– iron and haze –

blood is borne on the sea

an oil rig

births an unending rage

amuk

(‘amuk i. waters’)

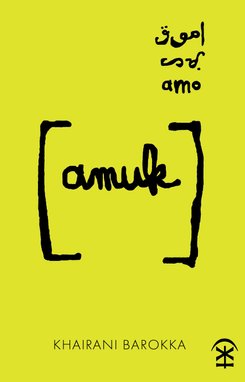

Khairani Barokka’s defiant and inventive third collection gives voice to ‘unending rage’ and grief in the face of extractive colonialism and environmental destruction. The collection touches on the impact of issues such as the commodification of rainforests and oceans, mining by overseas corporations, and the disregard for indigenous environmental knowledge. In ‘amuk ii. bedrock’, Barokka writes that in 2015 ‘nearly 100,000 children and adults in Indonesia alone / are killed by forest fire and smog’ – a statistic that ‘will not be mentioned in the press’. The title, ‘amuk, means “rage/to rage” in Indonesian and Malay’ and in amuk the term functions as collective rage and prayer, that acknowledges harm, allowing us to heal and resist (‘Notes’).

On Swallowed Tongues, and Quietening Forests

The collection opens with the experimental long-form poem ‘amuk’, which delves into the links between translation, colonialism, and the climate crisis. In ‘amuk [infinity symbol]. waters’, Barokka writes:

amuk is a rage that does not necessarily claim victims

turns into

amok is a homicidal psychopathology

and to run amuck is directionless

Mistranslation is a tool of dehumanisation and, at the hands of this English translation, justified anger becomes unruly, ‘feral’, animalistic, ‘homicidal’ aggression. When the purity of your rage is manipulated, there is no way to challenge injustice. Later, in the same poem, Barokka writes ‘the story of amuk / is that of tongues being swallowed whole / and ever-quietening forests’. Here, a language, a voice, and a body can be consumed in the same way that land can be bought, destroyed, and silenced.

Nothing Is Forgotten.

Barokka explores how language and grammar replicate the beliefs of a culture, and in ‘i. amuk | اموق’, she writes that ‘indonesian […] has no tenses.’ Time in amuk is therefore nonlinear and cyclical, and Barokka makes the English language reflect this. Verbs become past-present-future words, as in ‘amuk ii. bedrock’

when we said-say-will sa

these plants you destroy or consume

are our relatives

they will laugh

before they burn-burned-willburn them

When something happens, it is as though it has always happened and is always continually happening. When a language such as English confines our actions to the past, what implications are there for the climate?

In amuk nothing is forgotten. Colonial violence, genocide, and grief is ever present but, at the same time, no small voice of resistance can ever be silenced. Once something is said, ‘we said-say-will say’

“No” to Your ‘Nature’

Barokka’s use of voice and pronouns throughout the collection is inventive and effective. The ‘we’ of the collection is a collective voice of resistance. It is also a ‘we’ that does not exclude nature. In ‘i. amuk / اموق’, Barokka writes:

we, the voices of amuk, recall the following quote, from yoruba

philosopher bayo akomolafe:

‘what we rudely call ‘nature’ today does not even have a name in

Yoruba culture because there was no distinction between us and

the goings-on around us. […] mountains could be consulted, trees

could have privileges…

Community then, isn’t confined to human beings. The introduction of a separate word for ‘nature’ in western cultures allows for that nature to be treated as something separate to us, as an economic resource. Much of the collection is written in lowercase and the ‘i’ of the collection is also lowercase, a subtle rejection of English grammar and perhaps western ideas of the individual self.

Rage, in the Contemporary Environmental Space

Barokka also confronts the racism of contemporary environmental spaces. In ‘amuk iii. great fires’ a ‘white “nature writer”’ tells the speaker that ‘“i’m more worried about brexit than i am about climate change.”’ And in ‘amuk [infinity symbol]. waters’, the speaker is patronisingly told ‘i love your rage’ by a ‘former world leader’. Barokka fills an entire page with those echoing, cloying words: ‘i love your rage’. The distance between the ‘i’ who does not feel the same rage as the ‘you’, is pronounced. With each repetition, we feel the nausea of a pure rage being manipulated into something that is performed and consumed by a watching, detached audience.

Endless Prayer, Rage, and Peace

amuk is equally about prayer as it is about rage, and the final section of the collection is titled ‘doa’ which means ‘prayer / prayers’ (‘Notes’). These prayers praise, mourn, and remember. They are offered for people and for the elements. Barokka’s use of language and attention to the sounds of words creates fresh, surprising imagery here. In the final poem of the collection ‘doa tanah / dirt prayer’ Barokka writes:

lower me rooted,

soil-breasted

iridescent, brown,

calm with earthworms.

There is a sense of luminous beauty and harmony as the body returns to earth. We hear the echo of the words ‘brown’ and ‘calm’ in the word ‘earthworm’, making the image itself sound cyclical and peaceful. Here, the body is one part of the continuous cycle of nature and time, described as ‘flesh as rainforest and rice, endless.’

amuk is an ambitious and accomplished collection that wrestles with language, meaning, mistranslation and environmental crisis. In it, Barokka reclaims the power and purity of a rage that is working in tandem with love and community. There are also moments where the grief for what has happened, and what will happen, cannot ever be fully mourned or expressed. Poignantly, the last page of ‘amuk’ is enclosed by two page-sized images of the palms of a hand. And we see the shadow of fingers in a cupped position, the delicate lines of the skin as they hold the last words of the poem in silence, tenderness, and prayer.

Roshni Gallagher is a poet from Leeds living in Edinburgh. Her debut pamphlet Bird Cherry is published by Verve Poetry Press. She is a winner of the 2022 Edwin Morgan Poetry Award and the 2022 Scottish Book Trust New Writers Award. In her work, she explores themes of nature, memory, and silence. Find her on twitter and instagram or at roshnigallagher.com

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.