Kindles, Nooks, iPads, Portable Reader Systems – for some, electronic books are an ingenious invention. Slender and lightweight with vast storage and interactive controllable viewing screens, they are the latest stage of evolution for the book in today’s digital age. And so why do I shudder at the thought of empty bookshelves and identical interfaces? With all these whizzy, easeful gains – what’s lost?

Walter Benjamin hits the nub in his excellent essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction’ when he refers to a work’s “aura”: “that which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction is the aura of the work of art”. This is linked to authenticity, a work’s “presence in time and space, its unique existence”. Instead of transitoriness and reproducibility, it has uniqueness and permanence.

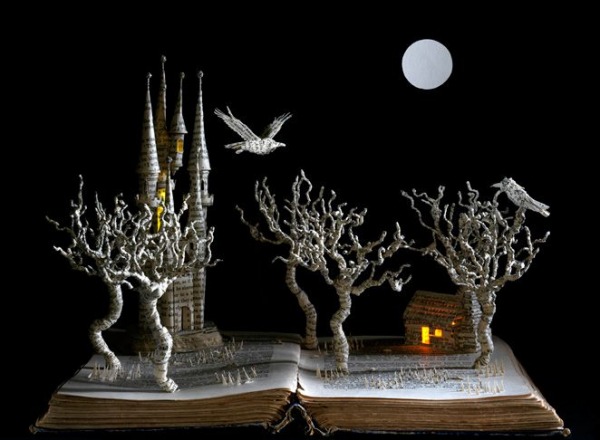

What better example of a work brimming with aura than the ‘artist book’? Visually stunning design in limited print runs or as one-of-a-kind art objects, they defy any attempt of reproduction. Later on, I’ll pick out some sumptuous examples – but first, let’s see how we got to where we are today and meet some illustrious ancestors of the eBook by enjoying a short, visual history of ‘the beautiful book’. (For a more verbal historical overview, I recommend A Companion to The History of the Book, ed. by Simon Eliot and Jonathan Rose).

Developing from the clay tablet and papyrus roll, the first books or ‘codices’ (from Latin caudex ‘trunk of a tree’) were mainly used in religious contexts for sacred texts. And they had to be beautiful, because form reflected content: the majesty of God’s word. Costly materials included parchment, vellum, leather, coloured inks, pigments, gold leaf, metalwork, ivory, gemstones, treasure bindings; the books themselves became symbolic objects of veneration. A few party-poopers objected to the seemingly idolatrous status of these man-made creations (some scribes and illuminators made deliberate mistakes to humbly distance themselves from ‘perfection’). But, being so expensive to produce and employing a number of craftsmen, most were rather special, reflecting also the status of their eminent owners: the Church.

At first, low levels of literacy made books even more rare, but gradually they became something you could enjoy and own privately (albeit in wealthy households). For example, the ‘books of hours’ – devotional aids that laypeople, especially women, could have to follow at home. How gorgeous these could be! Often with personal additions, such as the family’s patron saint, that made them unique.

Break-through technology thrust itself onto the scene in the mid 15th century, with Johannes Gutenberg and his movable type printing. A subsequent shift from the uniquely handmade to the mechanical multiple introduced a whole new market of lay readership and the birth of the book trade. Instead of colourful calligraphy and painstaking illumination, we have feats of typography and intricate engraving. The books featured precision and symmetry rather than quirky irregularities.

The nineteenth century saw even more industrial innovations that revolutionised the book making process, including the Fourdrinier papermaking machine and the steam powered rotary printing press. To put it in perspective, a Gutenberg-style press (ca. 1600) could print 240 impressions per hour; the Koenig press (1818) could print 2,400.

This is the context William Morris and the Arts and Crafts movement (mentioned in an earlier piece on craft) were reacting against. Harkening back to a preindustrial age, they championed the ‘handcrafts of bookmaking’, using the finest techniques and materials – and humans!

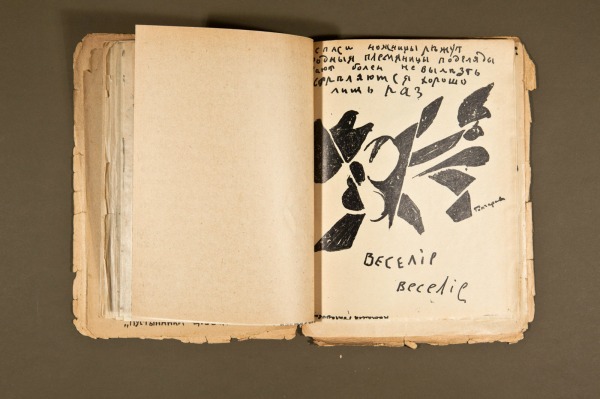

In the early twentieth century, things became edgy. Avant-garde artists created work that reflected Modernist sensibilities: futuristic, stark, jaunty, explosive.

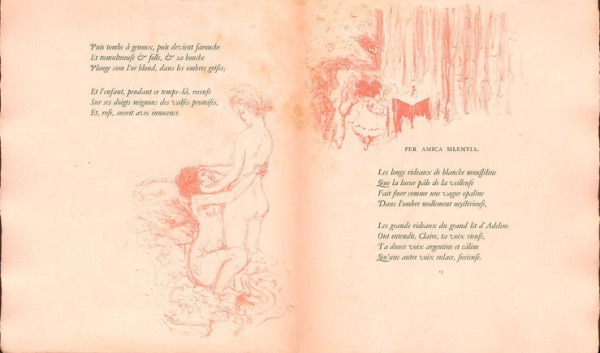

This is also the time when the livre d’artiste “artist book” originated as a genre of its own. Megan L. Benton, author of Beauty and the Book, pinpoints it to 1900 when Ambroise Vollard (the same man who commissioned Picasso’s famous ‘Vollard Suite’ etchings) published Parallèlement, a lovely work combining Paul Verlaine’s poetry with lithographs by Pierre Bonnard.

Benton defines an artist book as “a new genre in which imagery was deemed as important a factor in a book’s design as its text” where “visually inseparable, image and text were perfectly married”. Experimental, tactile, subversive, extravagant – artists embraced ‘the book’ as a new surface to explore, pushing the boundaries of what its material form could achieve.

Today, thankfully, these kinds of books are still being made. I featured The Whittington Press and some of its gems in my last piece. I currently work at Enitharmon, which has not only its poetry list (Enitharmon Press), but Enitharmon Editions – a series of artist and writer collaborations. In an article for Parenthesis, director Stephen Stuart-Smith explains:

In an age of e-books and digital printing, it may seem perverse that a dwindling band of publishers persists in making artists’ books, but as readers of Parenthesis and Matrix will be the first to know, there is great satisfaction in maintaining the highest standards of book production and in marrying text and image through creative partnerships. Miraculously there are still libraries, museums and private collectors eager to buy the modern equivalent of the livre d’artiste, especially if the artist and writer enjoy high reputations and their collaboration results in a beautiful book. As an artistic activity, it satisfies every aesthetic craving; as a commercial enterprise, it makes no sense at all, and trade and print publishers would be aghast at the economics. All the more reason to continue, as evidence not only of the imaginative force of artistic partnerships, but also of the health and excellence of typographic design, letterpress printing, hand binding and papermaking.

There’s a hearty list of stunning examples if you search ‘artists books’ on the V&A National Art Library catalogue. These kinds of books are imbued with ‘aura’: not withering but blossoming in the face of mechanical reproductions and electronic technologies.

And yet, I would argue that every physical book has an aura of its own – if not at first when fresh from the printers, then developing over time. Its smell, stains and signs of wear; personal associations from how we acquired it, where, by whom and at what time in life; memories of a former reading experience or anticipation at a first. Each book is an organic object; once owned it belongs and becomes part of us, waiting to be picked up and wondered at.

Thanks Lavinia so much for such interesting Blogs and introducing us to such beautiful books. One I have and love is a Harry Clarke illustrated The Year at the Spring.

Thank you for such an inspiring article, and thank you for such a wonderful selection of illustrations. I wanted to touch, smell, read and savour, but oh horrors, I have to read through my laptop screen and I feel bereft!

Reply to Olivia: Thank you for your nice words! I completely agree with you – it’s a measly way of experiencing these works, but at least they’re out there, somewhere, in all their physical glory!

Reply to Ita: I’m so pleased you’re enjoying it, thank you for saying so. And Harry Clarke is one of my FAVOURITES! I actually have mentioned him in my forthcoming piece on ‘The Art of Illustration’, in connection with a spellbinding exhibition at the Dulwich Picture Gallery a few years ago called ‘The Age of Enchantment’. That’s a very lovely book to have on your shelf!

Lavinia. You quote from Megan L. Benton a two part definition of an artists book: “Benton defines an artist book as “a new genre in which imagery was deemed as important a factor in a book’s design as its text” where “visually inseparable, image and text were perfectly married”.” What is your source for this quote. I have been looking for it an could not find it. Please let me know. Thanks.

Hello, the quote comes from A Companion to the History of the Book, edited by Simon Eliot and Jonathan Rose. You can find the first part of the quote here on Google Books: https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=CFiDCjMcnvcC&pg=PA502&lpg=PA502&dq=a+new+genre+in+which+imagery+was+deemed+as+important+a+factor+in+a+book%E2%80%99s+design+as+its+text+megan+l+benton&source=bl&ots=NlIF31Gjot&sig=ACfU3U2KnRz-jiTFafwTSA65N0h-ggoESQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwi3hMHo8PzfAhVxVBUIHfEnDrcQ6AEwB3oECAQQAQ#v=onepage&q=a%20new%20genre%20in%20which%20imagery%20was%20deemed%20as%20important%20a%20factor%20in%20a%20book%E2%80%99s%20design%20as%20its%20text%20megan%20l%20benton&f=false