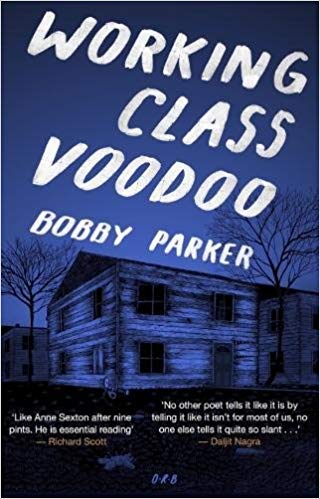

While Working Class Voodoo knowingly writes into and through traditions passed down from Anne Sexton, Robert Lowell and other ‘confessional’ writers, Bobby Parker is, emphatically, a poet of his own, disrupting what we expect from the lyric ‘I’.

Working Class Voodoo provides the uncomfortable yet absolutely indispensable vantage of being a moth in the carpet of Parker’s life and imagination, allowing for numerous bitter-sweet riffs on class, drug dependency, families, masculinity and austerity.

There seems little doubt that, in original draft form at least, these poems arrived very quickly. And while the book sustains the brisk pace of a poet writing as though his life depends on it, the lingering impression is one of meticulous construction. I read many of these poems rapidly – a staccato mix of very short and longer, run-on lines forcing the eye to do so – but then immediately felt the need to begin again, reading slowly, teasing out details. A stand-out poem (amid many highlights), ‘Killing Spiders’, sees Parker taking aim at performativity:

It feels like we should stop

indulging poets who write

as if they’re not even breathing

tell them fuck you

for making me hold my breath

Centring around a panic attack – ‘halfway through this poem / my lungs were almost out of credit’ – a self-reflexive Parker describes how ‘when I put my fingers down my throat / it’s like I’m trying to touch another person / it’s like I’m searching for the light switch’. If ‘confessional’ has become a rosette worn to signify ‘authenticity’, Parker wants to rip it off. ‘I’d rather die in a poem / with my balls so tight I’m basically angelic / with my arsehole / sore from shitting bricks in London’, he declares; the brash demotic is perfect for a poet eager to challenge the staid registers which would pigeonhole autobiographical poetry as being a middle-class pastime.

In ‘Tiny Skulls’, reminiscent of Plath as much for its deft use of repetition (‘machines machines machines’ put me in mind of ‘Daddy’) as for its subject matter, Parker worries that the hyper-masculine presence next door, ‘his voice like scrambled eggs’, will continue ‘calling me a cunt because I don’t / work in a factory’. A microcosmic portrait of a divided country, ‘Tiny Skulls’ exposes how ‘It matters so much to him [the neighbour], it matters so much / to her parents and my parents and the local newspaper.’ Born and currently residing in Kidderminster in the West Midlands, the small-town asphyxia permeating these poems can be read as Parker’s foretelling of post-Brexit Britain, but the presiding theme is how an individual’s agency hinges on conflicting social and personal factors, the poem becoming a space in which to sculpt fury: ‘’Shut the fuck up, it’s time to light the fire.’’

Two poems near the end of the collection, ‘Schnook’ and ‘Swine’, approach the polarities of small-mindedness. The latter has Parker ‘trying to think of something to say’ after being told by a taxi driver about Islamophobic vandalism: ‘Then there was rotting pigs’ trotters / hanging from door handles / and dark blood splashed up the walls.’ A poem which bears witness to the rise in xenophobia and far-right sentiment, both the driver, ‘who couldn’t hear me / over the sudden boom of taxi jargon’ and speaker, wondering ‘Where did they get all them heads from?’ become implicated in a narrative which cautions against binary tellings of Brexit. ‘Schnook’, meanwhile, paying homage to Goodfellas, contemplates the would-be Stockholm Syndrome of moving from ‘days of scoring, using, scoring, waiting’ to a ‘perfect home’ and the accompanying ‘silence of living / at the edge of the countryside’, before pondering, doubtfully, ‘I won’t miss it at all.’

Questions – ethical, personal, political – of transformation versus stagnation lie at the heart of the book. ‘Ginger’ is a stunning example:

I ask her to turn me into a pretty girl,

not drag for laughs like Jimmy

whose whisky makes me gag.

.

His frightened wig

the candyfloss of demons.

.

She empties her make-up bag

on the floor, a bird’s-eye

view of the fair.

Just pause for a minute to consider these nine lines as an opening. Such bravado combined with such particularity! And that image: ‘wow’ is the appropriate word. When later the make-up artist’s ‘smile as she works’ is compared to the ‘special kind of weather / reserved for mountaintops’ and the poem ends with ‘Jimmy’s drugs were cut with sugar’, the only response it to applaud Parker. Take another example, ‘Silver Thumbs’, full of droll humour:

I think about my doctor

washing his hands

a hundred times a day

telling me I need to stop obsessing.

If ‘/’ initially appears banal in its describing ‘holding her warm little hand’, that’s only because ‘holding each other / is the beginning and end of the universe’. The appearance of Parker’s daughter – ‘Isobelle I cried Isobelle it’s Isobelle’ – performs a kind of black-hole folding: a vacuum in to which all other concerns shrink and crumple. Isobelle’s presence in the book becomes cathartic, symbolising an open-ended future which stands in brave opposition to the claustrophobia and anomie presented elsewhere. In the final poem, ‘Rocket’, Parker reflects on the passing of time ‘wondering / what the hell happened’:

It’s easy to forget there is such a thing as beautiful

when we’re shivering in the park

worried about our children

losing what we lost.

‘Piñata’ clashes everyday domesticity with long-term depression, resulting in a tender commentary on age, parenting and jealousy. Parker’s real talent is his ability to imbue these otherwise-throwaway items (literally, in the case of the cat litter tray) with gravitas; exploding the strictures of the ‘traditional’ family unit. ‘I could still smell cat piss’, he writes, ‘even though we bought / a more expensive litter box / with a roof and a door / to contain the odour.’

If some of the shorter poems are concerned with home and home-making, it is in the longer poems that many of these ideals are tipped on their head. ‘Binge-watching Bad Memories’ unsettled this cozy reader. As an extended exercise in the free-indirect style, it takes the baton from confessional poetry and hurls it aside. The poem is too long, too complex, to quote from arbitrarily, but like many of the other rangy set-pieces in Working Class Voodoo, it succeeds by punctuating a multitude of calamities with moments of exquisite lucidity. A line like ‘to kiss her out of her bones’ shows that, while these poems find their genesis in moments of crisis, their honing is an exacting art.

Working alongside recent books like Melissa Lee-Houghton’s Sunshine, Working Class Voodoo sets out to strain life through the sieve of poetry. In doing, it teaches us new levels of empathy, foregrounding the personal amid this tumultuous political moment.

You can find out more about Working Class Voodoo from Offord Road Books.

You can find out more about Working Class Voodoo from Offord Road Books.

If you’d like to review for us or submit your publication for review, please contact Ali Lewis on [email protected] or Will Barrett on [email protected]

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.