We are delighted to share our favourite poetry books of the year!

It has been another challenging year for obvious reasons, but, in spite of it all, poetry has not only persevered but thrived! 2021 has seen the publication of so many incredible titles, both from established names and emerging poets.

So, without further ado, here is a list of the books that we, at Poetry School, loved discovering and spending time with this year. We hope you enjoy reading this list (presented in no particular order) and maybe even find some Christmas gifts for friends and loved ones!

(Please note: The works listed below are all our Poetry Books of the Year 2021. Those of us with the time have had the great pleasure of writing short reviews of some of the books. Titles on the list without a review are just as valued as those without.)

Comic Timing weaves through the beauty and blunt pain of womanhood, work, and life.

A number of the poems engage with ‘Rent’; they’re strewn with ‘contracts’ and ‘commutes’. Pester uses repetition to illustrate these points and to reproduce the monotony of work, only to be granted what should be our birth-rite: a place to live: ‘I am stupid for getting into debt paying rent’.

The collection also battles with the female body, the title poem ‘Comic Timing’ chronicling an abortion. The speaker highlights how normal her day is: she takes an Uber, eats a ready meal, interacts with a housemate. The poem is littered with the commonplace, and this makes the brutality of her experience sing louder: ‘still bleeding / a bit still on the brink’. And in ‘Historical Bed Sores’ it’s bemoaned that women are still muzzled by the pressure to have children: ‘without babies we chirp into caves’.

Throughout, this book finds ways to show us the extraordinary as we tread the everyday. Pester’s poems are full of mother’s craving cakes made of blood, or men with chests that are ‘like a TV’. The speaker is urged to flip the commonplace and make it absurd. What results is a twisted lullaby of modern life – it will make you look upon your own sense of normality with a fresh gaze.

– Jasmine Ward, Ginkgo Prize Manager

This Fruiting Body is an explosion of sexuality and nature – it is a battle cry for an earth that is wilting, yet, in its demise, perishes in a glittery dress.

Given the state of the planet, poetry about it can be depressing. Yet hope pulses through this collection which celebrates cities and people and mess, as much as it laments the destruction they create. Ecopoetry can be dour, and a love of nature is often associated with poor hygiene and Birkenstocks. Yet these poems show us that earth lovers can be loud and dazzling, covered in phosphorescent silk.

The book is imbued with important messages. In ‘I swallow’, Parkin demonstrates how everything is connected: our plastic bags, fake eyelashes, hopes and dreams all run through the veins of this planet. He shows us what is queer and extraordinary about mother nature. Wedding queerness to the earth is a political statement, as he reclaims childhood stories and myth. In ‘Shrinking Violets’, Parkin reimagines a scene from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, the one where Violet Beauregard explodes. Except, in Parkin’s iteration, it’s a young queer boy, and when he explodes it is fantastic, empowering, the opposite of the ‘shrinking’ expected of him. ‘My unyielding presence / my un-ruly second-on-second growth’.

But the writing is this book’s greatest feat – strip it of its messages and what remains is a luminous voice, fabulous and idiosyncratic.

– Jasmine Ward, Ginkgo Prize Manager

I met Alice Hiller the first month I started working at Poetry School. We hosted a class for new students, open to all, and Alice came as the School’s graduate to present some of her work. There, she read ‘elegy for an eight year old’. I had never been so physically and tangibly affected by a piece of writing before. The poem was – is – painful, horrifying, violent, and crafted to perfection. I have been waiting for bird of winter since that day in 2018.

Alice’s debut collection, interweaving her childhood memories, adolescent medical notes, and excavating the city of Pompeii, is a courageous, powerful, and beautiful literary account of trauma that might seem insurmountable. The journey that Hiller portrays on the pages of her collection has a trembling force; it is so powerful, so clear, and so incredibly empowering to survivors of abuse to see the path towards healing: ‘open sky and water / wind-blink a clear pool / of june silver rushing / her skin with spangled rings of joy’.

– Maria Lewandowska, former Poetry School team member

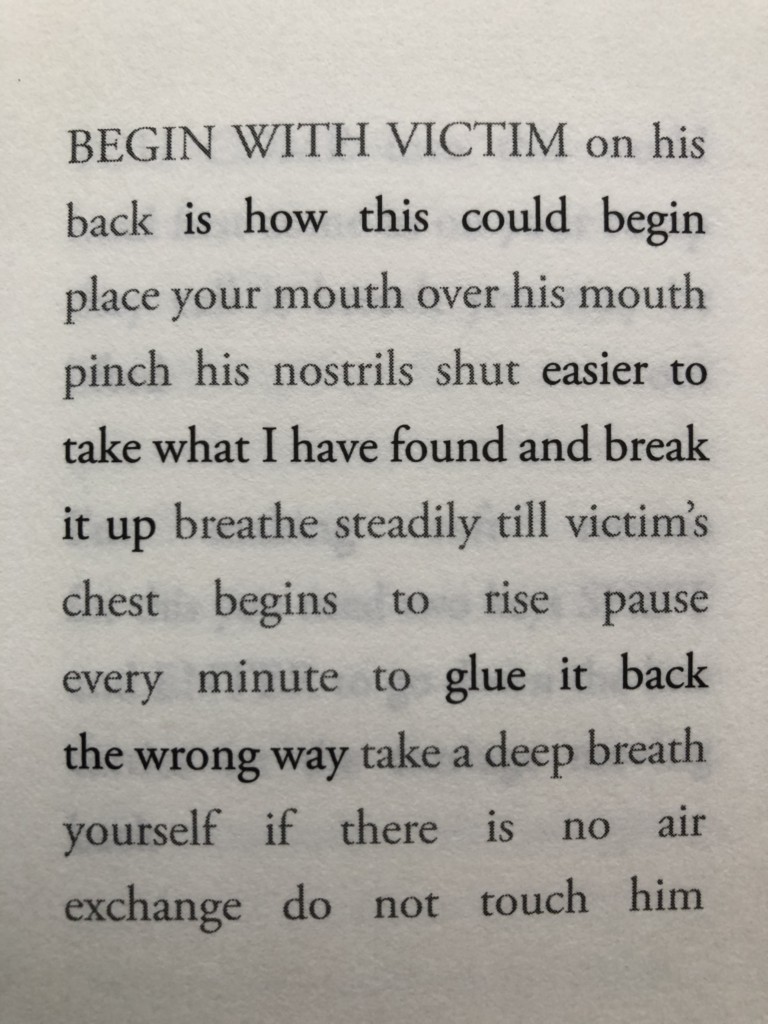

Gail McConnell’s debut full-length collection, The Sun is Open (Penned in the Margins), explores her father’s murder in Belfast in 1984 by the IRA; William McConnell was shot outside his house, in front of his wife and daughter (the poet, at three years old). The subject matter is harrowing but it is McConnell’s handling of the subject that makes this book such an arresting and revelatory read.

The poems are presented as double justified prose blocks, which look like newspaper articles and also bring to mind the ‘Dad Box’, the container in which the poet stored various documents relating to her father, and which she drew from to write the book. These prose poems often incorporate found material from the ‘Dad Box’, creating a collage effect as the poet attempts to piece together the story of her father’s life and death, while remaining questioning and self-aware:

Other poems are more preoccupied with memory and recreating the world of the three-year-old child who lost her father; the writing moves deftly from adult voice to child voice; from present to past: ‘I’m only small I’ve cherry lips / hard gums milk teeth / red chocolate hearts in our / mouths’.

The absence of punctuation throughout the collection makes the reader work harder to decipher the intended meaning of each – frequently enjambed – line, which mimics both the child’s relationship with language and meaning (as something to be puzzled at and teased out) and the poet’s attempt to make sense of the materials she is working with: language (found text/created text; written language/spoken language) and memory (first-hand, second-hand, and imagined).

The Sun is Open stretches and interrogates the limits of language and memory to create a work which is engaging, affecting, and bristling with life.

– Sarala Estruch, MA and Editorial Manager

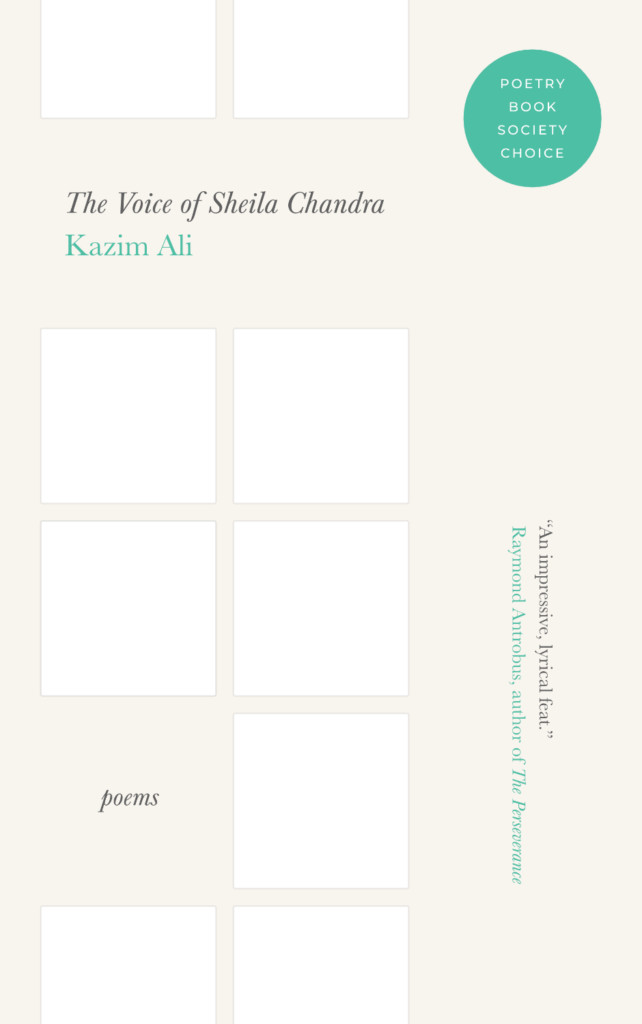

Kazim Ali’s The Voice of Sheila Chandra is a hybrid text which radically expands our notions of what a poem – or a poetry collection – can and should be. In this exciting, vibrant and expansive work, Ali asks: what is history? What are the limits of language, of music, of poetry, or the human mind? The text constantly pushes against perceived limitations.

The collection consists of three long poems interspersed with four shorter poems, which act as intermissions or ‘breathers’ between the long pieces, while in themselves being fascinating and original poems, which lean into many of the themes explored in the longer poems.

The first long poem, ‘Hesperine for David Berger’, is written in a form Ali invented while writing the poem. The hesperine weaves together different stories and strands of thought – musings on history, physics, music, spirituality – and creates a tapestry of multiple possible meanings. These separate threads shift from fact to abstraction, and include real and imagined histories. One of the central questions the poem asks is whether or not the past can be changed by reimagining it:

Can history be unwoven the tightness released to make it possible to breathe and write anew

‘Phosphorus’ is an expansive poem, which explores themes such as: city life, nomadism, friendship, desire, love, and loneliness. Written in cinquains interspersed with word grids or constellations of alphabetical letters which directly challenge the reader’s ability to decode language, the poem made me feel both unmoored and excited at the multiple possible meanings that I may or may not have been decoding correctly.

The titular poem, ‘The Voice of Sheila Chandra’, is a sonic experimentation in 40 sonnets in which the relationships between language, music, and meaning are explored both thematically and through the language of the poem. In this piece, rhythm and sound often take precedence over sense:

She merged with the vibe

Ration of the drum a hum a

Home womb and um

She OM moaned in the loam

The poet is trying to grasp ‘what language cannot / Hold onto what you cannot / Hold onto’, attempting to ‘transcribe what flickers what is not / Fixed’, while, at the same time, acknowledging the impossibility of the task. The beauty and power of the poem (and the collection as a whole) is, of course, in the trying.

– Sarala Estruch, MA and Editorial Manager

Jason Allen-Paisant’s Thinking with Trees is elegant and challenging, especially (as a dog lover) the way it takes on dogs and the ways they take up space in parks and outdoor locations.

– Caleb Parkin, MA Personal Tutor and Poetry School Wellbeing Adviser

Add your Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.