Music for the Dead and Resurrected, which won the International Griffin Prize for Poetry in 2021, is Mort’s third collection. The poems rove and hover over an icy, war-ravaged, politically-damaged Minsk (or ‘the hero-city of Minsk’ as the speaker in ‘Self-Portrait with the Palace of the Republic’ was forced to refer to it as in school), a city that came under rule of Nazi occupation during World War II. Many poems have refrains that shapeshift every time they recur. ‘Self-Portrait with the Palace of the Republic’, the first prose poem in the book, in addition to establishing the autobiographical backdrop of this collection, gives the many shades of Belarusian winters. Mort unceremoniously (in prose) lays them out like doctrines: ‘Winter is like being inside the static of an untuned TV… When I look out of a school window, it’s always a winter night, and there’s always blood in the snow.’ Later in the poem, the speaker describes ‘Operation “Winter Magic”’, an operation conducted during World War II by German-controlled Latvia, where ‘[s]everal hundred villages were burned with all the civil population gathered inside barns.’

Winter’s meaning modulates. Sometimes it’s a season of forebode and darkness, sometimes a temperature, almost always a word meant to denote humankind’s heinous capacity for human cruelty and silencing. ‘[T]here’s always blood in the snow’; these poems tune their gaze to those evidences of atrocity before the snow melts or is washed away. Sometimes, Mort’s poems are shovels, excavating the slippery surfaces of memory. What do they dig up? Mostly bones:

12

Put your bones into braids of graves, woods.

Put your bones into braids of graves, ravines.

Put your bones into braids of graves, fields.

Put your bones into braids of graves, swamps.Put your graves into braids of bones, mother.

Put your graves into braids of bones, moth.

Put your graves into braids of bones, ghost.

Put your graves into braids of bones, guest.Braid your bones neatly.

Braid your bones bravely.

Finger-comb your bones

into neat braids

in our woods, ravines, fields, swamps.(‘An Attempt at Genealogy’)

This excerpt offers an argument for the book: death pervades everything, flora and fauna alike, nothing is safe from the traumatic fallout of human conflict, where that conflict is often patterned through history, not unlike the musicality of Mort’s poems. This conflict is heightened by the anaphoric, almost-lullaby, melody Mort insists upon in her repetition of ‘Put your graves into braids of bones’. The rising feet of two anapests and an iamb create a bouncy, cheerful rhythm that sonically argues with the macabre subjects of grave burials and the ghosts that inhabit these landscapes. The inscription of bones to non-animal entities (‘woods, ravines, fields, swamps’) yokes a physicality to these entities, and if they are physical, then they too, possess the capacity for a type of bodily memory. A distinction is made when asking ‘mother, moth, ghost, guest’ to ‘[p]ut [their] graves into braids of bones’ – there is a hauntological and resurrective impulse behind this inverse construction. The deaths of landscapes and resurrections of beings, here, reinforces the various strata of life-force Mort is considering.

In other sections, whole phrases return with ghoulish similarity, braided into the text, and we come to understand the function of the excavated ‘bone … a key to [the speaker’s] motherland’:

6.

In a village known for a large puddle

where all children fall between two categories

of those who hurt living things

and those who hurt nonliving things,

[…]

an alphabet on gravestones,

marble letters under the moth-eaten snow.

Under the moth-eaten snow

my motherland has good bones.

7.

My motherland rattles its bone-keys.

A bone is a key to my motherland.

8.

My motherland rattles its bone-keys.

Eve watches with her one red eyelash.Under the moth-eaten snow

my motherland has good bones.

Are these images surreal or real? Manifestations of dreams? Surrealism, in this collection is not merely clever visual escape; it seems to be the only way in which Mort might best represent three different worlds – concomitantly, three different relations to time – colliding: the world of the dead (‘bone-keys’), the resurrections of the dead (‘rattles’, ‘watches’), and the present in which they are all unified, exemplified by the forward momentum through time that poetry, in its reading, substantiates. Mort, in in a conversation with Carloyn Forche, says it would be too difficult to discuss the realities of war, genocide, poverty, hunger in Belarus, in any other way. So, in Mort’s perception, ‘cars’ must ‘resemble giant turtles shells’, the speaker’s ‘ophthalmic distortion’ must result from ‘ants on [their] eyeballs’ (‘Rose Pandemic’).

It’s a visceral, horrifying image – ants (the plural is important) crawling across an eyeball. Yet, horror is not the single sentiment these poems transmute. Subjects are always dichotomous. Simultaneously they encase the trauma of experience while also boldly displaying fascination; by fascination I most nearly mean a fastening to. Mort seems fastened to these subjects, such that the musicality of the poems is at once the tether and cleave, is at once dread and wonder, as in ‘Music Practice’:

In the intermission between

two wars

your father sang a song.

By the time

I heard this song, it had no music.

And later:

I was drafted into music.

Mort diffracts music’s necessity. Music, however delightful Mort’s idiosyncratic and aural compositions may sound to the ear, is not a choice, but a mode of survival:

Music which, over accordion keys,

unclenches the fist of ancestry,

loosens fingers into rose petals.

(‘Rose Pandemic)

Elegance – strict control masquerading as simplicity – is not this collection’s raison-d’être. In fact, the collection is aware of its own faux pas: whether it’s embarrassment rising from loud hotel sex (‘Poet’s Biography’), or a basking in the negligible problems youth can make seem large. In ‘Baba Bronya’, a young speaker recounts moments with her ‘grandmother’s aunt’, who, unbeknownst to the speaker, lived with her family for seven years. The speaker ‘complain[s] about having to go to school’ and wearing ‘unfashionable clothes’ whilst Baba Bronya, a living relic of wartime, recounts moments of ‘hunger, bombing, exile, sickness or death’. When Aunt Bronya dies, the speaker ‘quit[s] studying music.’ And here, Mort poses another relation between music and the body. Baba Bronya’s body is replaced by a ‘small stack of yellowed photographs’. One could say, that because Baba Bronya disappeared, the musical practice that accompanied her life, too, must disappear.

Mort has already told us ‘touch … is music’ (‘Rose Pandemic’). So why not the inverse? Music is touch. I’m thinking about how when there is a wound or scar on the body, the hands, against the mind’s will, try to rub it, soothe it, though this may or may not actually accelerate the healing process. Music for the Dead and Resurrected, however morbid the image, is Mort musically, touching a war-torn country. It is this compulsion towards music (as opposed towards re-presentation) that makes the poems, rather than about events, events themselves. Mort successfully argues that music might be the only way in which we can touch across past, present, and future.

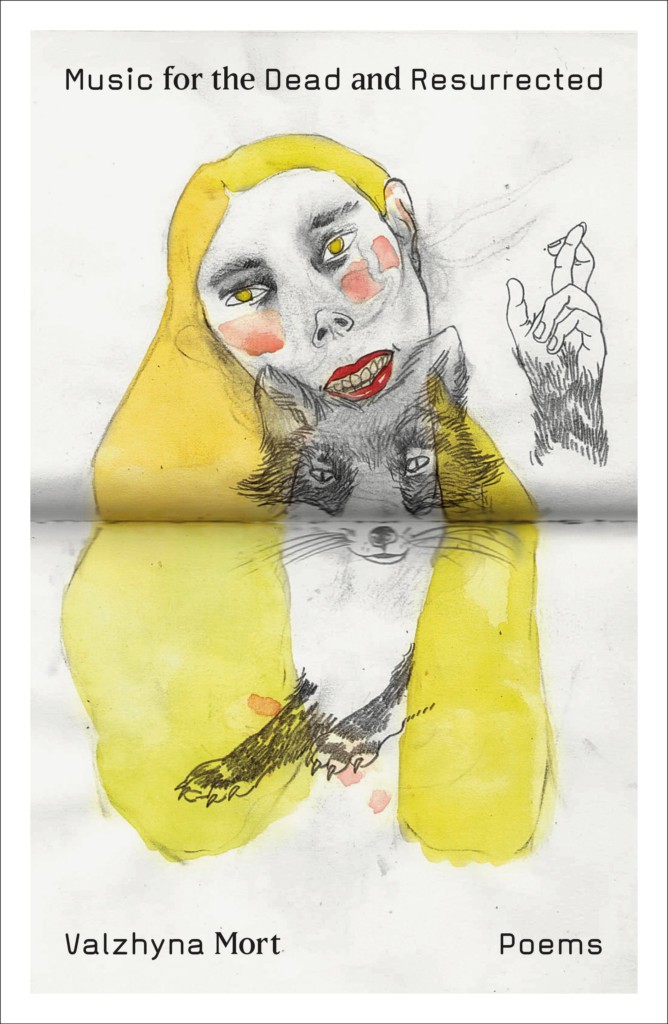

Music for the Dead and Resurrected by Valzhyna Mort

You can buy the book here

Oluwaseun Olayiwola is poet, critic, choreographer, and dancer living in London. His reviews have appeared in the Telegraph, the TLS, and Magma.

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.