Drawing on her childhood in Indonesia and her experience as a disabled artist, Khairani Barokka’s second collection, Ultimatum Orangutan, brims with vitality, wisdom, and courage. Moving effortlessly between the personal and the universal, between hope and despair, the poet questions the spaces and times we live in, the relationship between an individual and society, and brings home the necessity of resisting all forms of violence and systemic injustice that compromise our dignity or beliefs.

Using incisive language and exciting forms, Barokka’s work explores the issues surrounding disability, advocacy, and notions of justice along the anti-colonial praxis. In Indonesian, the language which Barokka grew up with, ‘Orang utan’ means ‘person, or people, of the forest’; throughout the collection, one is reminded of the fundamental relationship between land, mind, and the body, while destruction goes back to the origins of colonialism. Through Barokka’s poetry, we intimate a world where everything is connected.

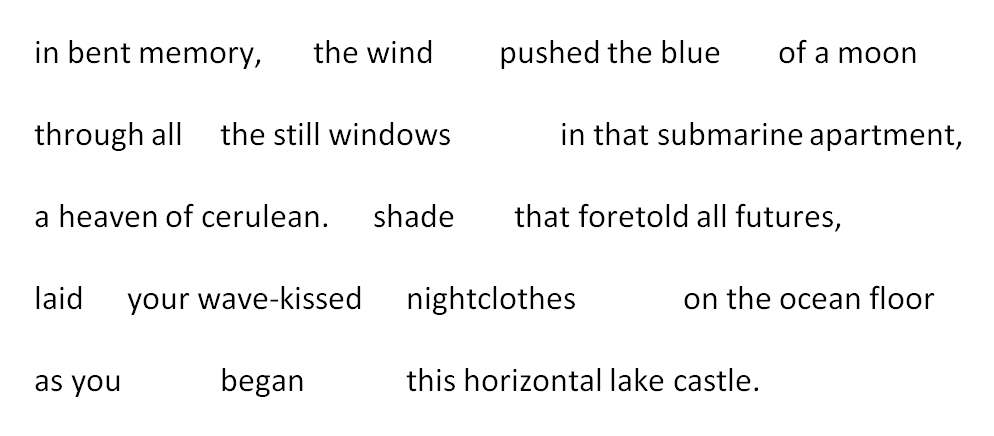

Bringing to her work her experience as a disabled artist, Barokka provides an exploration of the tension between one’s body and the mind. In ‘pain speaks to okka’, pain becomes a language or filter through which one experiences the world:

Here, pain is translated into an endless ocean that ‘foretold all futures’, while the spacing between these images and the broken syntax seem to act as ellipses, leaving the reader to speculate the source and trauma of the pain being conveyed. The surreal image of the ‘horizontal lake castle’ seems to suggest a castle that cannot fully contain the lake-like body of pain.

Bearing witness is a central focus in many of Barokka’s poems. In ‘tuban planting’, one is beckoned into the speaker’s mind and we are shown the creative process informed by bodily experience, where salvation is:

to close eyelids tensile and conjure

leaves upon my right-hurting side

like the cloth weaved in tuban, east java,

where yangti came from, where batik artisans

plant the vegetation themselves that will

one day be thread.

Earlier in the poem, the speaker opens with ‘fascia’ (a band or sheet of connective tissue) as a ‘conduit for rage’:

it tells me to lie down and write,

to sip warm tea with milk,

so i can regurgitate a many-storied anger

onto sheafs of dead trees.

From this deeply personal outlook, the poem then stretches its perspective to a wider, collective memory and social body of experience:

my grandparents grew from that soil,

[…]

with hyperskilled, threatened hands,

and burning-sick, tired bodies,

and the earthenness inside of them,

lives to die for a giving end.

Barokka’s use of form is refreshing and uncompromising. For example, in ‘Terjaga II’, the speaker connects the various visible and invisible forms of violence or oppression done to oneself or to others:

after the teargas, the blacked out words, ripped up books, banned

songs, packed prisons, threats to family, threats to self, lowering

our lives onto the sharp end of a knife, onto the sharp end of

brains too filled with injury, after erasure, after libel, after media […]

The repetition of the word ‘after’ merges with the complexity of a mind trying to contain these ‘many mass current and past resistances’. While the mind grapples with these tenses, looking to a future ‘after[wards]’, we are disrupted by an abrupt blank at the end of the poem. Though unnerving, the space also constitutes a clearing in which the reader is startled into planting their own ‘after’ thoughts. In this way, we are brought to account by the poem.

In ‘Fence and Repetition: A History of Climate Change’, the specular poem helps the reader to trace the ‘mellifluous thinking’ to the initial cause of ‘colonists’ decision / to ink signatures’, speaking out against damage to the ecosystem and wildlife while mocking the irreversible courses of action in history.

In ‘Situation report’, note how the poet creates a sense of urgency about the environmental threats through the use of repetition and the quick melting of ‘the rainforest tindering quick’ and ‘pulped trees for warnings’:

melt of the nation-states.

melt of the coastal tribes.

melt of the rainforest tindering quick.

melt of the quickening and left-for-dead

in industrial dumps. melt of pulped trees

for warnings to be read and cause insomnia,

melt of industrial revolution as imposed

upon former colonies, current colonies.

Here, this apocalyptic vision of the ‘melt with no name’ becomes symbolic of the suffering or breaking down of the world. There’s the urgency for one to heed these ‘warnings to be read’, to come to the world’s rescue, or else arrive at an irreversible situation.

In Barokka’s poems, we see poetic language in a state of flux. In ‘pylons’ — a confessional, intimate poem –, we are introduced to the first-person voice in crisis (‘writing from a drowning ship’) and we are confronted with the horrendous image of ‘a coral reef blasted’ and ‘the glow of a supernova / that is our own destruction.’ At the end of the poem, however, a softer, slower language of grief and compassion soothes the destruction that it has just come through:

I am the palms of your mother

in the dead of night,

when all rushes to extinction,

and constellations swarm your body,

reminding you of what is here still.

The last line directly addresses the reader, opening a glimmer of hope whilst warning us of what will become lost or endangered if action does not come soon enough. Through kaleidoscopic imagery and word choice that blends the cosmic with minutiae (‘when all rushes to extinction’, ‘the glow of a supernova’, ‘constellations’, ‘the palms of your mother’), we feel a deep sense of nostalgia for the world before its careless destruction.

Politically engaged and bold in its prophetic visions, Ultimatum Orangutan is an outcry against environmental hazards, social injustices, and racial and ableist stereotypes. Through the use of experimental language and forms, and surreal imagery, Barokka’s poetry exposes the underlying relationship between colonialism and environmental and systemic injustices, confronting the reader with crucial, thought-provoking questions about climate change and the treatment of indigenous societies, and forces us to contemplate the consequences of inaction.

Born in Hong Kong, Jennifer Wong has published several collections including 回家 Letters Home (Nine Arches Press 2020). She studied in Oxford and completed a creative writing PhD at Oxford Brookes University. She teaches creative writing at Poetry School.

Ultimatum Orangutan by Khairani Barokka (Nine Arches Press)

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.