‘Home’ is a contentious word. Both personal and political, ‘home’ implies belonging, and not belonging.

In Robert Frost’s ‘Death of the Hired Man’, ‘Home is the place where, when you have to go there, / They have to take you in’. But is that place where we live, where we were born, where our family is from, or where we raise our own family? Is it the country(ies) whose passport we hold? In Jennifer Wong’s Letters Home, home is a shifting concept, suspended between places, pasts, cultures, and potential futures:

Neither do I

know after all these years

if I am a Chinese girl who

wanted to go home

or a woman from Hong Kong

who will stay in England.

(‘Of butterflies’)

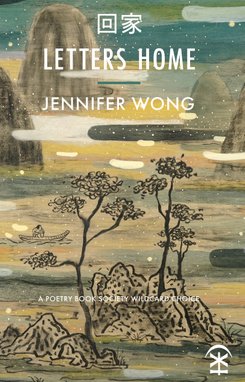

In the PBS Spring Bulletin, where Letters Home is a Wild Card Choice, Wong says the Chinese book title means ‘returning’ home. Instead of writing to home from a distance, as the English title implies, the Chinese presents the speaker in motion towards home. This drives the narrative of the book. We are vividly presented with the story of Wong’s migration from her native Hong Kong to England, but also constantly considering her draw back ‘home’.

Letters Home is a formally dextrous collection, consisting of contemporary lyric poems, prose poems, as well as multilingual poems (with a helpful gloss at the back). Few poems are actually presented as letters (epistolary poems), but the concept of letter writing pervades – a desire to keep the lines of communication open, helping ease the pain of separation. The concept of ‘letters’ as in the Roman alphabet (English) versus (Chinese) logograms is also in play, as Chinese characters thread throughout the text. What is lost between languages and versions of the self is eloquently evoked:

If one day you look for

my childhood, you will find

it lies elsewhere, in a country

with no alphabet …

(‘Daughter’)

Wong knows the idea(l) of home is complex, and resists romanticising the past. She describes the sense of dislocation manifest in the power structures of Hong Kong: ‘the British // lived on mid-levels like paradise birds / and the Chinese sweated, selling meats’ (‘King of Kowloon’). Also, how language is hierarchical: ‘Some of us stammer in our own tongue – / it’s inferior, we know it’ (‘Diocesan Girls School, 1990-1997’). And how taught identity clashes with emotional identity: ‘We sing English hymns from the blue book, / as if those songs were our own’ (‘Diocesan Girls School’). The result is a conflicted sense of self at the outset: ‘me, who never had a proper country to start with’ (‘Girls from my class’); ‘家is home, or family, or none of those’ (‘Ba Jin (1904-2005)’).

The theme of transformation recurs, often in the form of butterflies (the Monarch butterfly also famously migrates large distances). Flight is a necessity: ‘We dream of going away / to England or America, / and never, never coming back’ (‘Diocesan Girls School, 1990-1997’); ‘to pin down my ancestry wasn’t / half as important as learning how to fly’ (‘Anser anser’).

When the time comes to leave home, facets of the self are hidden in the accompanying baggage: ‘I did not tell anyone that I had / a ricecooker in my suitcase’ (‘Arrival’). The long central poem ‘Mountain City’ recounts Wong’s relocation in moving detail, with formal control. She invokes Eliot: ‘April is a nostalgic month.’ The new place is alien at first: ‘What do they mean, a few years / of feeling foreign’ (‘Mountain City’) and ‘they put / all the foreign students together / so they’d feel more at home (‘Arrival’). Over time a form of assimilation is possible, but always limited: ‘“Home,” I said / but it hurt’ (‘Arrival’); ‘I, an immigrant, am tired of speaking / and listening in their tongue’ (‘London, 2008’).

Even motherhood, a transformative experience that sees a new generation born in England, turns the speaker towards and away from ‘home’: ‘In a house spiced with memories / I indulge in my tribal ways’; ‘Baby daughter, get ready for England!’ (‘Postpartum vinegar’).

Wong sometimes adds dates to poems to help us follow the narrative clearly. But she also cuts across this to highlight actual time versus lived time: ‘It’s British summer time / in my living room // but my watch in the drawer / moves seven hours ahead’ (‘Of butterflies’). Cultural constructs of time are also explored; in ‘An engraved Chinese teapot’, a friend comments that Chinese tenses ‘have so much emphasis on history it’s hard to realise the present needs a life of its own’. It calls to mind the Maori saying of ‘walking backwards into the future’. There is a sense of waiting for the present to happen.

Yet even the past is changing. The foundations of Wong’s native Hong Kong are seismically shifting: ‘fragments /of a changing city’ (‘Mountain City’); ‘the textbooks for our children / are changing’ (‘Metamorphosis’). Compare Larkin’s ‘Home is so sad. It stays as it was left, / Shaped to the comfort of the last to go’ to Wong’s ‘I wonder how a city / can outgrow the country, / if going home is still an option’ (‘Metamorphosis’). Larkin’s ‘home’ is a static place that, emptied of you, lies bereft and awaiting your return. There is an immense complacency to his tone. But fundamental changes to governance and culture in Hong Kong leave Wong ‘follow[ing] news on the protests over there, / night after night’ (‘Trace’), prompting a friend to say ‘don’t torture yourself’ (‘Truths 2.0’). When she meets an old colleague who ‘never left our people’, she muses ‘you are still confident about our city’s / future, despite’. The poem ends there, with no full stop, as if the speaker can’t bring themselves to complete the sentence.

The lyric I in the poems presents as trustworthy, as attempting to tell ‘the truth’. But the I questions its own versions of itself: ‘to question that historical self years later’ (‘Letter to AS (T)7’). There is an acute awareness that the current self replaces possible others:

And the years

I have lived here, have cost me

all those places I once tried to

leave from, am leaving still,

places that are so real

even if they remain invisible …

(‘From Beckenham to Tsim Sha Tsui’)

One possible solution is to ground the self metaphorically and geographically: ‘More than anything or any poem, we wanted to buy a house’ (‘Real life thesis’). In Emily Dickinson’s ‘The Props assist the House (729)’, when ‘the House is built […] The House support [sic] itself / And cease [sic] to recollect’. Yet the final section of Letters Home is called ‘remember to forget’ – as if forgetting requires conscious action. And that action is, at best, partially desired: ‘To tame the water dragon / is as impossible as learning to live with it’ (‘Yangtze’).

For Wong, remembering is an act of commemoration and keeping contact with her (other) home. Although it is ‘An almost-past life now’ (‘At the wet market’), it is not ‘past’. The collection ends: ‘each year I think of going back because of the soup’ (‘Personal history of soup’). We are back at the beginning with the book’s title, with the speaker in motion towards home.

Letters Home is an accomplished and enlightening collection that resists easy answers to questions of identity, geography, and belonging that affect us all.

Buy Letters Home by Jennifer Wong from the Poetry Book Society website.

If you’d like to review for the Poetry School, or submit a publication for review, please contact Sarala Estruch on [email protected] or Chloë Hasti on [email protected].

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.