In this first instalment of our Ted Hughes Award ‘How I Did It’ series, Harry Man explains the creative process behind his shortlisted work, Finders Keepers, created in collaboration with illustrator Sophie Gainsley.

Finders Keepers is a collaboration between poet Harry Man and artist and illustrator Sophie Gainsley that examines Britain’s vanishing wildlife. Poems from the project are hung and geocached in public spaces across the country to memorialise these lost voices and to celebrate some of the success stories of species brought back from the brink and the conservation of British woodlands, hedgerows, rivers and other wild habitats.

Ted Hughes’ line, “Anything you throw in the ditch ends in your cup,” has been lodged in my head for a while. Hawk in the Rain, Hughes’ first collection was published in 1957, meaning that this year it will turn sixty. It’s a book of violent miracles and Hughes’ influence, and Sylvia Plath’s, live on in contemporary nature poetry, and it’s difficult, once in your ear, to remove their voices entirely. Writing Finders Keepers, I wanted to take a poem for a walk to see where constraint might take me at one end, or total freedom at the other in order to create living, almost holographic portraits of the animals inside.

These had to be poems that interacted with their illustrations – and that played like different light along the walls, lapping and overlapping. I wanted the notes in the back to feel upbeat and to share the sense of getting reacquainted with parts of the natural world from which – like most of us – I had become alienated. Alice Oswald’s collaboration with Jessica Greenman, Weeds and Wildflowers is a beautiful book in which the poems and etchings are separate entities that, nevertheless, cleverly, inseparably occupy the same artistic space, but I also like Chris Stephenson’s Constellations which is about Project MKUltra and that makes use of concrete shapes on the page, that are built, erased and eroded in front of the reader in such a way that you feel included in the experiments described, by turns, both to your horror and joy, similar in some ways to Leanne Shapton’s novel told in the form of an auction catalogue, Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris Including Books, Street Fashion and Jewelry. I also looked at poetry by Susan Richardson, Marianne Moore, Gary Snyder, Caroline Gill and Elizabeth Bishop. There was also Sandra Beasley’s remarkable poem, ‘Unit of Measure‘ and poems like those from Adrift, and Tom Chivers’ extraordinary psychogeographical work ‘The Walbrook Pilgrimage’. These all fed into the mixture. This is also coupled with my desire to put the robin in with the rubbish bag on the Christmas card and to give a voice to the lives in our parks, at our back doors and those that roost in our roofs. So it was a tall order, and I felt the pressure very keenly.

If you make the reader hesitate over a poem for long enough, you hope that what was there to begin with will magically appear, and much like the world I experienced in writing the poems – some of the time you may come up as a reader – empty. That is acceptable too, but it’s inherently risky as an approach. My skin frequently itched, and tingled with that risk – it still does.

Each poem arrives quite differently, and usually out of research. I immerse myself for long periods into my subject, and then I wait, and hopefully a poem will whisper itself to me. The whole process feels almost separate to who I am as a person; out of the silence, the lyric. This place of almost total passivity at the point of creation is the most ecstatic state of writing. I remember the story of William Rowan Hamilton, so overwhelmed by his discovery of quaternions, which arrived in a flash of genius that he scrawled the formula onto Broome Bridge in Dublin. This sensation of being gripped by something like voltage, is more or less what happens, and is what can’t be taught so easily. I can speculate and say that it’s about stimulating the anterior superior temporal gyrus (the part of the brain responsible for creative insight) through reading. Like the London taxi drivers with enlarged posterior hippocampi from learning ‘the knowledge’ your brain too, can acquire, assimilate and answer through the continual reading of poetry.

After this flash of insight comes what can only be taught: the point of typing up the poem, then a painstaking process of shaping and testing the lines, which goes on for several pages. I save each draft as I go, and in every iteration, I try to move the vocabulary on, and check the vantage points in the poem, to try to understand where it is we’re looking within the line, then through it. Most of my poems end up on the cutting room floor.

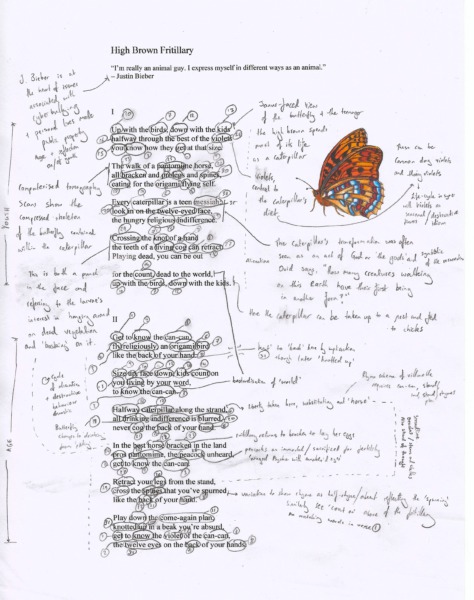

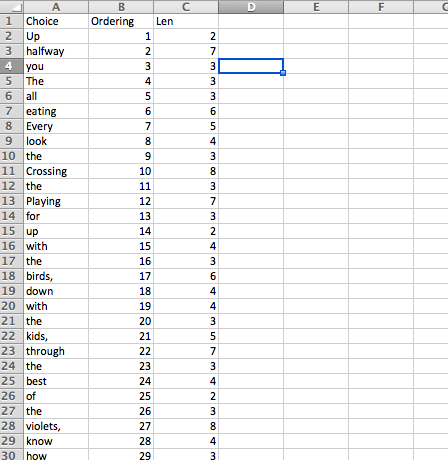

The more concrete processes, whereby a poem arrives via constraint endemic in the writing, are simpler to describe in detail. Very occasionally I will use Excel to design a poem. With something as conceptually complicated as ‘High Brown Fritillary’ (pictured above), my intention was to use the same words in both the first and second verse. Jon Stone invented the form, and offers the following definition:

“The poem comprises two stanzas, the second being a ‘transformation’ of the first and vice versa. ‘Transformation’ here is a flexible concept – many of the poems use word or letter rearrangement, while others use homophonic or calligrammatic mirroring.”

In addition, I wanted the poem to transform from a sonnet into a villanelle. At that point, you’re looking to fuse some of your knowledge about the butterfly, with a complex set of constraints. Using Excel, I can count words as I remove them, flag changes in sense, tense and rhyme, and I can cross-check between the two verses, to see what needs replacing (see below). Words are helicoptered in, or rushed away, and alternative verses kept intact over the page.

Some of the poems in Finders Keepers are assembled from transcription, or from quotation from what conservationists have said to me. This includes the remark that I might be ‘too young’ to know the phrase, ‘the pot calling the kettle black’ which worked its way into a poem in the shape of the UK. Others that didn’t make the cut included the gardener who told me about the time he picked up a bloke off the M6 who was dressed entirely in Roundhead civil war re-enactment gear and who was there because he’d had a fight with the driver, he said, of a Cavalier. I also wanted to talk about the night-runner beetle, but unfortunately it wasn’t to be.

Talking to Sidekick about typesetting the poems in the book, editor Jon Stone wrote to me about Sophie Gainsley’s dragonfly, and I wanted it to be interruptive within the poem, and to crash through the space on the page and he did an amazing job. Sophie’s illustrations lock eyes with the reader, and are so luminous, that plunging into the pamphlet, I am taken back to riding on my bike through the sustained artificial dusk of London, and cornering the road, where I see further ahead, the fox, its eyes looking not just at you but somehow into you. It’s little wonder why Hughes found the fox, his fox, his thought-fox so haunting.

Originally the pamphlet ended with a word travelling over from the last page. So in that white space at the very end of it, you’ll just have to imagine the word there in brackets, and that word is: (again)

Find out more information on Harry Man’s Finders Keepers project and buy the book at finderskeepers.org.uk

Find out more information on Harry Man’s Finders Keepers project and buy the book at finderskeepers.org.uk

Harry Man is a poet from South London and living in Teesside. Lift, his first pamphlet, won the 2014 Bridges of Struga Award. Harry was a 2016 Clarissa Luard Wordsworth Trust Poet in Residence and a 2016 Hawthornden Fellow. He is a 2016 TOAST Poet. His most recent pamphlet Finders Keepers about endangered species across the British Isles, is created in collaboration with the artist Sophie Gainsley and is shortlisted for the 2016 Ted Hughes Award for New Work in Poetry.

We have asked all poets shortlisted for this year’s Ted Hughes Award for New Work in Poetry to tell us about their writing process. For more blogs visit poetryschool.com/how-I-did-it

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.