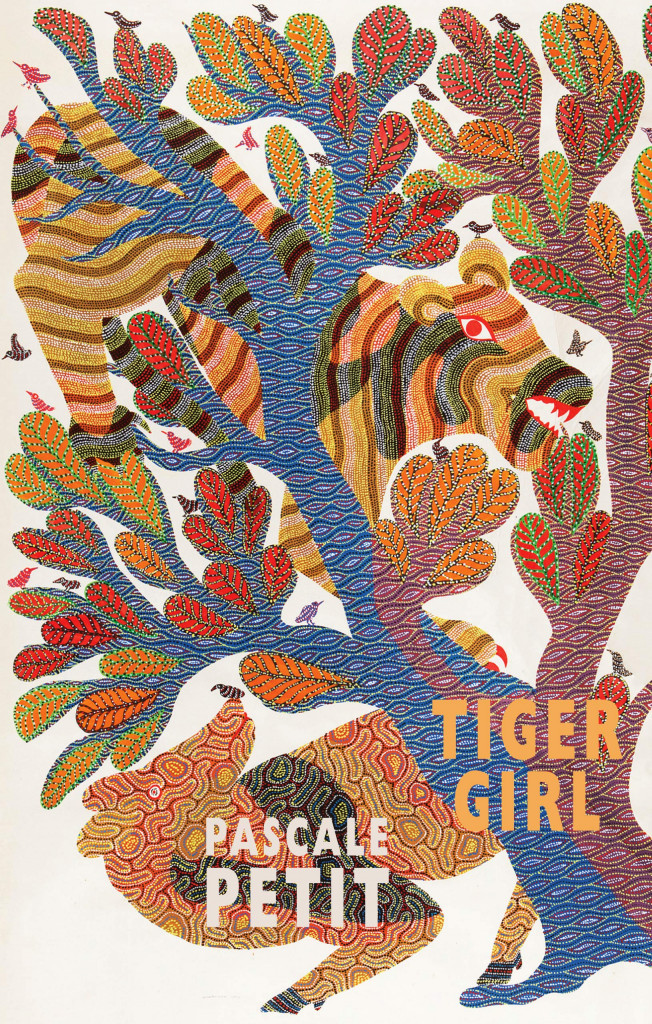

Tiger Girl by Pascale Petit is preoccupied by place, as was Petit’s previous Laurel Prize winning collection Mama Amazonica. The latter was set in the thick heat of the Amazon Rainforest, exploring nature, wildness, and extinction. Tiger Girl is instead set in central India, continuing to explore similar themes. The poems are strewn with jewels, rich fabrics, endangered animals, and the humans who treat them cruelly. Her work is about origin: where Mama Amazonica zoned in on Petit’s own Mother, Tiger Girl twists the lens onto her Indian Grandmother, whom she was raised by (Petit grew up under her care in Wales). Petit shows us how the places of our past live inside of us; how your country of origin snakes into the psyche and defines you, even when you are thousands of miles away from it. She interweaves the domestic with depictions of forests, poachers, and wild animals. Her luminous language brings India to life: the speaker is able to walk through the dank canopies of its jungles even when sat in a cottage in Wales.

Tiger Girl is also preoccupied by the maternal, the animal connection between mother – or, in this case grandmother – and child. In the poem titled ‘My Mugger Crib’, the speaker is a baby with a wild animal mother: ‘Mother whispers bedtime stories, what my crib eats, the deer she drags underwater’. Through playing with this bond she highlights the animal within the human and vice versa. It’s a fixation that runs deep, through generations and species. Her words expose the connection between humans and the earth: it is true ecopoetry. It is impossible to read Pascale Petit without dwelling on the most significant mother of all: mother nature herself.

– Jasmine Ward, Ginkgo Prize Manager

Wayne Holloway-Smith’s second collection, Love Minus Love, takes the form of a long sequence of untitled poems, where moments, phrases, and even individual words bleed into each other, deconstructing notions of a singular ‘speaker’ and transforming the sequence into a fragmented pattern of recurring, intrusive anxieties. It’s a book preoccupied with trauma and harm, at both the individual and societal level: self-abuse in unhealthy consumption, violence of the meat industry, toxic masculinity, domestic violence, socio-economic oppression of the working class, absence, bereavement, sickness. But amongst these blistering critiques there is also love, tenderness, and hope – in exploring these traumas and exploding the lyric ‘I’, Love Minus Love expresses a hope for a better, kinder future where mothers thrive, fathers are present, and:

yoube

come

strong

doing

theth

ingsy

ounee

dtobe

stron

gfor

– Andy Parkes, Head of Programmes

Having devoured Passivity, Electricity, Acclivity, with eager-fingered delight, wanting more when it was over, it seems I was not the only one, as the wonderful Offord Road Books has presented us with Shine, Darling which folds the pamphlet within its pages.

Shine, Darling is a delight, a heat-soaked, fleshy, provocative exploration of the maelstrom of the feminine. It glories in the sticky realities of love and lust, the longing and guilt inherent in adolescence, and beyond, then plays this out across a patchwork of forms. All of creation converges here, ‘the tiny thud of a rabbit’s heart’, deer, cats, ducks, llamas, bulls, dogs, snakes, slither, lick, and wander through the poems, and the corporeal, the senses made flesh, are a sustained murmur throughout the work.

I love this collection for its veracity, its joy and honesty, and its celebration of the messy, gorgeous glory that is life.

– Sally Carruthers, Executive Director

Will Harris’s debut collection is many things at once: playful, innovative, philosophical, tender, but most of all it is ‘questing’ – a word Sarah Howe uses in the quotation that appears on the back of my copy. Identity, culture, and history are explored from a range of perspectives, never quite arriving at a conclusion, but raising vital questions along the way. Throughout this impressive work, Harris challenges notions of the possibility of a single, cohesive identity (‘OTHER, MIXED is what I tick / in forms though […] I theorize my own / transmembered norms’) in formally experimental and technically accomplished poems that expand the lyric mode in exciting and rewarding ways.

RENDANG continuously draws attention to, and plays with, the materiality of language (the book opens with a list of words from the OED, starting with the word ‘REND’), insistently asking of itself ‘What are you trying to say?’, ultimately revealing language (both written and spoken) to be a vessel for imperfect attempts at assertions of selfhood (‘Whether you speak up or scarcely whisper, / you speak with all you are’). Despite their inevitable failings, literature and speech are presented as acts of hope, since they strive for connection: ‘You hear me, though?’. RENDANG is a stunning collection from one of the most important new voices in British (and global) poetry.

– Sarala Estruch, MA and Editorial Manager

Romalyn Ante and I met at a poetry workshop organised by another incredible poet, Alice Hiller. From our very first conversation, I felt a profound connection with Romalyn, who so inspiringly manages to balance her dedication to health and caring for others with her immense passion — and talent — for literature. I was over the moon to be able to read her debut collection, which was not only visually beautiful but also showed absolute mastery over the written word. I don’t think it’s easy to incorporate medicine into poetry, but Ante does it with such ease; the corporeal in her poems is always a representation of a relationship, of care, of compassion, even when it is intertwined with the political dimension of healthcare. But it is Ante’s poignant, beautiful, and meditative writing on movement — living in a foreign country, being away from one’s family, speaking a language not quite your own — that has moved me to the core. The feeling of uprootedness and longing permeates the whole collection, from ‘To Die a Little’, about being the ‘left-behind’, to

where it is the narrator who finds herself away from her homeland, her ancestry and her language. Learning, forgetting, and relearning languages is a crucial part of the collection, presenting this as a foundation of movement and of life away from one’s motherland.

Antiemetic for Homesickness makes me think that moving from one’s homeland changes us irrevocably, taking something away — the path to our house in our memory, the stories of our grandparents, our full names — filling us with a recurring sense of guilt for leaving something behind, but it also gives so much in return. Freedom. Nostalgia. Hope. This is possibly the most beautiful thing I have read this year. ‘No move is unplanned.’ (‘Checkmate’)

– Maria Lewandowska, Administration Assistant

Latinx writing and poetry is one of the most exciting discoveries I have made of late – not least, thanks to my dear friend Natalie Teitler, who has championed a huge number of writers in this area for the benefit of us all.

Mojave and Latinx poet Natalie Diaz’s second collection explores conflicts; of self, wars, the environment, family, heritage, and empire. As its title (and first poem) make clear, ‘The war ended’, but such a statement is entirely meaningless as war piles upon war, onwards through the ages ‘lost and won’, while a hope for peace – post-, or indeed pre-, colonial – is futile. Conflict is emblematic as existence itself; like a shark swimming, if we stop we die.

This is a collection for anyone who has ever felt marginalised or different, the dedication is to ‘…the missing and murdered Indigenous and Native women, girls, trans women, nonbinary and two-spirit people in our families, communities and across the Americas and other occupied lands’ and yet it is a book for us all, a book of conflict, the lines of which, the vibrant phrases and stanzas, might yet bring us all closer to a place of peace.

– Sally Carruthers, Executive Director

Timothy Donnelly’s latest collection is a staggering achievement. It’s a hefty book exploring a philosophical conceit – namely, problems of omission and exclusion in demarcating collectives of multiple entities – that deftly balances complexity and rigorous thinking with a breezy, conversational tone, wide-ranging references, beautiful musicality, and masses of pop culture, which makes for electrifying reading. This ‘problem of the many’ conundrum is applied to a host of examples, zooming into various collectives to explore their fractal complexities – be that clouds composed of vapour (from Peter Unger’s 1980 essay, from where the collection draws its title), a swarm of bees, oceanic water droplets, stars in the sky, bricks in the Tower of Babel, digits in large numbers, scales on a pinecone, grains of pollen, species in nature (and those lost to extinction), individuals in a population, poems in this collection, words in their lines. These thought experiments work brilliantly to elucidate the problems of overlooking the few when trying to comprehend the many and, in so doing, transforms into an inclusive presentation of the human condition – grieving humanity’s ever-increasing damage to the natural world and ongoing social injustices, whilst also revelling in our many joyous moments and expressing hope for a better future, a kinder present, and a more careful, nuanced understanding of our place in this multifarious world.

– Andy Parkes, Head of Programmes

How To Wash A Heart is Bhanu Kapil’s sixth book, and her first UK-published work. Having admired Kapil’s groundbreaking experimental poetry for years, I’m delighted to see her work finally beginning to receive wider recognition here in the UK. This collection is remarkable for its intimate probing of the guest-host relationship, specifically that between an immigrant guest and a citizen host, and the almost surgically precise way in which Kapil details the microaggressions that the immigrant guest has to endure, and which – over time – create tangible damage to the immigrant heart.

Like Kapil’s earlier works, this book is concerned with the body and language’s effects on it. I won’t spoil the book for readers by giving away the ending, but reading the final words had a visceral effect on me, pausing my heart for a few moments as I soaked in their meaning. The work takes on a heightened potence when reading it during the pandemic, where we have all been forced to spend so much more time ‘at home’ and have come to appreciate the importance of a safe space to recuperate from the challenges of the outside world. What happens to a person (to a ‘heart’) when one’s ‘home’ or place of rest is precarious, unsafe? How can an immigrant ‘wash’ their ‘heart’ of the stress-wounds that have been inflicted upon it, and retain the strength to survive – even thrive – emotionally and creatively? These are some of the questions posed by this timely and vital work.

– Sarala Estruch, MA and Editorial Manager

This book is a gift to yourself, your friends, your family, and everyone you love. As I could not gather with my friends this year, I have gifted this book to them as a replacement and reminder of joy, in spite of having so many odds set against us.

The opening poem is a sermon of another world, a litany of all the people that could be presidents, such as Rihanna, a trans girl, Nate Marshall, and ‘the leather daddy who always stops to say good morning’ are all the speaker’s president. The collection reads like a diary, as confessions are made to friends and family. It is a eulogy to friends that have been lost and a celebration of life at funerals. Danez Smith does not sugarcoat the real dangers that are killing Black, queer, and trans people every day and yet, this collection still hails praise: listing reasons (such as chosen family and smiles) to keep on surviving and be joyous in this survival. Homie is a love letter to community and a celebration of differences, poignantly expressed in the lyrical poem ‘what was said at the bus stop‘:

still teach them to dance & your pain is not mine

& is no less & is mine & i pray to my god your god

blesses you with mercy & i have tasted your food & understand

how it is a good home & i don’t know your language

but i understand your songs […]

A beautiful collection that has brought a lot of joy to me and everyone I have gifted it to.

– Esther Heller, Digital Programming and Marketing Officer

Longlist of Poetry School Selected Books 2020

Veritas: Poems after Artemisia – Jacqueline Saphra (Hercules Editions)

and what if we were all allowed to disappear – Tania Hershman (Guillemot Press)

Hotel – Ali Lewis (Verve Poetry Press)

Citadel – Martha Sprackland (Pavilion Poetry)

The Air Year – Caroline Bird (Carcanet)

Rootstalk – Ella Duffy (Hazel Press)

回家 Letters Home – Jennifer Wong (Nine Arches Press)

Poor – Caleb Femi (Penguin)

Delicious All Day – Alex MacDonald (Sad Press)

Deformations – Sasha Dugdale (Carcanet)

The Geez – Nii Ayikwei Parkes (Peepal Tree Press)

Cannibal – Safiya Sinclair (Picador)

Tongues of Fire – Seán Hewitt (Cape)

Between the Islands – Philip Gross (Bloodaxe)

The Shooting Gallery – Carrie Etter (Verve Poetry Press)

Return by Minor Road – Heidi Williamson (Bloodaxe)

Magnetic Field: The Marsden Poems – Simon Armitage (Faber & Faber)

The Actual – Inua Ellams (Penned in the Margins)

Saffron Jack – Rishi Dastidar (Nine Arches Press)

Sanatorium – Abi Palmer (Penned in the Margins)

Odyssey Calling – Vahni Capildeo (Sad Press)

Cloud Study – Sam Buchan-Watts (if a leaf falls + glyph press)

Big Sexy Lunch – Roxy Dunn (Verve Poetry Press)

Progress: Real and Imagined – Oli Hazzard (Spam Press)

Bad Moon – Samantha Walton (Spam Press)

Lean Against This Late Hour – Garous Abdolmalekian, translated by Idra Novey and Ahmad Nadalizadeh (Penguin Poets)

Runaway – Jorie Graham (Carcanet)

My Little Brother – Christel Wiinblad, translated by Malene Engelund (Valley Press)

Just Us – Claudia Rankine (Penguin)

The Martian’s Regress – JO Morgan (Cape)

The Taxidermist – Shazea Quraishi (Verve Poetry Press)

Locating Strongwoman – Tolu Agbelusi (Jacaranda Books)

Arrow – Sumita Chakraborty (Carcanet)

Hinge – Alycia Pirmohamed (ignition)

Somehow – Helen Calcutt (Verve Poetry Press)

TONIPOEM – Victoria Adukwei Bulley (Bad Betty Press)

Greenface – Anita Pati (Bad Betty Press)

Magnolia-木蘭 – Nina Mingya Powles (Nine Arches Press)

A Terrible Thing – Gita Ralleigh (Bad Betty Press)

bulbul calling – Pratyusha (Bitter Melon)

Wild Peach – S*an D. Henry-Smith (Futurepoem)

Passport to Here and There – Grace Nichols (Bloodaxe Books)

Beethoven Variations: Poems on a Life – Ruth Padel (Penguin)

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.